Architects

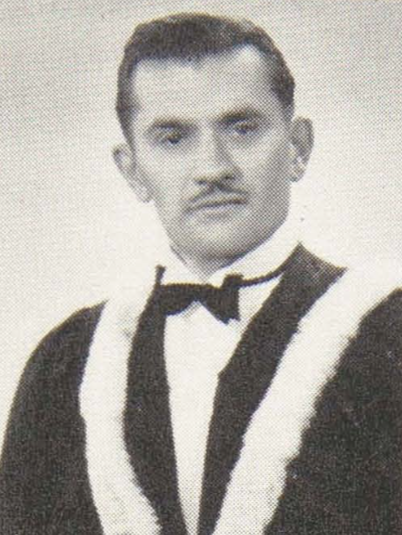

Nikola Zunic

- 1921–2006

- MAA

Biography

Born April 12, 1921 in Prilisce Dolnje, Croatia, Nikola Zunic immigrated to Canada with his family in May 1933. In Winnipeg, following graduation from St. John's Technical High School, Zunic attended the University of Manitoba, beginning his studies with the Faculty of Arts and Science in September 1939. He temporarily abandoned his university education in 1942 and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force’s Second World War effort; amongst other positions, he served as a navigator and flight officer with the 419th Squadron. Upon his return from the war, Zunic resumed studies at the University of Manitoba and graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture in May 1950.

In a later profile, Zunic said that it was, in part, witnessing the destruction of the war that convinced him he wanted to build things. (Gloria Taylor, “Zunic a major player in design of south Winnipeg” Winnipeg Free Press Weekly, October 7, 1990)

Not long after graduation, Zunic obtained a position at the University of Manitoba’s Planning Research Centre, where he worked until 1952. In the same year, he registered with the Manitoba Association of Architects. Shortly thereafter the young architect established an independent practice with offices on the second floor of the Canadian Bank of Commerce building at the corner of Rue Marion and Avenue Taché (119 Rue Marion, originally a branch of the Bank of Hamilton, 1910) in Winnipeg’s St. Boniface neighbourhood, then a separate city. A large number of Zunic’s projects would be built in this area. In 1958, Zunic served as a director of the St. Boniface fiftieth anniversary jubilee.

Important early commissions included the design of a 12-classroom school in St. Pierre-Jolys, Manitoba. The Canadian Legion Gardens was another significant project during the 1950s (675 Talbot Avenue, Winnipeg, 1956). This development for low-income seniors – a series of small, clean-lined duplex cottages in a park-like setting – was built with the aid of the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Legion members on city-donated land.

From this period onward, Zunic worked as an architect, developer and builder. As a designer, Zunic often practised a tempered form of modernism that remained open to local conditions and alternative functions. Perhaps his largest project, a 1956 subdivision of 156 homes in Niakwa Park, reveals this bent. Here, Zunic and his partners deliberately sought to build around and save many existing trees, even building sidewalks around them. At the same time, the architect also attempted at Niakwa Park to engender a certain diversity in design, stating: “it was our plan that we wouldn't set up the houses like soldiers.” (Taylor, “Zunic,” 1990) Beyond homes, Zunic’s company here also developed streets, schools, and libraries.

Such a diversity of types is also evident in Zunic’s other work. These included more than 35 schools throughout the province and a large number of churches. Amongst these is the angular St. Alphonsus Catholic Church (341 Munroe Avenue, Winnipeg, 1958), built with Zunic’s partner from this time forward, Victor Sobkowich. Another notable church by Zunic is Holy Family Ukrainian Catholic Church (1001 Grant Avenue, Winnipeg, 1963), the result of a partnership between Zunic, Sobkowich and Radoslav Zuk. Here Zunic combined an expressive modernist design with traditional symbolism; the three towers representative of the Holy family and the seven rounded arches personifying the seven tribes of Israel. Amongst other projects, Zunic also designed the simple masonry Happyland Park Swimming Pool (520 Marion Avenue, Winnipeg, 1962) and the St. James Civic Centre (2055 Ness Avenue, Winnipeg, 1966). Later projects included the 10-storey Foyer Vincent retirement residence (200 Rue Horace, Winnipeg, 1970), the addition of a new wing with gymnasium, library, science labs, open area classrooms and a multi-purpose room to L'Ecole du Precieux-Sang (209 Kenny Street, Winnipeg, 1972) and a 1972 retirement residence in Gretna, Manitoba.

Beyond his architectural practice, Zunic served on the executive of the Manitoba Association of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. He served as an executive on the Canadian Chamber of Commerce from 1957, and as a provincial representative, beginning in 1965. Beginning in the 1960s, Zunic was twice elected as a board member of the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation, a prominent federal housing agency. In this capacity and elsewhere, he argued in favour of more creative design for new home construction and against the conservatism of zoning rules and mortgage funds.

Projects

- 101 Champlain Street, 1954

- Park Lawn Funeral Home, 1858 Portage Avenue, 1955

- 8 Mohawk Bay, 1955

- 19 Mohawk Bay, 1956

- 31 Iroquois Bay, 1956

- Frontenac School, 866 Autumnwood Drive, 1956

- St. Alphonsus Catholic Church, 341 Munroe Avenue, 1958

- Windsor Park Library, 955 Cottonwood Road, 1961

- Happyland Park Swimming Pool, 520 Marion Avenue, 1962

- Holy Family Ukrainian Catholic Church, 1001 Grant Avenue, 1963

- Transcona Police & Fire Hall, 730 Pandora Avenue West, 1966

- St. James Civic Centre, 2055 Ness Avenue, 1966

- 117 Clearwater Road, 1967

- Foyer Vincent, 200 rue Horace, 1970

Sources

- “Architect Says Mortgage Funds Lack Imagination.” Winnipeg Free Press. 25 September 1965.

- “C Of C Names Manitobans.” Winnipeg Free Press. 3 October 1957.

- “Engineering Graduate Class Biggest In U History.” Winnipeg Free Press. 17 May 1950.

- “Join the Fight Against Cancer: Visit the Beautiful Bungalow.” Winnipeg Free Press. 24 September 1954.

- “Legion Gets Green Light on Housing.” Winnipeg Free Press. 17 August 1956.

- “Nikola Zunic: Obituary.” Winnipeg Free Press. 15 April 2006

- “School Wing Opening.” Winnipeg Free Press. 19 October 1972.

- “St. Boniface Home For Elderly Okayed.” Winnipeg Free Press. 30 August 1969.

- “Transcona To Vote On Hall.” Winnipeg Free Press. 21 May 1965.

- Ukrainian Churches of Manitoba: a building inventory. Winnipeg: Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Historic Resources, 1987.

- Graham, John W. Guide to the architecture of Greater Winnipeg. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1960.

- Keshavjee, Serena. ed. Winnipeg Modern. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2006.

- Kowcz-Baran, A.M. Ukrainian Catholic Churches of Winnipeg Archeparchy. Winnipeg: Archeparchy of Winnipeg, 1991.

- Rotoff, Basil. Monuments to Faith: Ukrainian Churches in Manitoba. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1990.

- Taylor, Gloria. “Zunic a major player in design of south Winnipeg” Winnipeg Free Press Weekly. 7 October 1990.