Buildings

Winnipeg Civic Centre (City Hall and Administration Building)

| Address: | 510 Main Street |

|---|---|

| Use: | Council Chambers and Administrative Offices |

| Original Use: | Council Chambers and Administrative Offices |

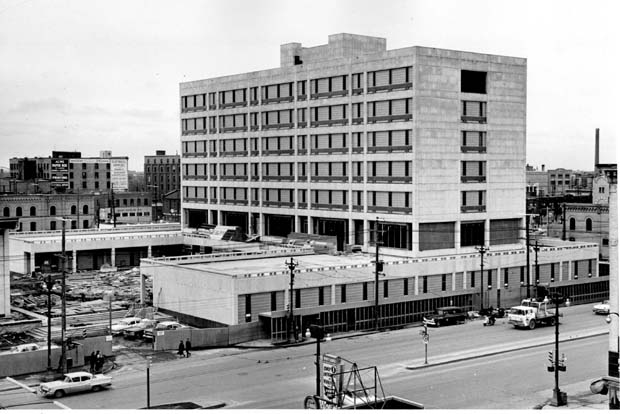

| Constructed: | 1962–63 |

| Other Work: | 1967, Construction of an underground tunnel 1968, Alterations to the Administration Building 1973, Renovations 2003, Courtyard redesign by landscape architecture firm Scatliff Miller Murray |

| Architects: | David Thordarson Bernard Brown |

| Firms: | Green Blankstein Russell |

| Contractors: | G. A. Baert Construction Limited Peter Leitch Construction (1967 tunnel addition) |

| Tours: | Part of the QR Code Tour |

More Information

In 1947 a Special Committee was established by the city to plan for a new City hall. By the mid-century, a number of factors were pushing Winnipeg toward the construction of a new building. Commentaries from the era describe the extant city hall as a “a quaint, travesty of a bygone age.” Indeed, by the fifties the population of Winnipeg had increased nearly ten-fold from 1886 levels. Furthermore, an engineers report pointed to the potential collapse and structural unviability of the old building’s clock tower, as well as issues with fire safety.

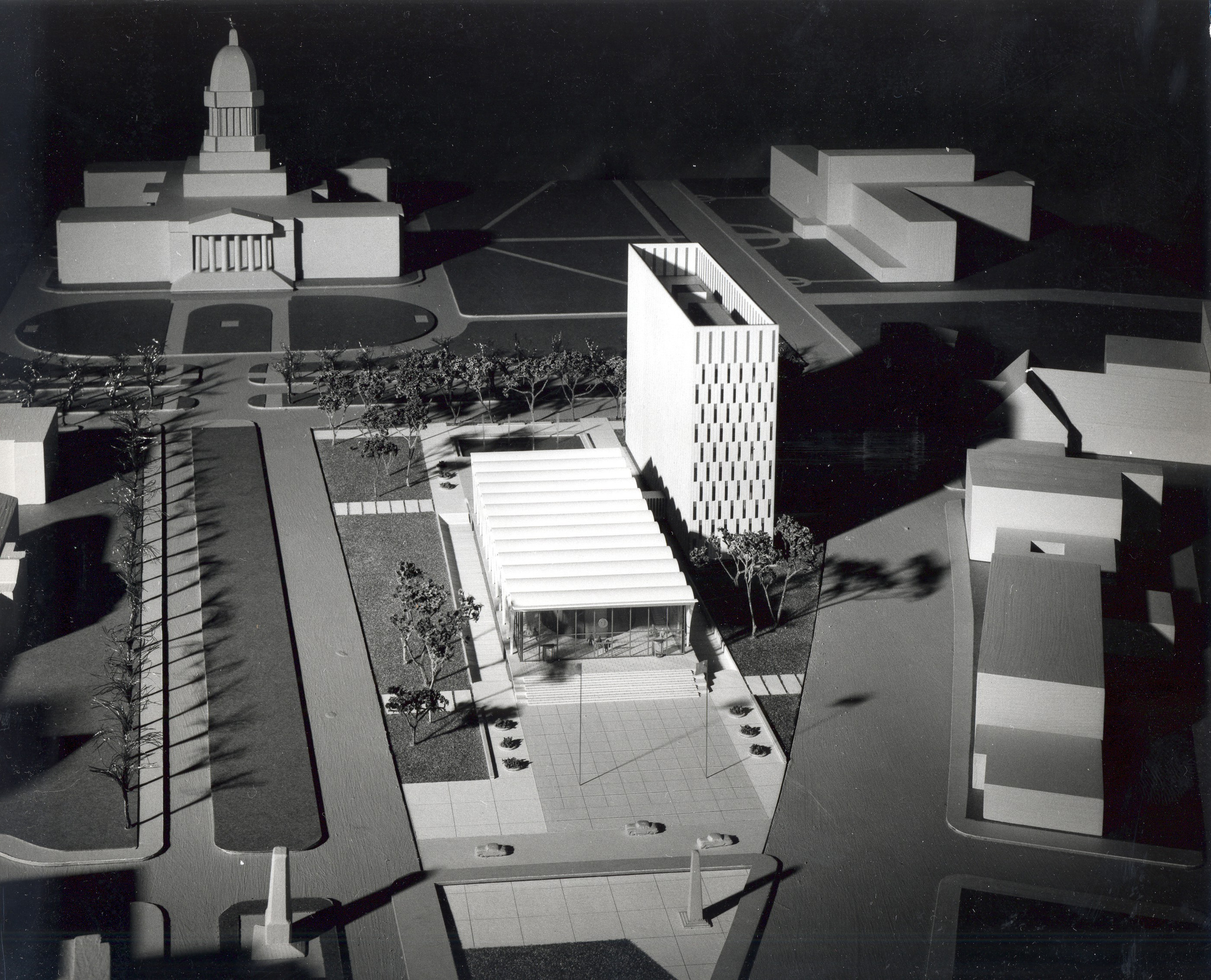

On 23 October 1957, a plurality of Winnipeg voters – 79% – cast a ballot in favour of a bylaw authorizing the spending of $6 million on a new City Hall building. This result was deemed a substantial victory for then mayor, Stephen Juba. The same plebiscite contained a companion referendum, asking citizens to chose between two possible locations for this new structure. The options presented were a site at the north-east corner of Broadway and Osborne Street North (across from the Manitoba Legislative building at the present site of Memorial Park) and the current (and historic) City Hall site, to the west of the intersection of Main Street and Market Avenue. On this measure a majority of voters – 24, 918 to 15,630 – selected the Legislature site. The two votes initiated the planning of the new building, a process which began with a national architectural competition. The judges for this contest (made public on 2 June 1958) included luminaries of the architectural world: Pietro Belluschi, Dean of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Ralph Rapson, head of the school of architecture at the University of Minnesota; Alfred Roth, Dean of Architecture at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and editor of the design journal Werk; Vancouver-based Peter M. Thornton, associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects and architect of the University of Manitoba’s St. Paul's College; and Eric W. Thrift, director of the Metropolitan Planning Commission for Greater Winnipeg. The project proved to be compelling for architects across the country and more than 210 submissions were received.

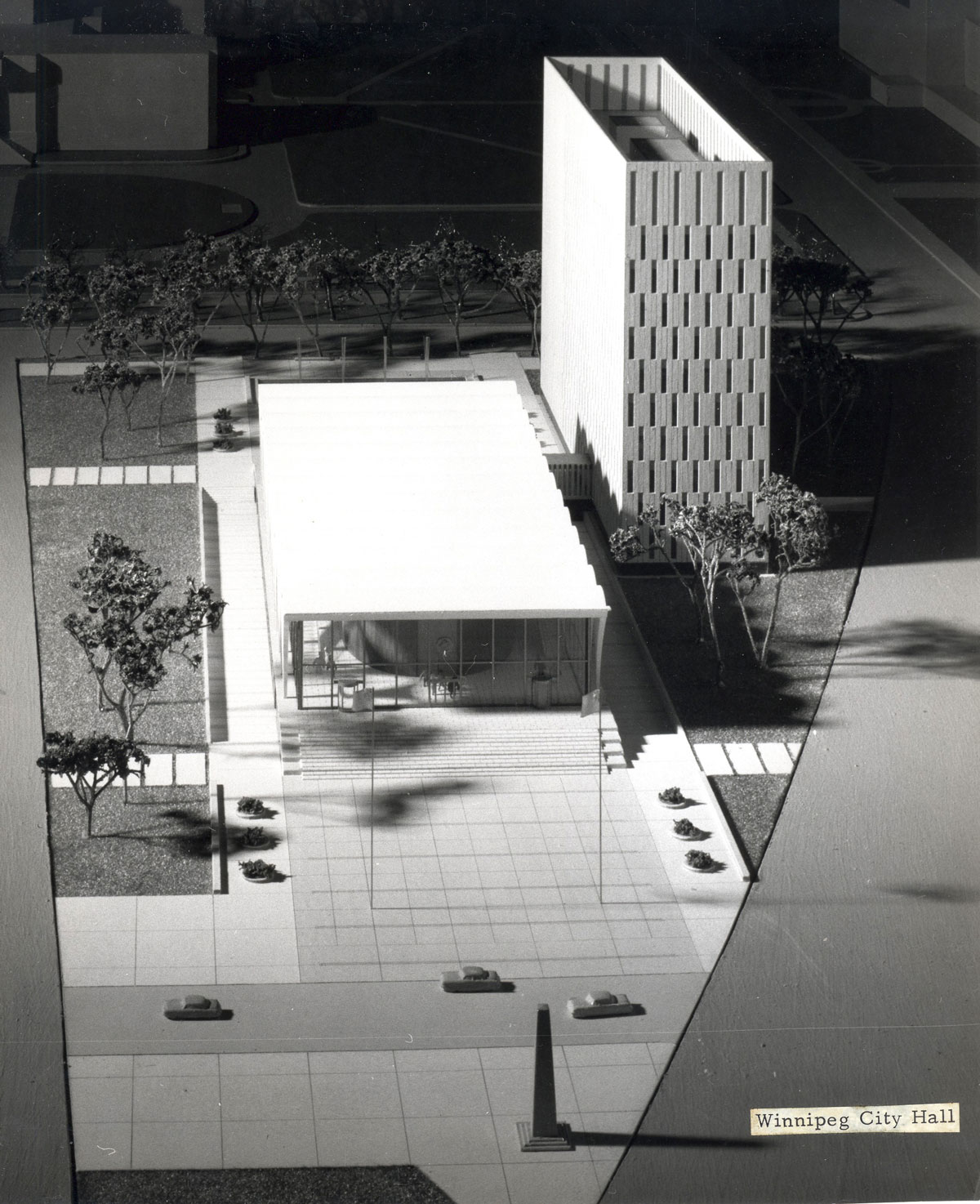

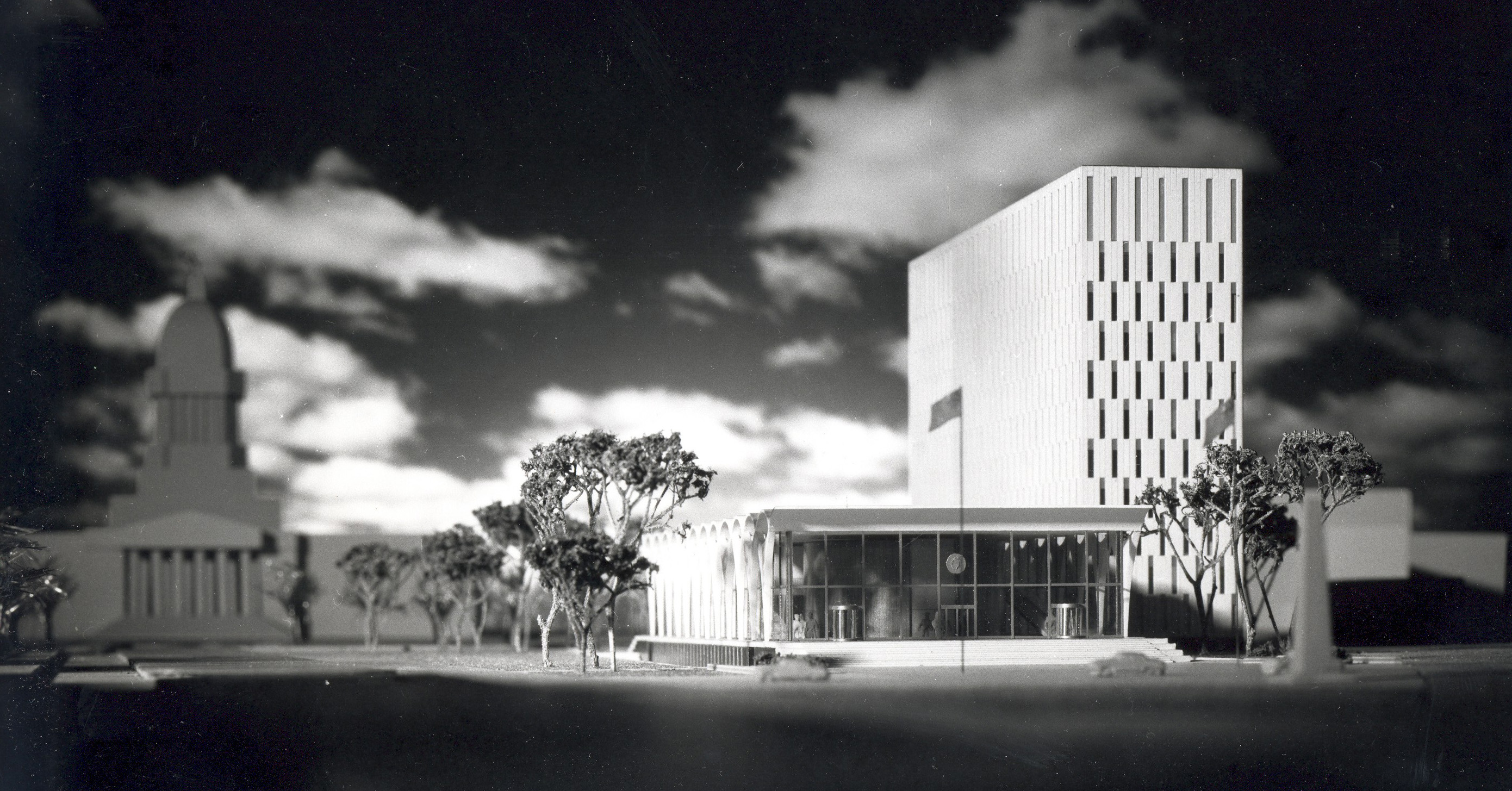

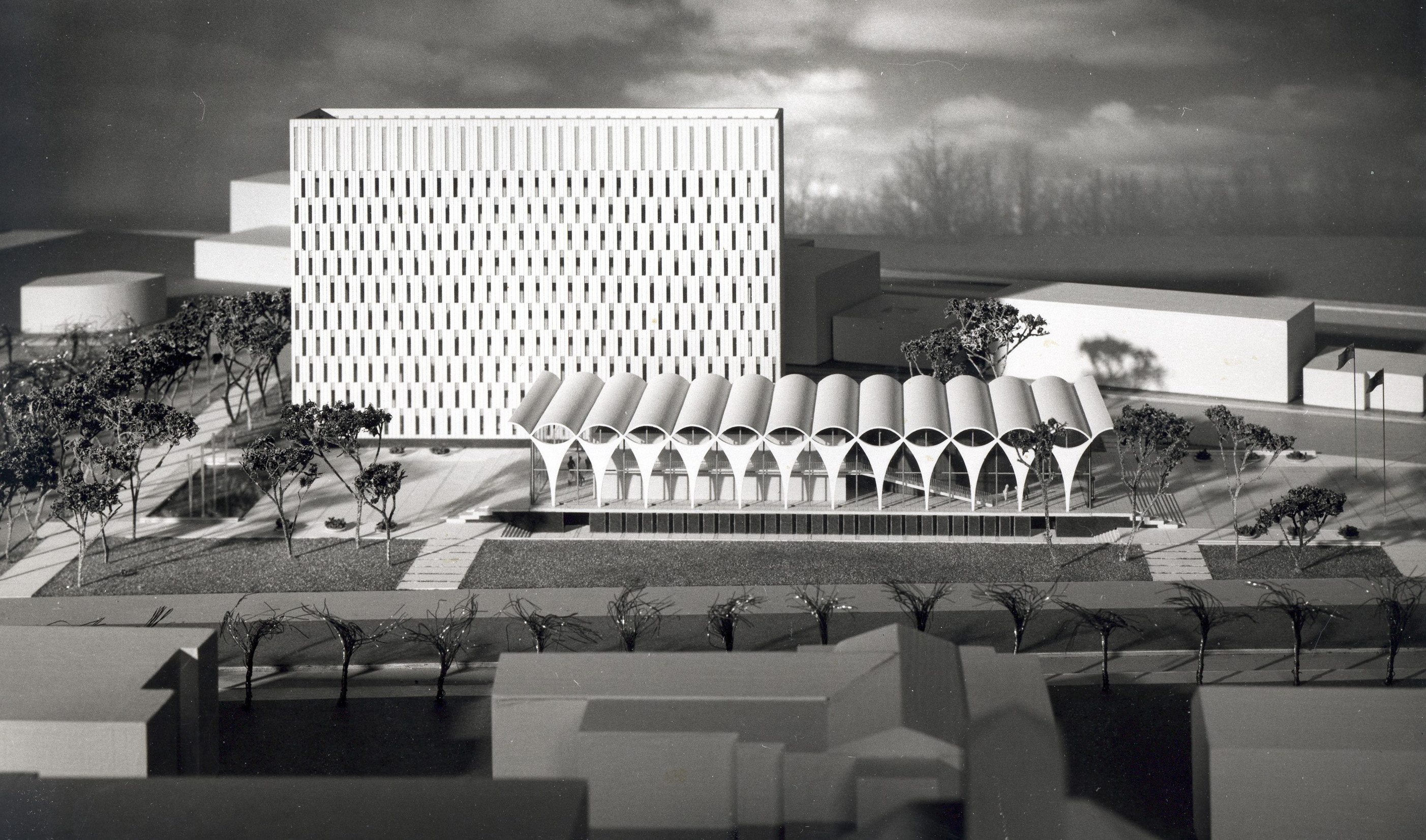

The winning entry in this competition was announced 16 December 1959. The unanimous choice of the five judges was the work by the Winnipeg firm of Green, Blankstein, Russell and Associates; the principal designers were Bernard Brown, Don Bittorf and David Thordarson. The winning scheme presented a distinctively modernist mode of expression; like most of the entries, it featured a two-building ensemble – a “sleek, thin” 10-storey glass and masonry tower and a “two-storey companion building where beneath a rolling roof of concrete corrugation, those city departments that deal directly with the public would be housed,” including the Council Chambers. (Winnipeg Free Press, 16 December 1959)

The reasons for this continued debate were largely related to the idea for a new arts and cultural complex on Main Street. This plan was put forward by the new premier, Dufferin Roblin. In June of 1958 the Progressive Conservative Roblin had replaced Premier Campell, who had granted Winnipeg the Broadway site for a new City Hall. That December, the new government’s plans for what was termed “a huge slum clearance program” in the South Point Douglas area of Winnipeg’s downtown were released. The proposal involved the spending of $13 million on a large civic centre to include the new City Hall, an art gallery and a library building. The city's share was to be $3 ¼ million, with the rest supplied by other levels of government. The offer was too good to refuse and on 23 February 1959 Winnipeg’s City Council voted 14-3 to support the urban renewal plans.

A major impetus for the larger civic and arts district project was the coming confluence of centenaries: the 1967 Canadian Centennial, the 1970 Manitoba Centennial and the 1974 Winnipeg Centennial. The first of these also meant that substantial levels of federal funding would be available for such endeavours. In 1960 the plans for the scheme were formalized by Premier Roblin and Maitland B. Steinkopf; three years later the Manitoba Centennial Centre Corporation was established, with Steinkopf chosen to oversee the project’s development. The complex which resulted from these efforts – the Manitoba Centennial Centre’s Centennial Concert Hall, Manitoba Museum and Planetarium, as well as the new City Hall, the Public Safety Building and the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre – introduced, on a large scale, architectural modernism in the heart of the city, not far from the historic Exchange District.

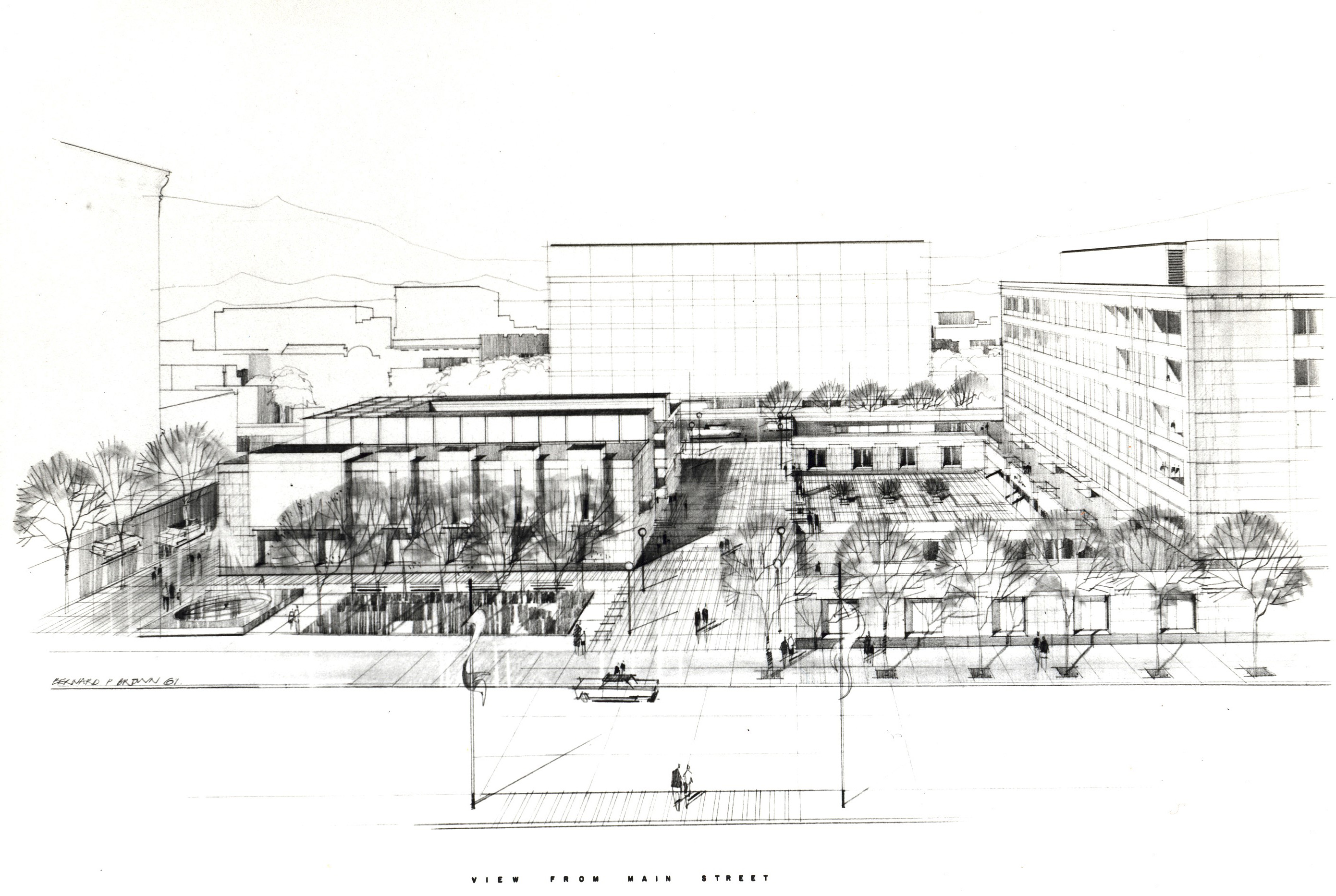

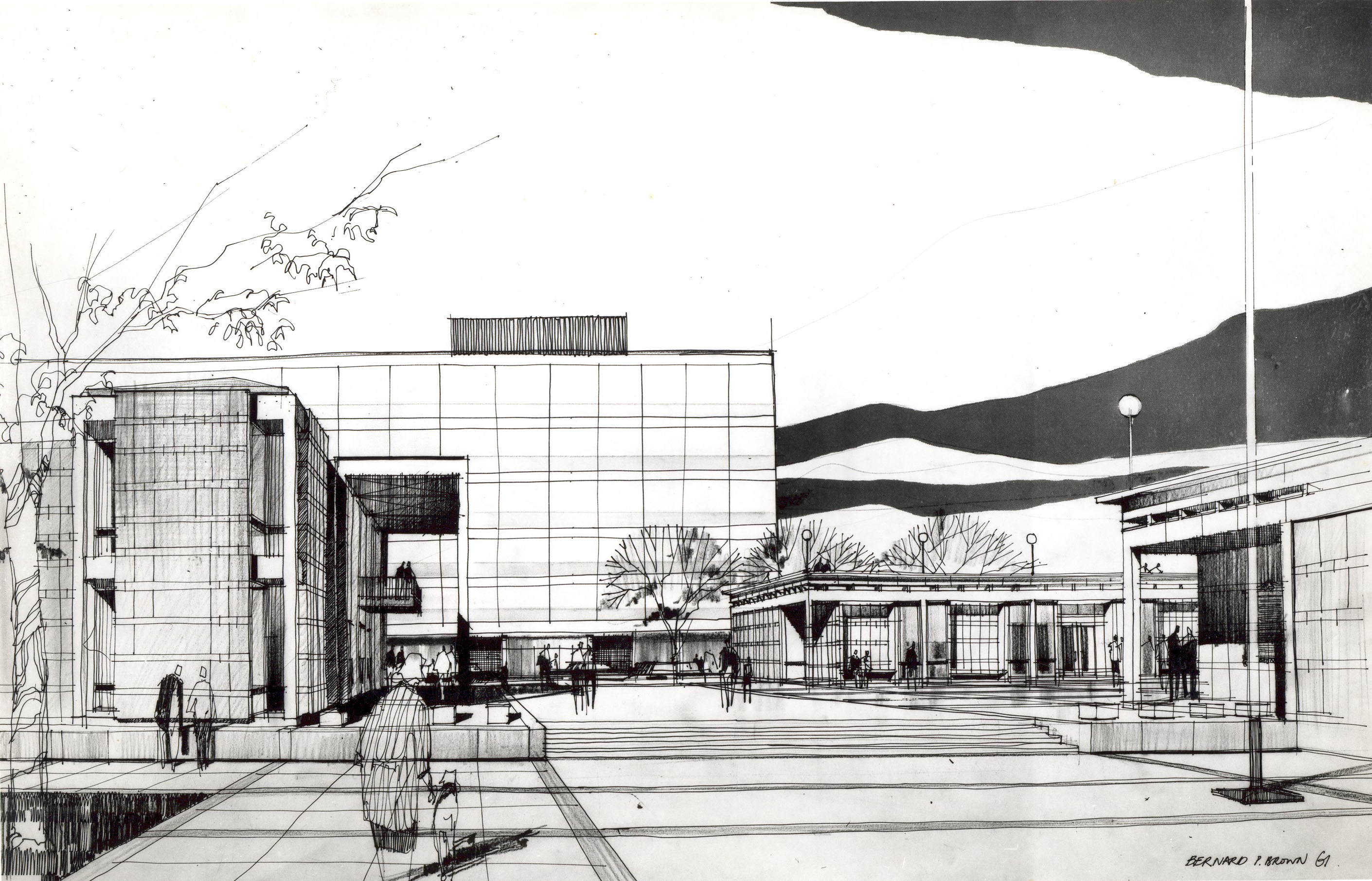

Construction of the new Winnipeg Civic Centre began October of 1962. Given the change in site from Broadway to Main Street, Green Blankstein Russell and Associates – and principal designers Bernard Brown and David Thordarson – substantially altered the plans from their competition-winning scheme. Winnipeg’s new City Hall maintained the earlier programme of a two-building pair composed of a slim, tall block for administrative functions and a shorter, more open block playing host to the Council Chambers. These two structures were set opposite one another with an open plaza between. This arrangement was motivated by the fact that the King Street site now holding the Public Safety Building was then intended to host the Greater Winnipeg Metropolitan government and Brown and Thordarson were thus required to maintain a clear view of this structure from the intersection of Market Avenue and Main Street and onward to the Red River. In addition, from the famous and prominent intersection of Portage Avenue and Main Street, the new building was situated such that it appeared to close Main Street, which here shifts toward the east.

From Main and King Streets, Winnipeg City Hall’s Council Chambers building presents a two and half-storey façade featuring a Tyndall stone colonnade. The guiding principal of the colonnade – and Civic Centre as a whole – is the alternation of short and long, with double-set columns standing between larger bays. On the east and west sides of the Council Chambers this design creates a three-bay set, with open spaces at the end of the colonnade lending a sense of expansiveness to the composition. Within the bays are set a defining detail of the building: three bronze screens suspended at a height of one storey. These screens – which now possess a dark green hue – recall the modernist trope of the brise soleil, a sun-shielding gesture popularized by Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, also known as Le Corbusier.

The Council Chamber building sits upon a podium of polished, charcoal-coloured, Quebec granite. Like the colonnade, this detail is somewhat reminiscent of Classical Greek and Roman models of temple architecture – as well as neo-Classical and Beaux-Arts design – and lends a feeling of dignity and reverence well-suited to the structure’s important role. Beneath the colonnades this podium is accented with built-in benches of matching granite, creating an area for public seating and repose which relaxes the otherwise stately design. Behind the colonnade and screens, the building’s exterior wall repeats the doubled columns by means of engaged Tyndall stone pilasters. On the lower floor, between these pilasters, are a base of granite and alternating sections of green-hued glass block and slender windows; on the top floor, shaded by the screens, stands full walls of glass. One notable detail is the thin transparent strips which lie between the ceiling of the colonnade and the building itself – a light-admitting motif which is repeated throughout the ensemble.

The William Street façade of the Council Chambers continues the pattern of doubled, engaged pilasters found on the building’s other sides, with sections of glass block and clerestory windows likewise repeated across its three bays. The same can be said of the interior-facing North façade, though here the exterior bays feature large second-storey windows. In addition, on this side the central bay is set back into the Council Chambers building itself, creating a grand, sheltered portico-style entrance. In this space walls of glass granting a sense of openness between the interior and exterior, citizen and government. This area also features a second-storey balcony atop a small glass and masonry vestibule, set close to the mayor’s office, suitable for public addresses.

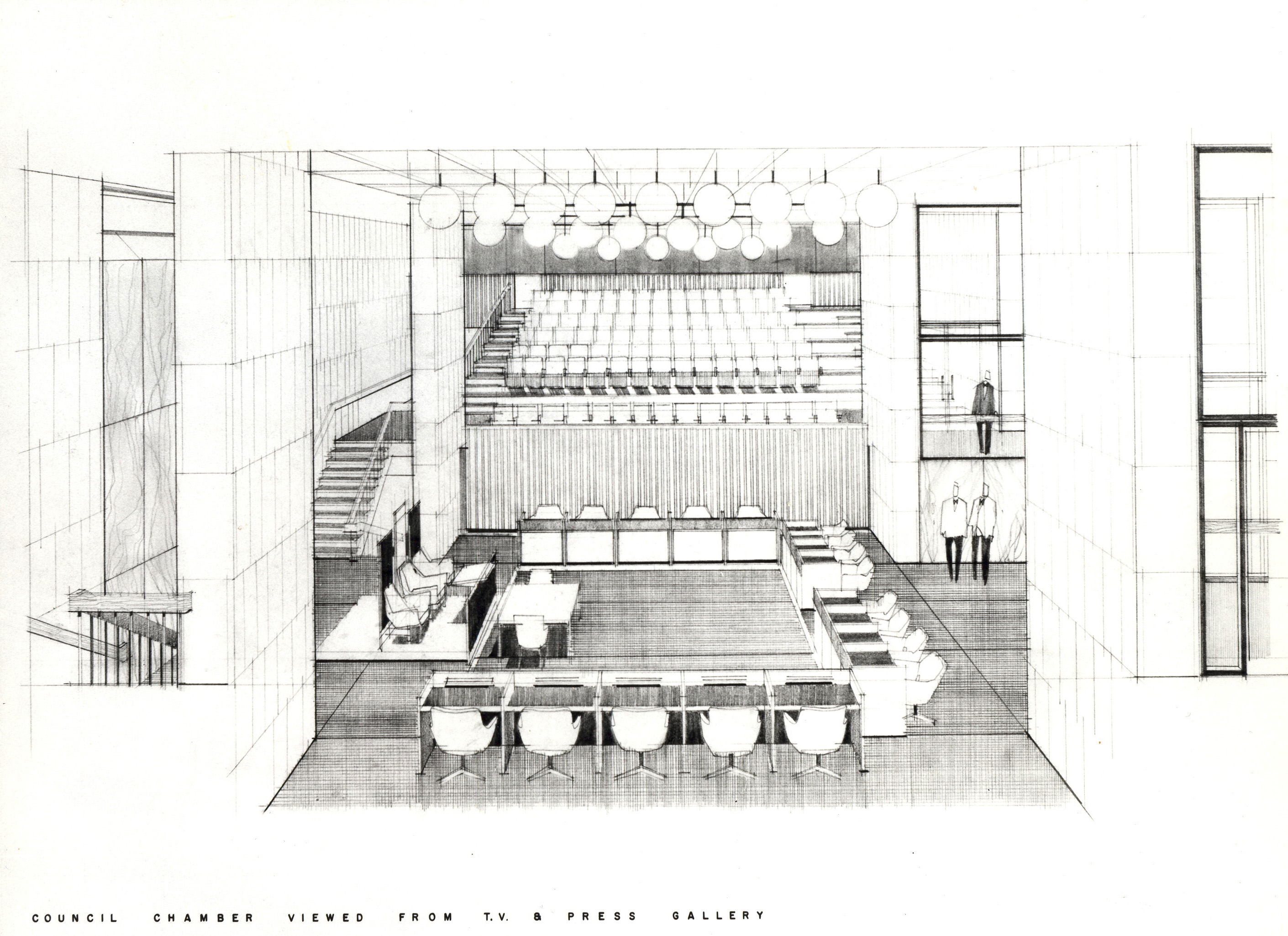

The interior of the building is treated with Tyndall stone throughout, the floors being of a rich charcoal terrazzo. The Council Chamber building was designed to house the civic law department and city clerk's offices on the first floor, with the council floor, a 200 seat gallery, the mayors office, committee rooms and aldermans lounge on the second storey. The basement was to contain voting tabulation rooms, a small museum and a press room. Due to budget constraints, the museum was never built. From the structure’s atrium it is possible to see the Council floor, which is level and open to the mezzanine landing; the purpose of this detail, as put by the designer Bernard Brown, was “to give citizens closer contact with the politicians." From this landing one can also see the entrance and second floor lobby of mayor’s office; this fact – in combination with the extensive use of interior glass, clerestory windows and the glass entry wall – grants the building a remarkable sense of openness and clarity. The council floor itself receives considerable natural lighting from two double-height, south-facing glass block windows, two skylights and clerestory windows; it is furnished with custom lecterns and partitions of chestnut toned wood, with bronze detailing in the treatment of a number of architectural and decorative details. As with the use of masonry, the use of bronze was selected by the architects to suggest a feeling of dignity and importance.

Like the Council Chamber building, the City Hall Administrative building rests upon a podium of polished, charcoal-coloured Quebec granite. Here however, the structure itself meets the sidewalk and is without the open, platform surrounding the legislative block, appropriate given the less august role of this side of the complex. The south-facing entry façade looks across to the main entry of the Council Chamber and fronts onto an intimately scaled courtyard. Originally this space centred upon a wide, square pool with a fountain at its heart, its enclosure made of matching charcoal granite. This was accented by two matching square planters in the north-west and north-east corners containing, respectively, an angular cherry tree and seasonal blossoms. The spaces’ designer conceived as the space as a possible host for a weekly market – given that the nearby historic city market was to be replaced by the Metropolitan administration’s offices – but then Winnipeg Mayor Stephen Juba is reported have stated:”There'll be no chicken farmers around my City Hall.”

In 2003 this courtyard was redesigned by the firm of Scatliff Miller Murray; the new arrangement features a smaller, off-centre fountain set at-grade in the north-east corner, surrounded by sculptural masses of rough limestone. At this time a large number of Japanese elms were also planted in the plaza – though the original cherry tree remains – and decorative, graphic paving in tones of cream, charcoal and burgundy were installed. The courtyard is semi-enclosed by two one-storey wings which run parallel to and block Main and King Streets. Together with the main section of the Administrative block, these wings are fronted by a peristyle colonnade which lines up with that of the Council Chamber. The cloister-like character of this feature enhances the intimate feeling of the space. Near the tower and entryway portion of the peristyle are set two large openings; these were originally conceived to hold staircases to connect with a landscaped, public garden on the second level. This colonnade is topped by a short balustrade of limestone, which sports doubled supports – a detail which recalls the double-columned motif of the complex as a whole. This balustrade surrounds what was originally intended to be a second-story roof-top patio, though this aspect was left out due to budget cuts. Following the 1972 unification of Winnipeg with twelve adjacent municipalities, ceramic depictions of the crests of these communities were installed also this courtyard.

Underneath the plaza, the two parts of the Civic Complex are connected via a tunnel. This long underground gallery was initially intended for mayors’ portraits. At ground level, the two shorter wings along the east and west sides of the courtyard were designed to play host to the taxing and welfare arms of the civic government; Bernard Brown, the designer, has poetically described these sections as one hand taking and the other giving back. At the moment the west wing houses a café, while the east wing sits vacant. These sections – and top five storeys of the north and south façades of the Administrative tower – feature walls which recall the design of the lower storey of the Council Chambers. Here double-set Tyndall stone pilasters form a grid with matching spandrels; suspended within the bays this grid creates are walls of green-tinted glass block and windows. In the tower, these bays also feature balustrade-like sections of charcoal stone. The second-storey of the tower, which looks upon the intended roof-top garden, has these bays filled with large blocks of polished granite alternating with banks of windows. This detail lends a feeling of depth and immateriality; the result is that the top section of the building seems to float above an open space. In this way the tower recalls the typically modernist gesture of a large block held atop a void, the pilasters thus paralleling what are otherwise known as pilotis. On the east and west sides, the tower has at its centre windows with matching balustrades of charcoal stone; the façades are otherwise made up of large expanses of Tyndall stone. The lower portion of the James Street side of the administrative block also holds an entryway to a loading and parking areas.

Design Characteristics

- Approximate cost of construction: $5.5 million

- Council Chambers building sits upon a podium of polished, charcoal-coloured, Quebec granite

- Granite benches at base of podium

- Building interior treated with Tyndall stone

- Floors of charcoal terrazzo

- Original design included a museum in basement level (never realized)

- Extensive use of interior glass, clerestory windows and open interior volumes

- Tunnel underneath plaza

Sources

- "Competition for City Hall design won by local group." Western Construction and Building 12 1 (January 1960): 20-21.

- "Interior Designers Gain Ground." Western Construction and Building 19 4 (April 1996): 33-34.

- Lahoda, Gary. "Civic Centre: destined to be Canada's ugliest?" Winnipeg Tribune. 18 April 1964.

- Lehrman, Jonas. "Downtown Winnipeg: A Need for New Goals." The Canadian Architect 20 6 (June 1975): 45-54.

- Matoff, Theodore. "City Hall: Prudence in Tyndall stone porridge." Winnipeg Tribune. 5 December 1964. 1.

- "Transportation and Services." Greater Winnipeg Industrial Topics (Metropolitan Winnipeg edition) 22 11 (1962): 12. "Transportation and Services." Greater Winnipeg Industrial Topics (Metropolitan Winnipeg edition) 23 11 (1963).

- Werier, Val. "Behind the News: City Hall isn't that bad." Winnipeg Tribune. 3 October 1964. 6.

- "Will City Hall Set Style?" Financial Post. 7 April 1962. 69. "Winnipeg Builds a City Hall." Winnipeg Construction and Building 16 9 (September 1964): 13-26, 29-30.

- "Winnipeg City Hall." Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada 40 1 (January 1963): 30.

- "Winnipeg City Hall." The Canadian Architect 10 1 (January 1965): 51-55.

- "Winnipeg's $7 Million City Hall." Greater Winnipeg Industrial Topics 22 1 (January 1962).