Buildings

67 Duluth Bay

| Address: | 67 Duluth Bay |

|---|---|

| Architects: | Unknown |

| Contractors: | Quality Construction (Qualico) |

More Information

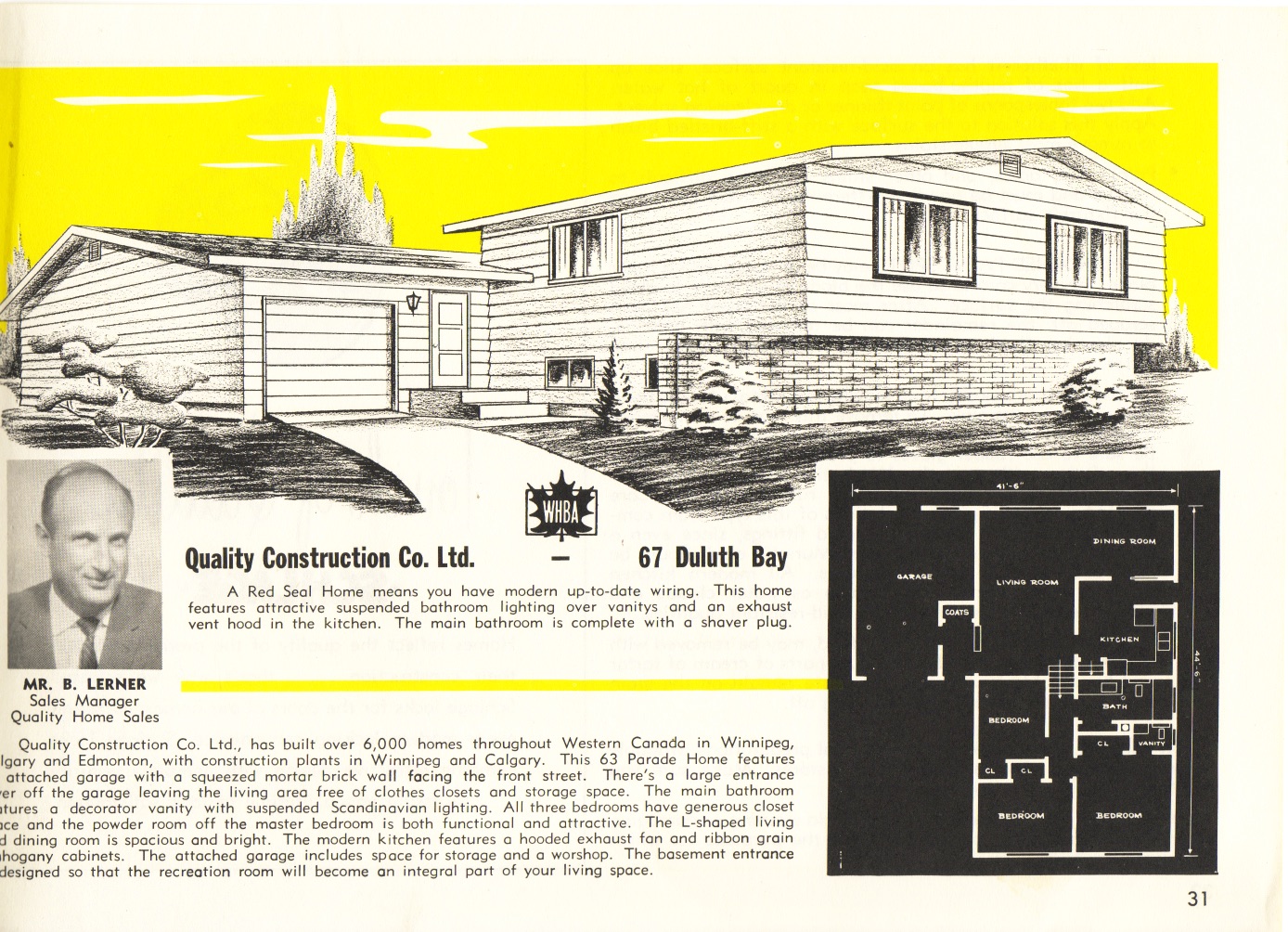

67 Duluth Bay features a “squeezed” mortar brick facade for the lower level of the split-level, juxtaposed against the wood finish of the upper level. The entrance to the home is recessed between the house and the attached garage, with separate closet space at the back so as to not clutter the living room with storage space. The living room and dining room is in an “L” configuration along the back and through the centre of the house. The basement was designed to be used as a recreation space.

Windsor Park was the first master-planned community in Winnipeg, the largest housing development of its kind in Western Canada, and the second largest in the country.

A master plan created by Green Blankstein Russell and Associates (GBR) of Winnipeg called for 3,041 homes of all types, including duplexes and apartments, creating accommodation for 13,000 to 15,000 people. Irvine B. Margolese and Co. Ltd., was responsible for the development of nearly 1,500 of these homes.

Windsor Park was a departure from the common rectangular grid suburb, with only a few points of entry, and only two main roads that bisected the development. Unlike other suburbs, which were often strung along major traffic arteries, Windsor Park’s limited entry points kept it relatively secluded from the rest of the surrounding city. Streets were organized in loop or bay patterns, separating circulation streets from local access streets in order to reduce traffic and noise; improve safety; and make Windsor Park more aesthetically pleasing. Conducive to easy navigation, streets were organized alphabetically.

Pedestrian accessibility was also considered, with a particular emphasis on child safety. Children walking to school from almost half the homes in Windsor Park would not need to cross a single street, using paths at the end of each bay to access park walks that connected to their school. Preschool children could also make use of playgrounds and “tot lots” accessed by the paths at the end of each bay.

Befitting the name of the development, parks and green spaces occupied fifty acres. As part of the central plan, shrubs, and even fruit trees, were planted on residential properties. Where possible, naturally growing shrubs and trees were preserved.

The rapid development of Windsor Park could be attributed to new techniques in home building that significantly reduced the time required to build a home. For companies such as Quality Construction Co. Ltd. (later Qualico), much of the construction took place off-site at factories using assembly-line type manufacturing, and then transported to the construction site. Pre-fabricated components included rafters, window and door frames, and kitchen arrangements including cabinets, while walls could be assembled within 14 hours of being cut. The 1957 Winnipeg Housebuilder’s Association Parade of Homes, a showcase of newly constructed homes, featured Windsor Park, and opened with a show of building efficiency. Between 5:00 pm September 21 and 5:00 pm September 22, a home was built by Quality Construction, omitting time to prepare the foundation. A record had been set in Toronto a few weeks earlier, with a home built in 21.5 hours. Quality Construction claimed the event was merely a demonstration and not an attempt at beating the record. Two hundred company employees and subcontractors worked on the project. The house, located at 3 Cherry Crescent, was built in 19 hours and 10 minutes, with an additional 20 minutes to furnish it.

With modern construction techniques, including the Winnipeg-developed practice of winter construction, it was estimated that 1,800 homes could be built in 1956 alone. However, rapid home construction often meant that homes were finished and occupied before accompanying infrastructure could be completed. By the summer of 1957, residents complained of unpaved streets and sidewalks, as well as the lack of street lights. Despite an investment of $2.1 million in infrastructure and services by Ladco, revenues generated from lot sales were able to cover only $1.3 million. The issue continued, and on July 14, 1958, St. Boniface city council was pressured to establish a five-man committee to investigate the delays.

Despite associated difficulties, home development in Windsor Park continued at a fast and unabated pace. It was estimated that by the planned completion date of 1958, Windsor Park would be home to 14,000 people, resulting in a 50 percent increase in the population of the City of St. Boniface. This climate of speculative growth contributed to St. Boniface leading metropolitan Winnipeg in housing development. In 1956, home sales in St. Boniface totalled $4,590,300, while $6 million worth of housing permits were issued. St. Boniface, and by extension, Windsor Park, also helped metropolitan Winnipeg set a new record for housing permits value, supplanting 1955 by $2,186,145. Despite the number of permits issued in metropolitan Winnipeg in 1956 falling to 122 fewer than in 1955, fast-rising home values continued to improve the profitability of the housing market. In St. Boniface, both the number of houses and home values went up, with 399 more homes built, and home values rising by almost 300 percent over 1955. By 1962, Windsor Park had 2,000 occupied homes and a population larger than Carman, Minnedosa, and Dauphin combined.

As a larger community, Windsor Park required its own services, civic spaces, and retail spaces. French and English language schools, a firehall, churches of various denominations, and both small and large retail spaces were erected, often designed in the modernist style, and embodying a progressive and playful attitude towards architecture. The result is an architectural legacy that is both modernist and unique to Windsor Park.

Design Characteristics

| Developer: | Ladco |

|---|---|

| Suburb: | Windsor Park |