Church of the Canadian Holy Martyrs

| Former Names: |

|

|---|---|

| Address: | 289 Dussault Avenue |

| Current Use: | Place of worship |

| Constructed: | 1961 |

| Other Work: | 2002 addition and renovations, Harold Funk |

| Architects: |

|

| Firms: |

|

| Engineers: |

|

| Contractors: |

|

| Interior Designers: |

|

More Information

Church of the Canadian Holy Martyrs (Église des Saints-Martyrs-Canadiens) was designed by Étienne Gaboury and completed in 1961. The design was influenced by both changes in the Catholic Church, as later reflected in the Second Vatican Council, and by the work of the European modernist architect Le Corbusier. Although predating the Second Vatican Council, the church reflects many of the changes that occurred in Canada’s post-war Catholic community. This was something Gaboury was attuned to because of his strong connection to the Catholic Church, as well as his personal relationship with St. Boniface Bishop Maurice Baudoux. Church of the Canadian Holy Martyrs can be considered an intermediate design: Modern and responsive to the changes in the church, yet not as full a realization of the aims of the Second Vatican Council as some of Gaboury’s later works. In 1964, Holy Martyrs Church was nominated for a Massey Award, the highest architectural award in Canada at that time.

In February 1961, plans were prepared for a church that would accommodate 250 people and construction was completed by December 10, 1961. The exterior was designed by Étienne Gaboury, while collaborator Bernard Aubry contributed to the interior design. Construction was contracted to Rebiffe Construction Company Ltd. Attention to small details, paired with the church’s extravagant appearance, belies its economical construction. However, exceptions were made for more costly features such as the linoleum floor, metal bench hooks, and the baptismal font. The church was dramatically altered in 2002 by architect Harold Funk.

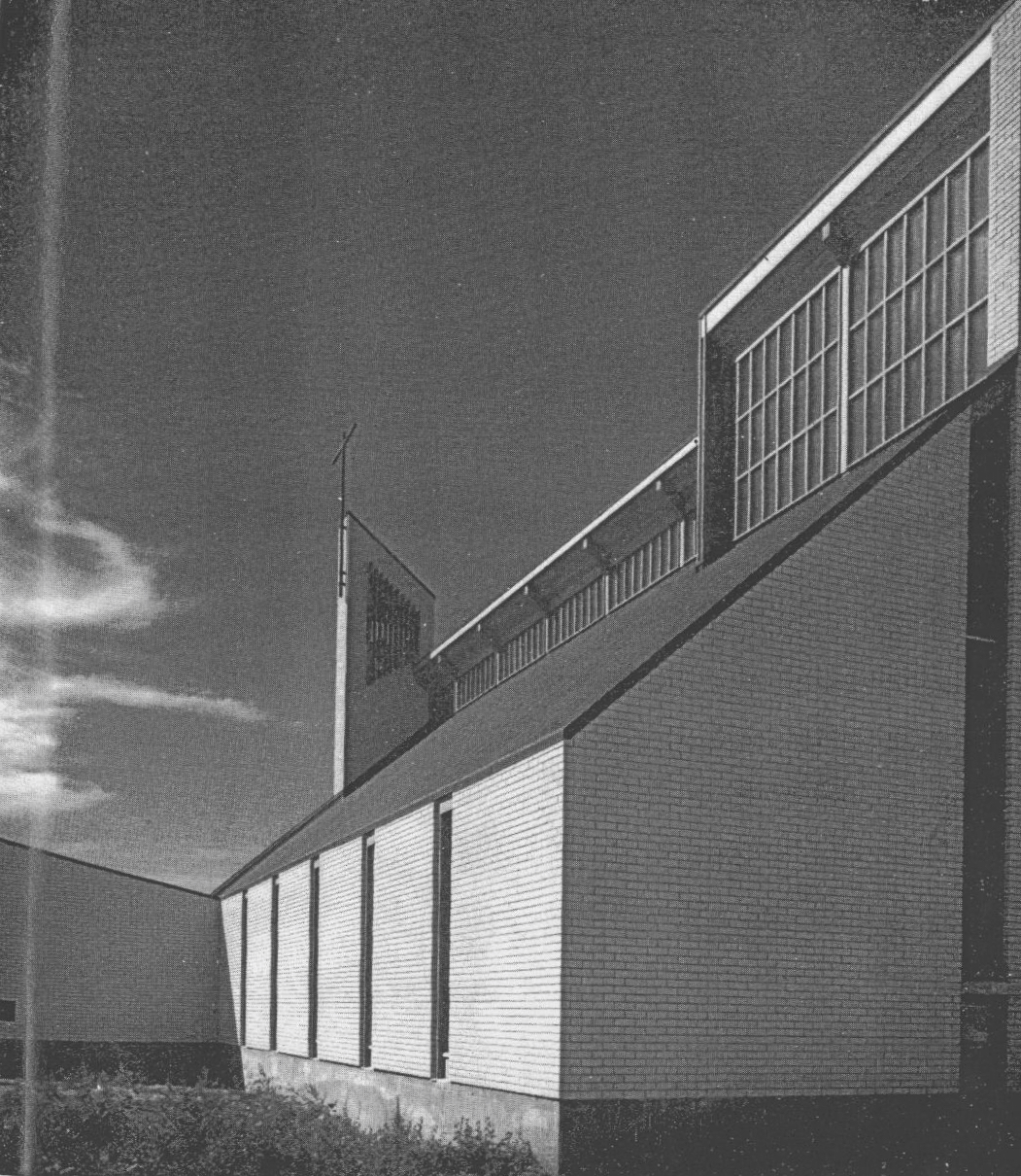

From the south side, the church has a neo-gothic A-frame, with a bell tower and cross at the centre of what would be its conventional facade. Gaboury reimagines this design, moving the main entrance from the face of the A-frame to the side, and adding many dynamic elements. Skylights are incorporated extensively on the east side, which features louvered windows that extend along the length of the building, as well as taller windows on the north-east corner. These windows have since been partially obscured by overhangs, reducing their impact somewhat. A dynamic bell tower rises along the south side of the building. It features vertical blinds, which were chosen for their form and because they would provide better acoustics for the church’s electronic bell. Consistent with the side entrance, housed in a vestibule on the south-east side, the cross atop the bell tower faces east. The vestibule was removed in 2002, although its form is still distinguishable. Opposite it on the south-west side is the baptistery, which, in accordance with tradition after the Second Vatican Council, is in the church in order to signify a parishioner’s entrance into the ecclesial community. The white exterior is accented by the originally black asphalt parking lot on either side of the building. The 2002 additions include a roofline in the form of a flat-topped pyramid with stained-glass skylight along the south-west side of the original building, as well as an extension of the wall on the same side that continues in the style of the bell tower.

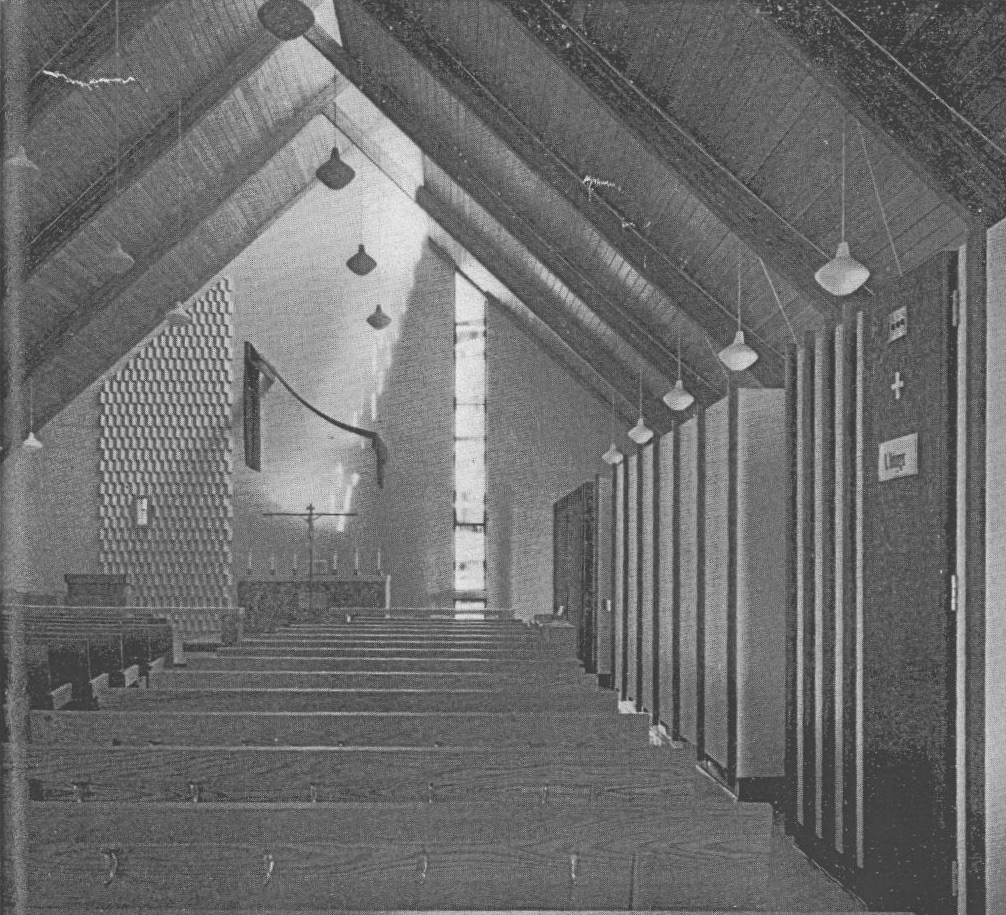

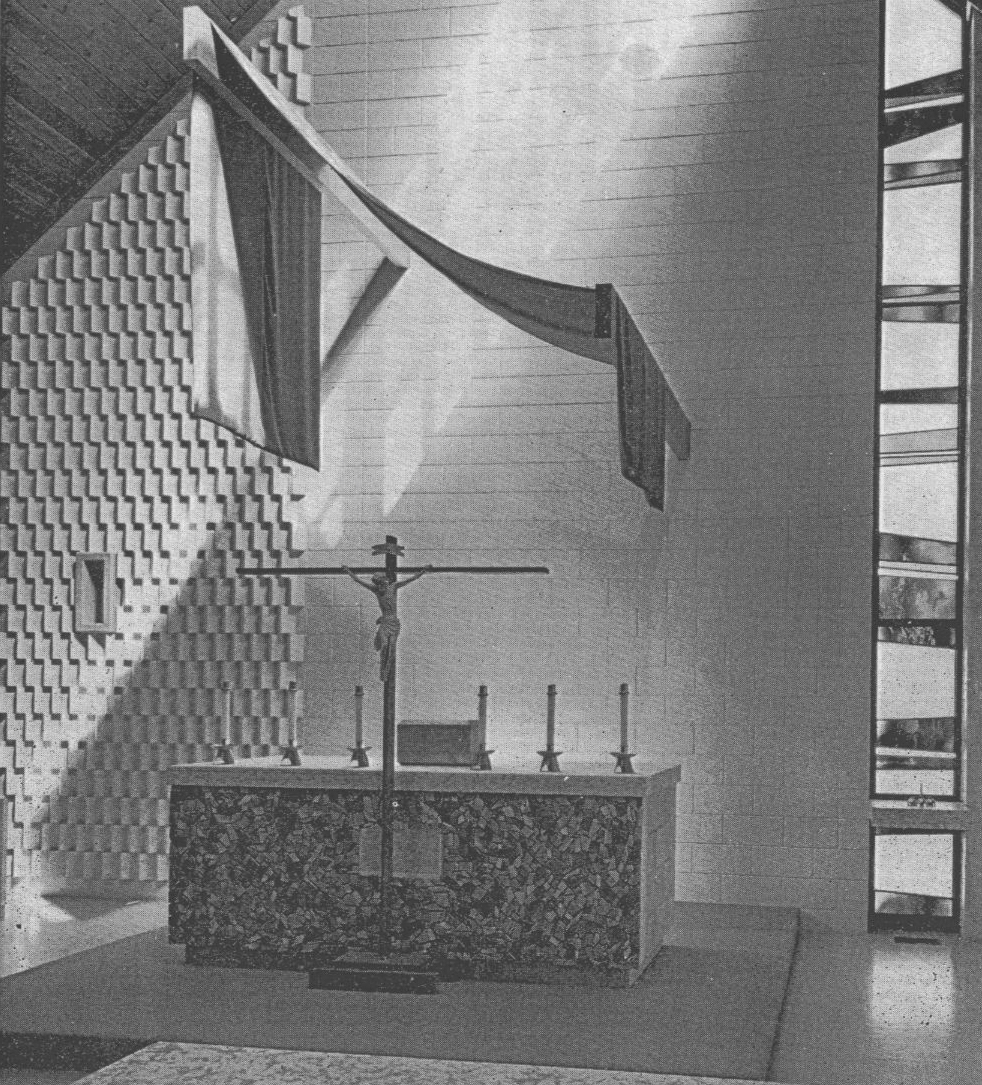

The interior is characterized by its louvered skylights that illuminate the nave, focusing light on the church’s sanctuary and honey-brick coloured altar. The interior was designed to bring parishioners closer to the church’s secondary liturgical functions, instilling a greater sense of community. Expressions of the church’s secondary liturgical functions can be found in subtle inflections within its all-encompassing space, an alternative to creating dedicated spaces. In addition, the parish hall conforms to the “versus populum” setting where the celebrant faces the congregation. The enriched wall accents the pulpit and sanctuary lamp. A cloth baldachin is used, as opposed to solid columns and canopy, which integrates elements of local culture, such as the ceinture-fléchée. The use of a cloth canopy is also modular, as it can be changed to reflect the appropriate colours of the religious occasion.

Laminated beams of oiled Douglas fir cover the interior of the roof. Rows of Scandinavian-designed light fixtures shaded with white plastic hang between the beams. The pews are birch with a walnut stain. Behind the altar is a masonry textured relief, draped canopy, and vertical glass bands that draw the eye. The altar and baptismal font are concrete coated with asymmetric pieces of glazed coloured tile that matches the rest of the church.

Design Characteristics

| Style: | Neo-Gothic |

|---|---|

| Neighbourhood: | Windsor Park |

- Neo-gothic A-frame turned sideways

- Addition of many dynamic forms, including the bell tower

- Use of skylights and natural lighting

- Modular interior spaces

Sources

“Church of the Canadian Holy Martyrs.” Canadian Architect 8 (January 1963): 34-38. (includes interior/exterior photos and plan)

Hellner, Faye. Etienne Gaboury. Saint-Boniface, Manitoba: Editions du Ble, 2005.

Matoff, Theodore. “This Bold Virile Church Fits into a Prairie Pattern.” Winnipeg Tribune. 20 March 1965.

Thompson, W. P. Architecture of Manitoba: an exhibit prepared by Professor William P. Thompson for the Manitoba Association of Architects and the Manitoba Centennial Corporation. Winnipeg: s.n., 1970.

Thompson, W. P. Winnipeg Architecture: 100 years. Winnipeg: Queenston House, 1975.

Thompson, W. P. Winnipeg Architecture. Winnipeg: Queenston House, 1982.