Where Are the Women Architects?

This is a question that feminist historians have been grappling with since the 1970s. The result is an impressive collection of scholarship exploring women’s participation in the formation of the built environment. And yet, the continued exclusion of women in dominant architectural histories and the current climate of the profession, both in Canada and elsewhere, force us to continue to reflect on that question.

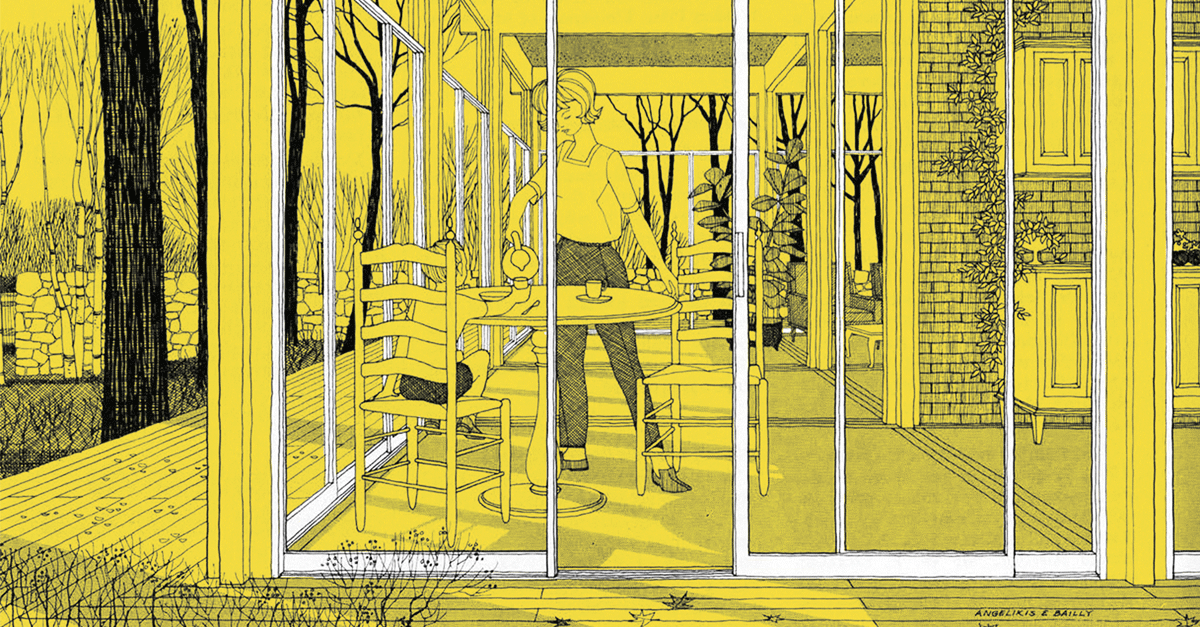

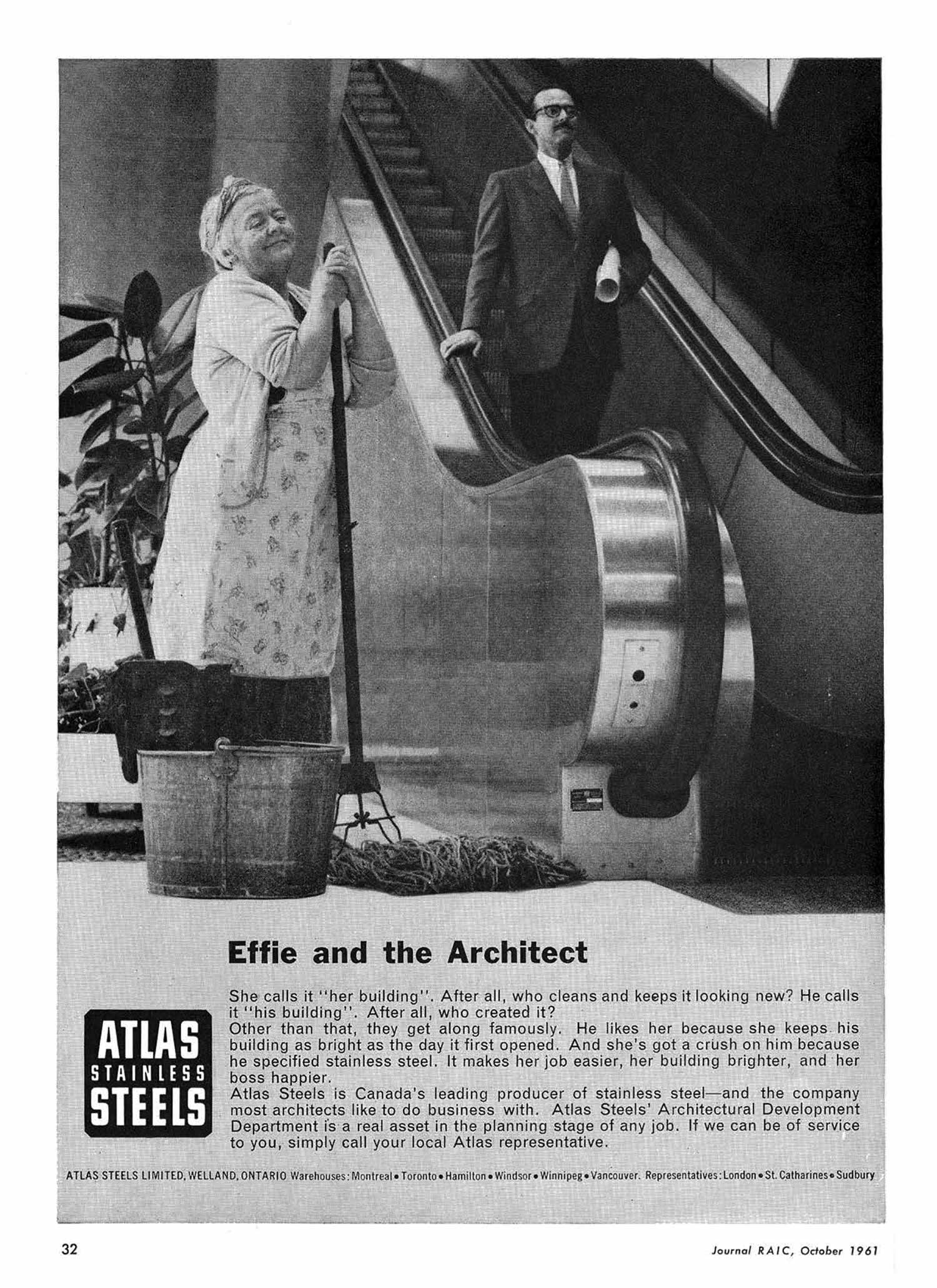

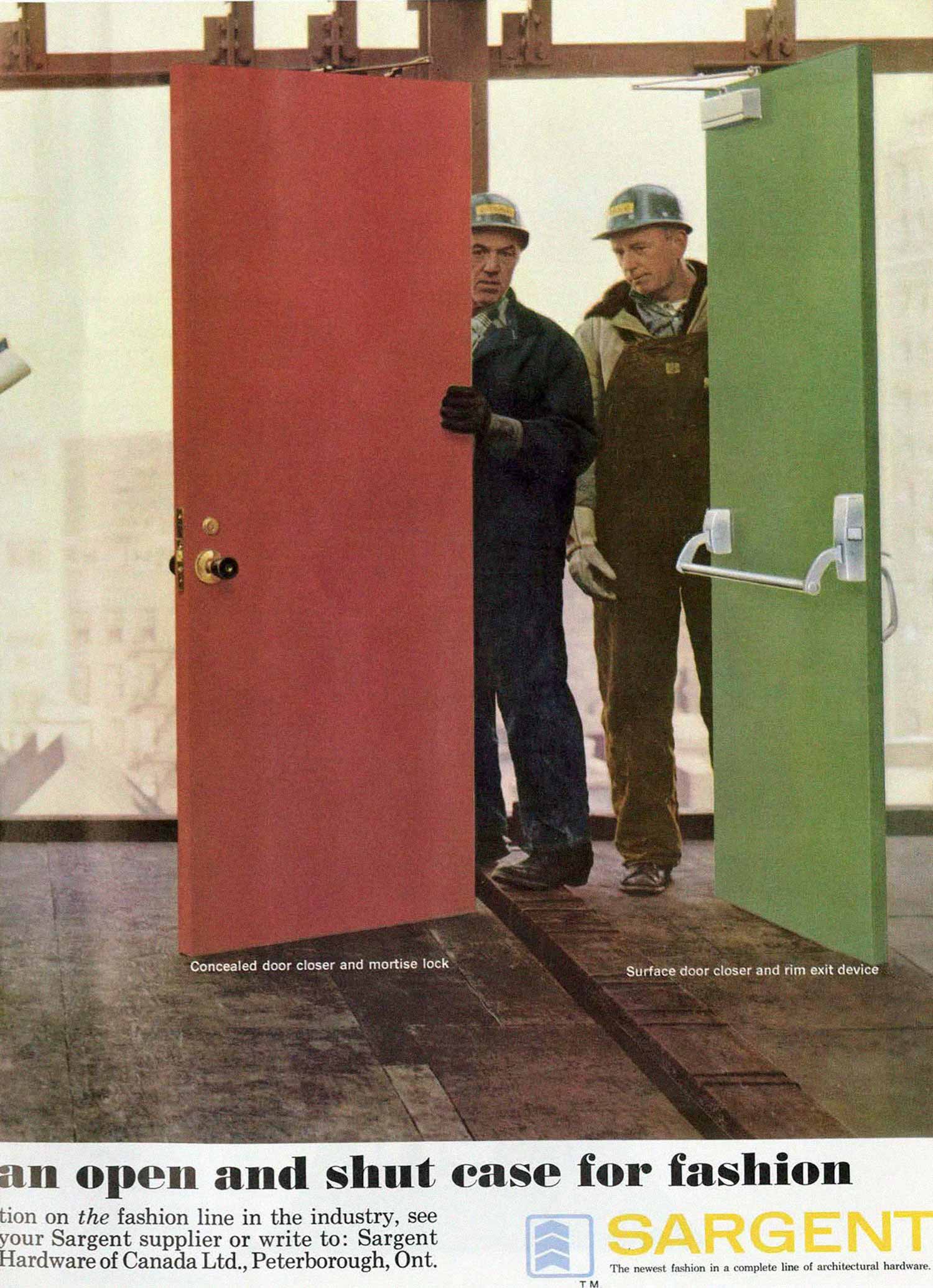

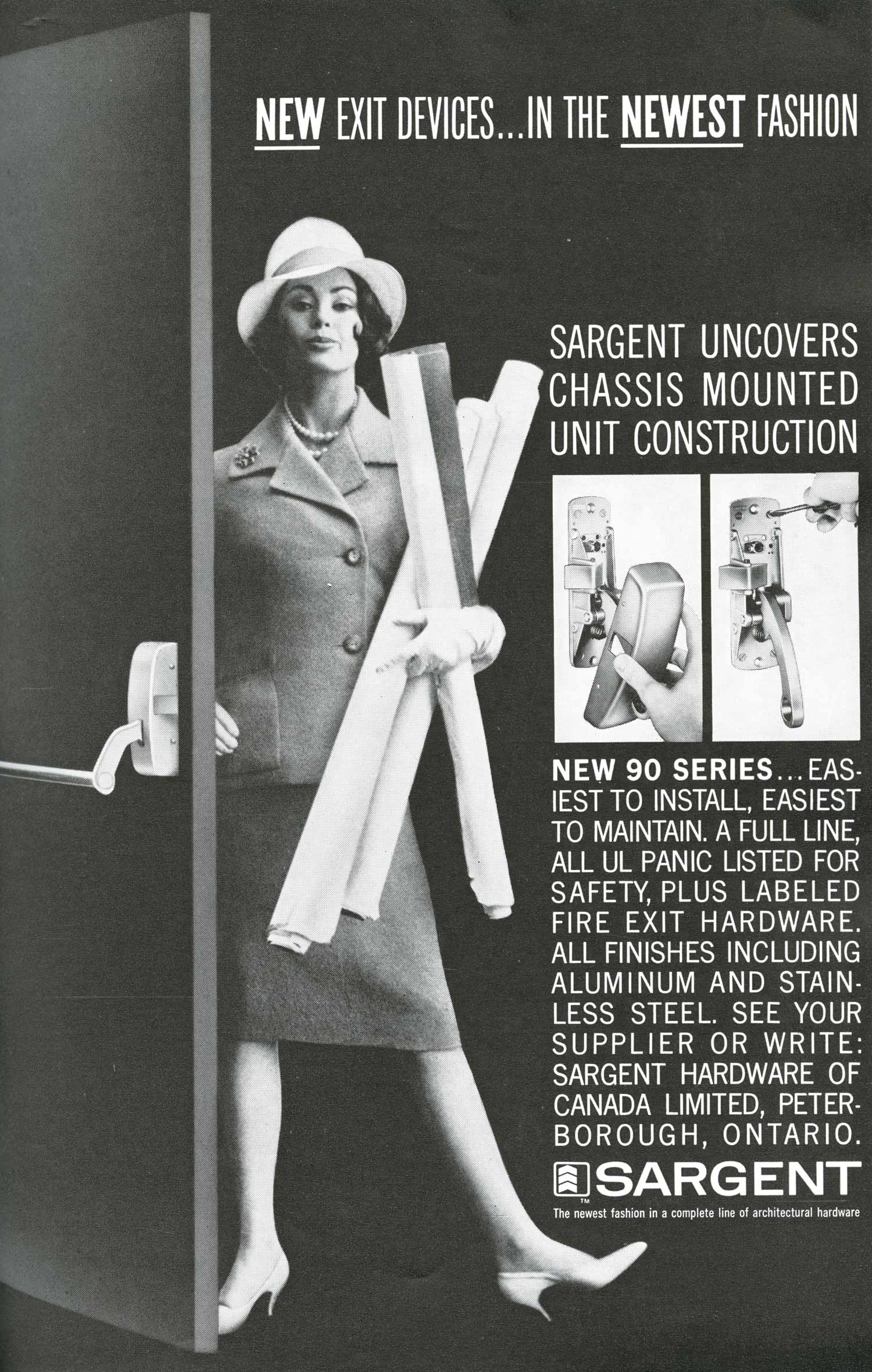

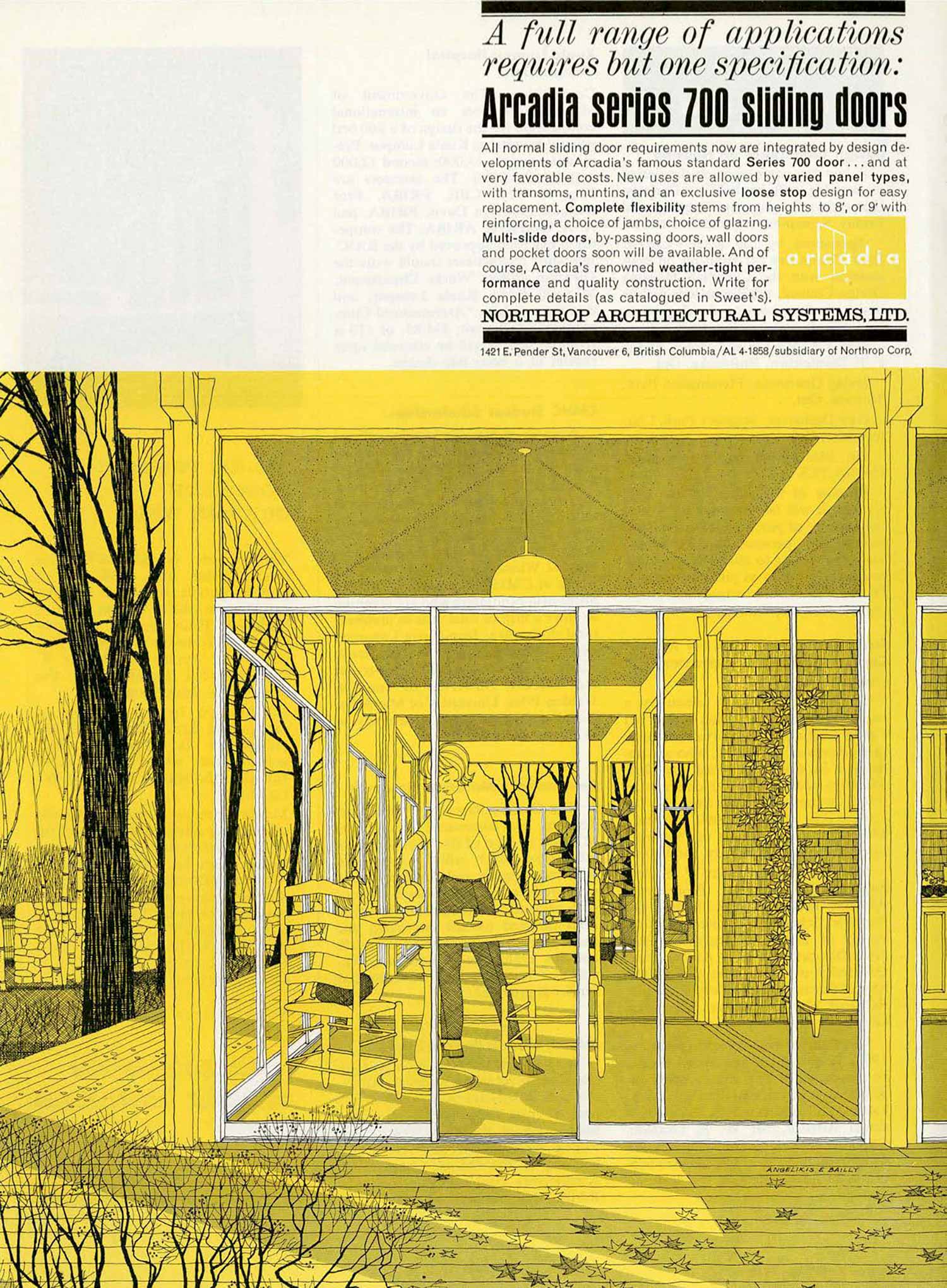

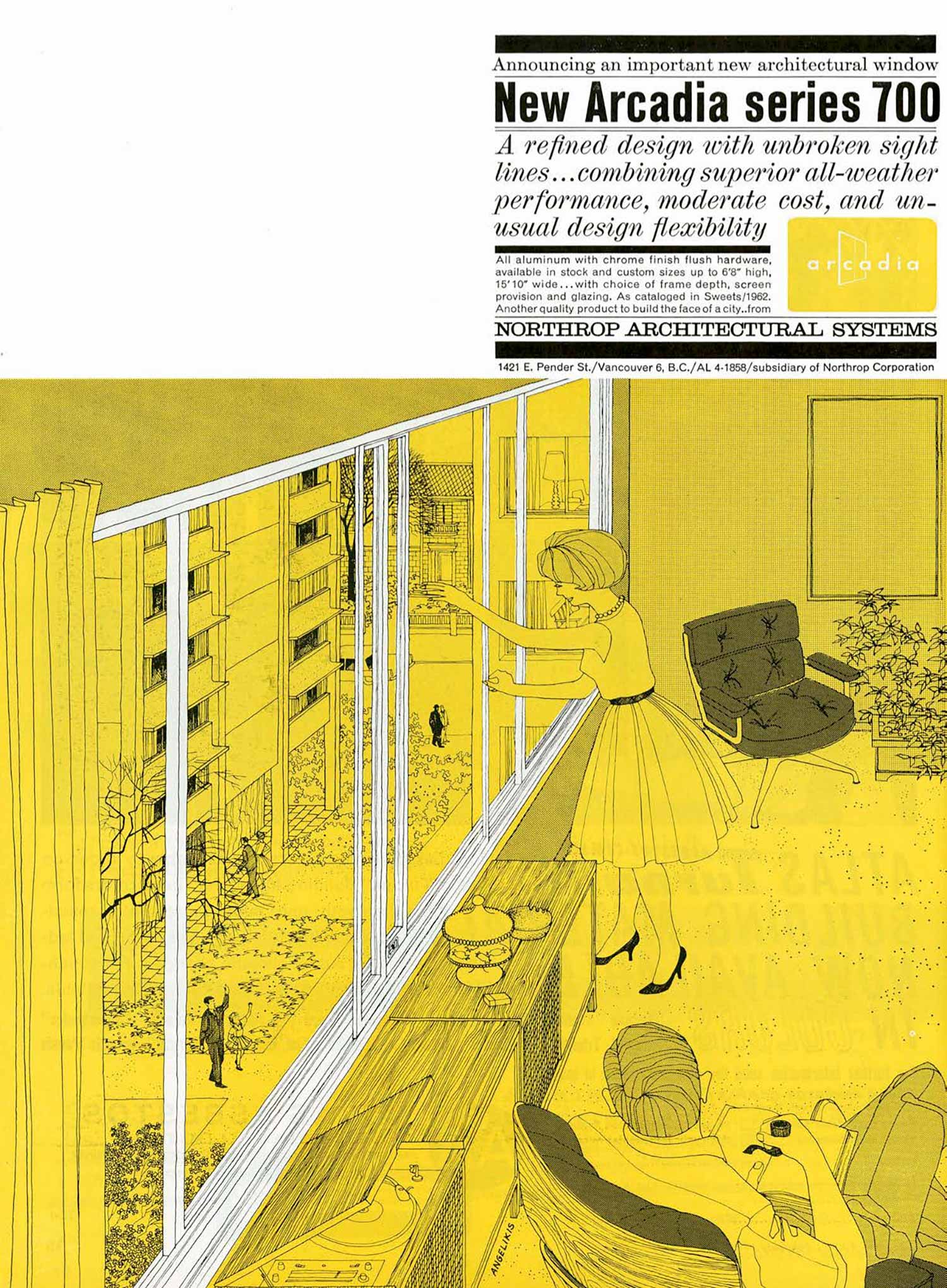

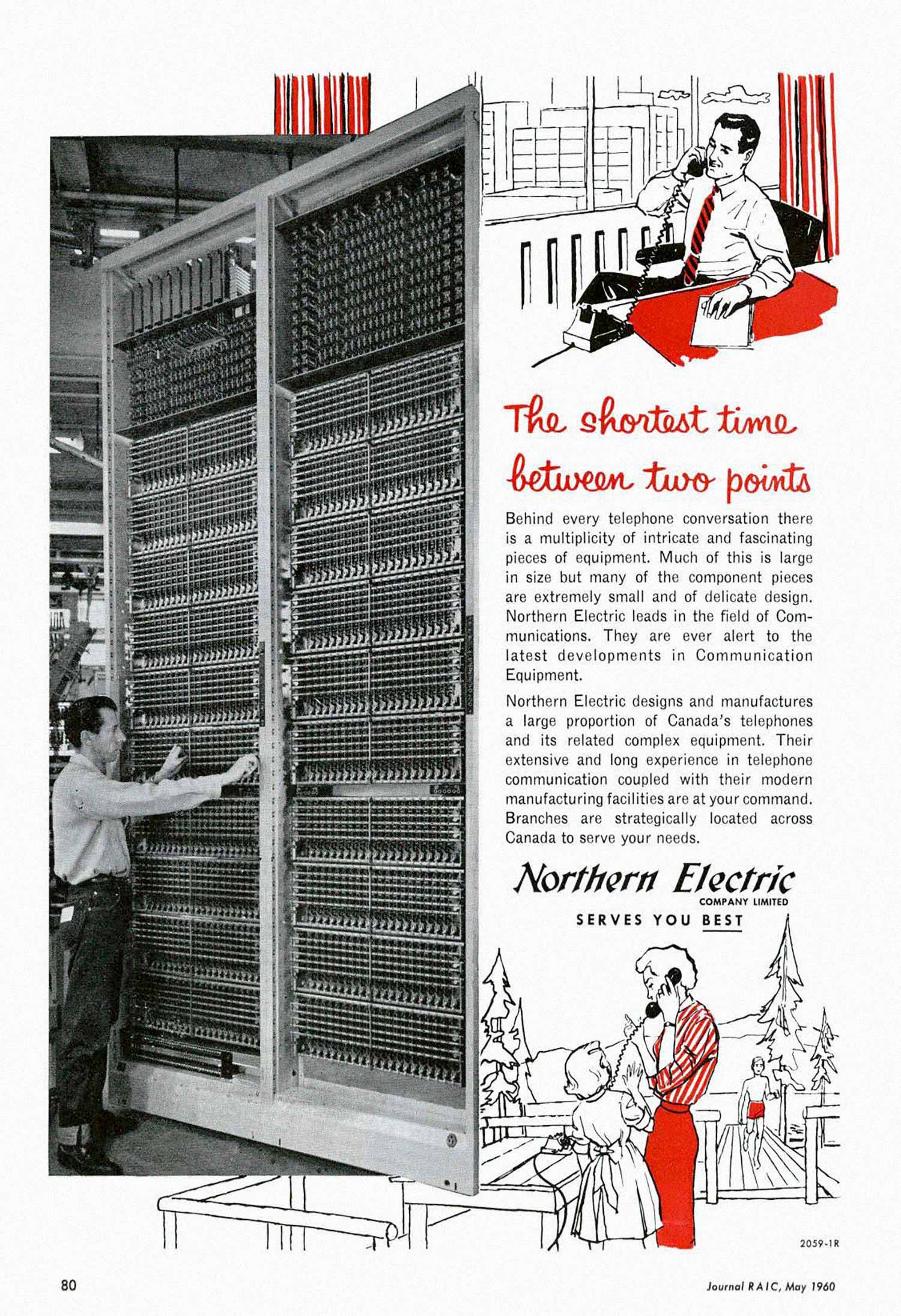

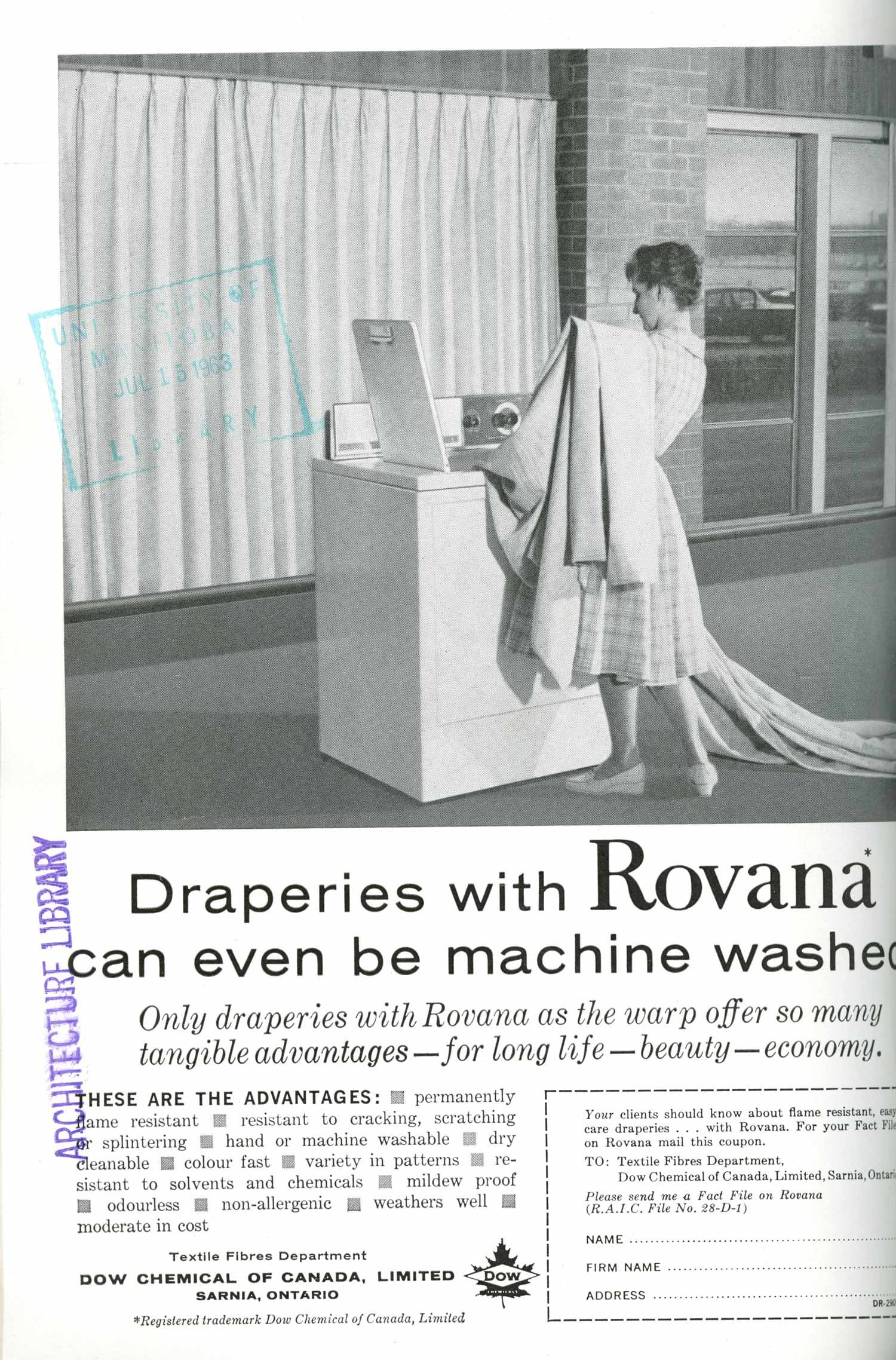

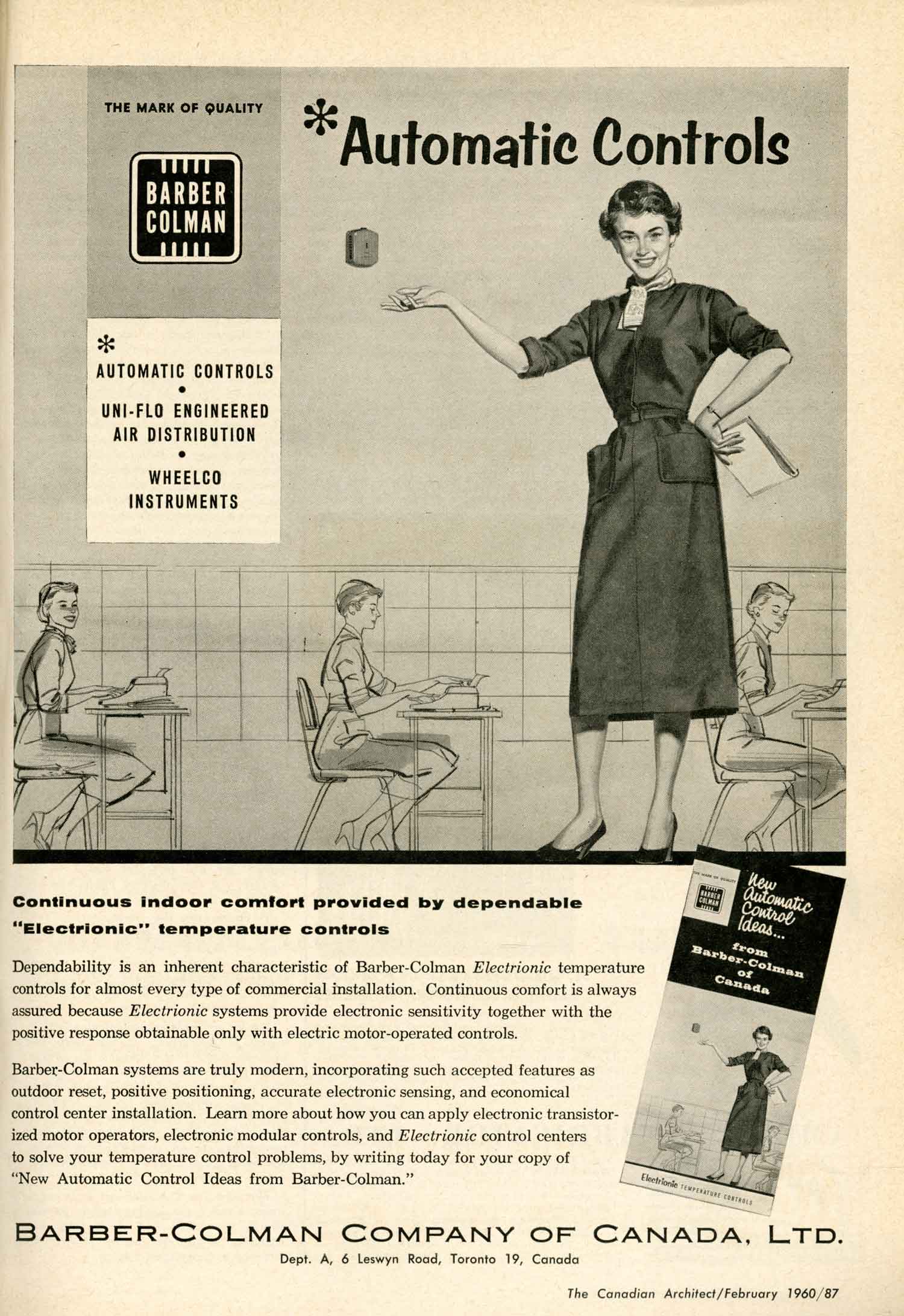

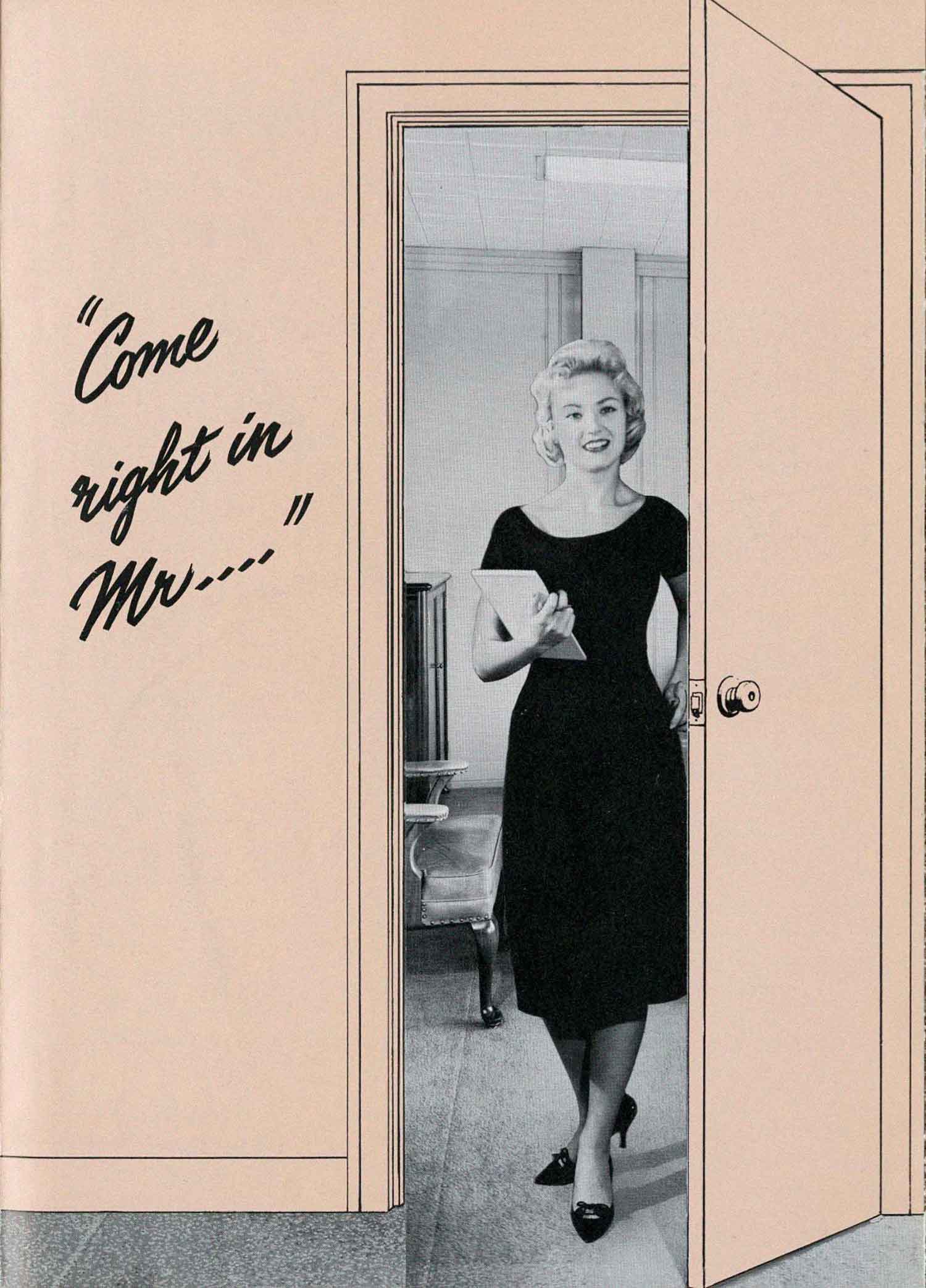

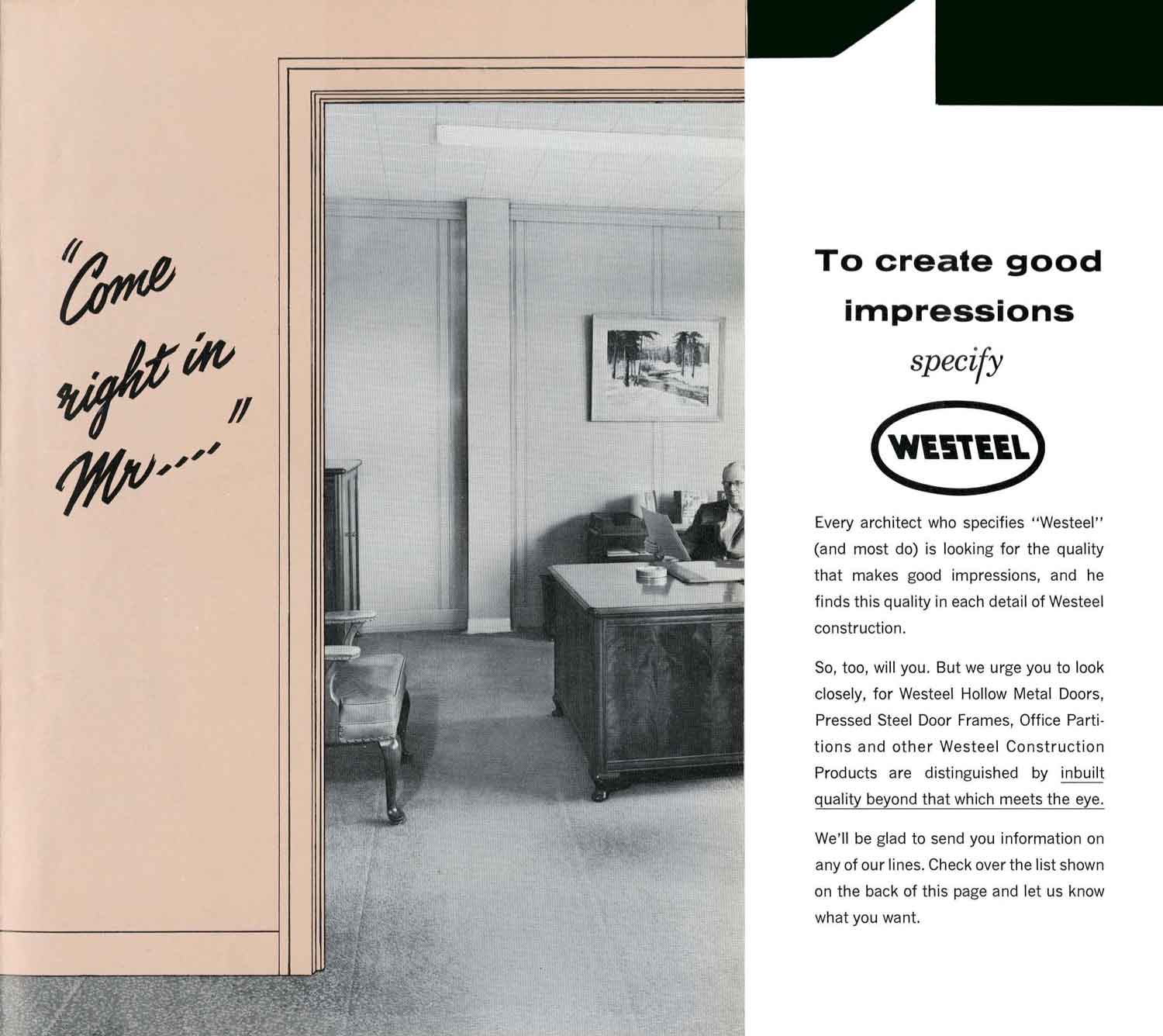

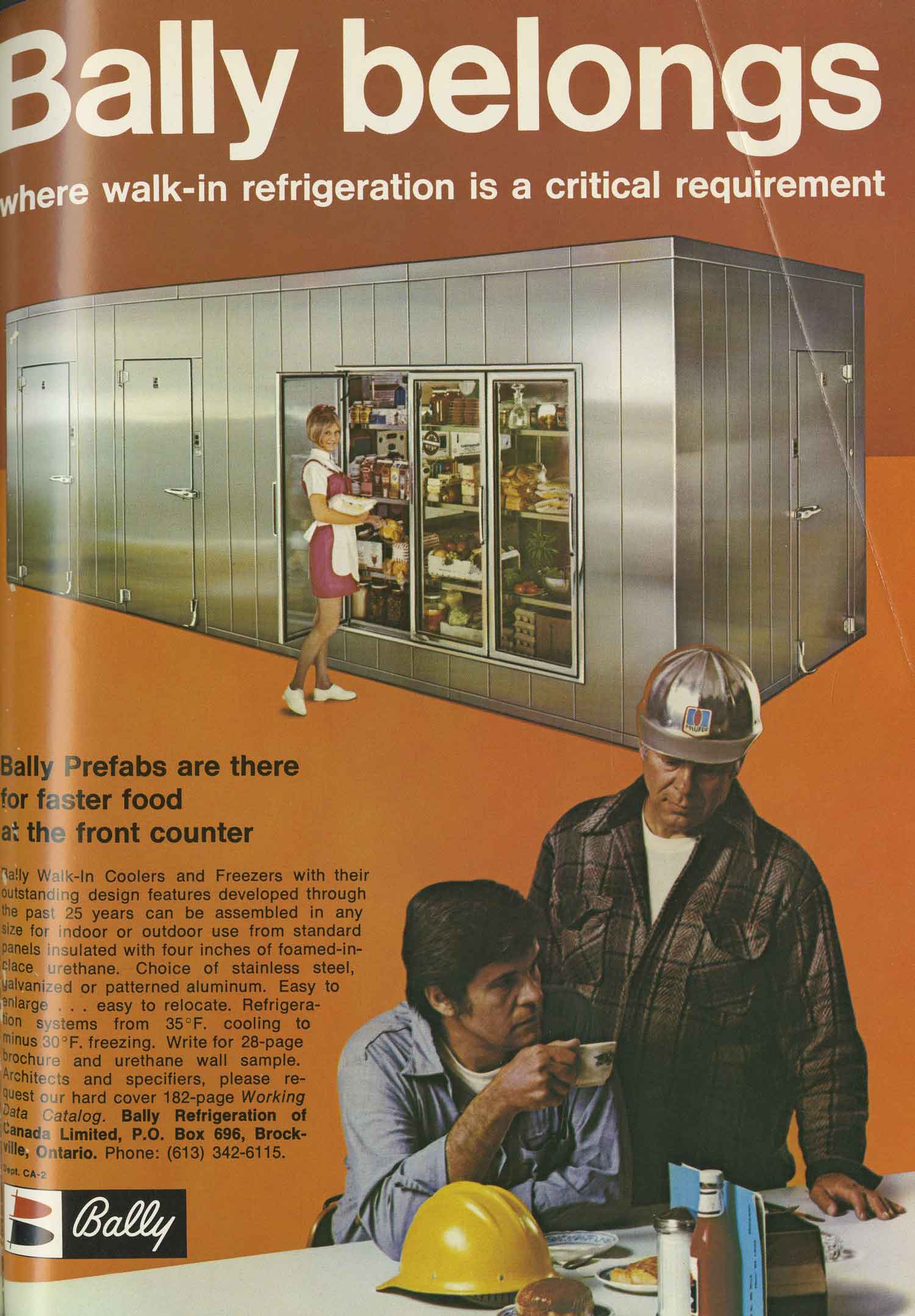

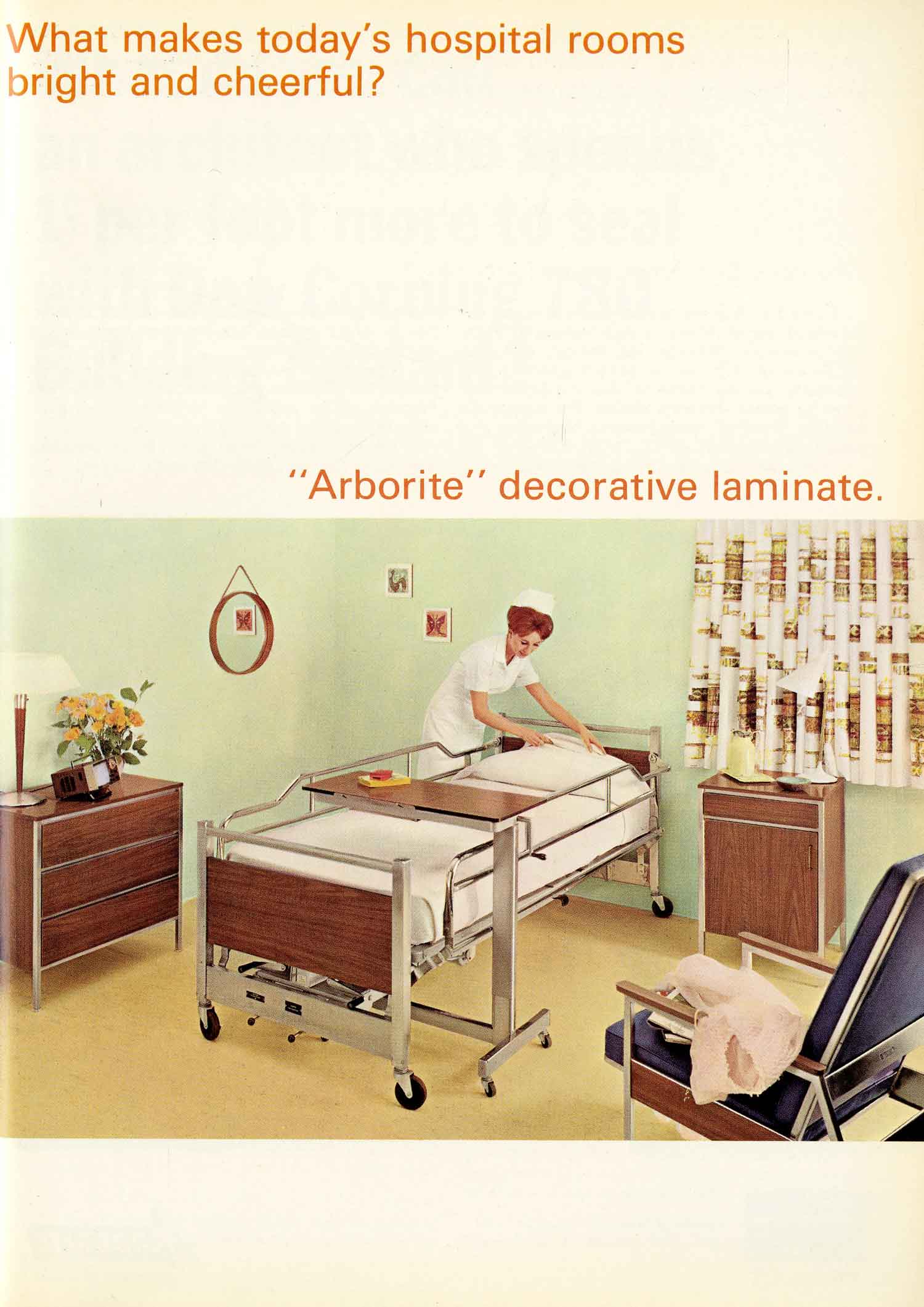

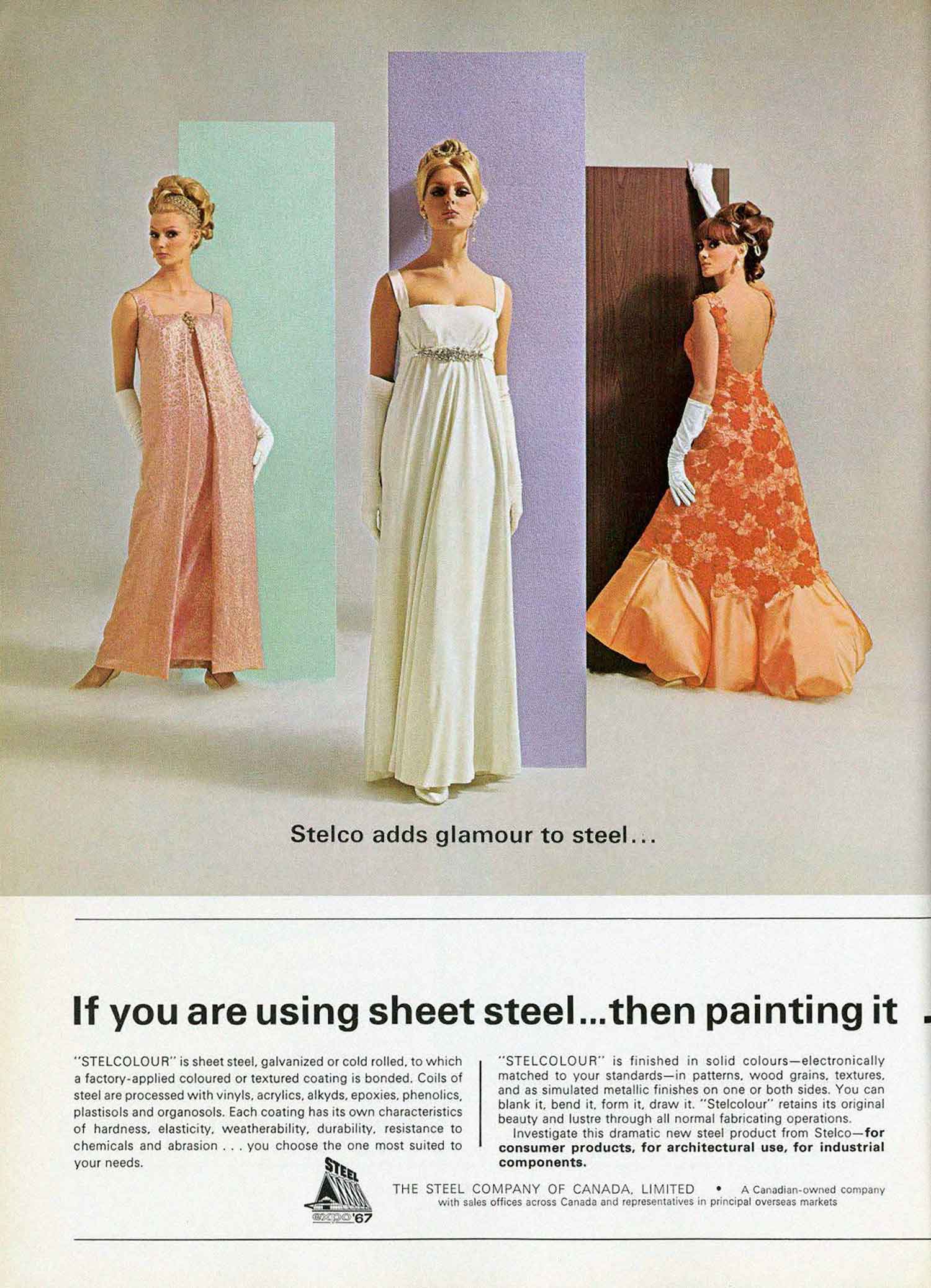

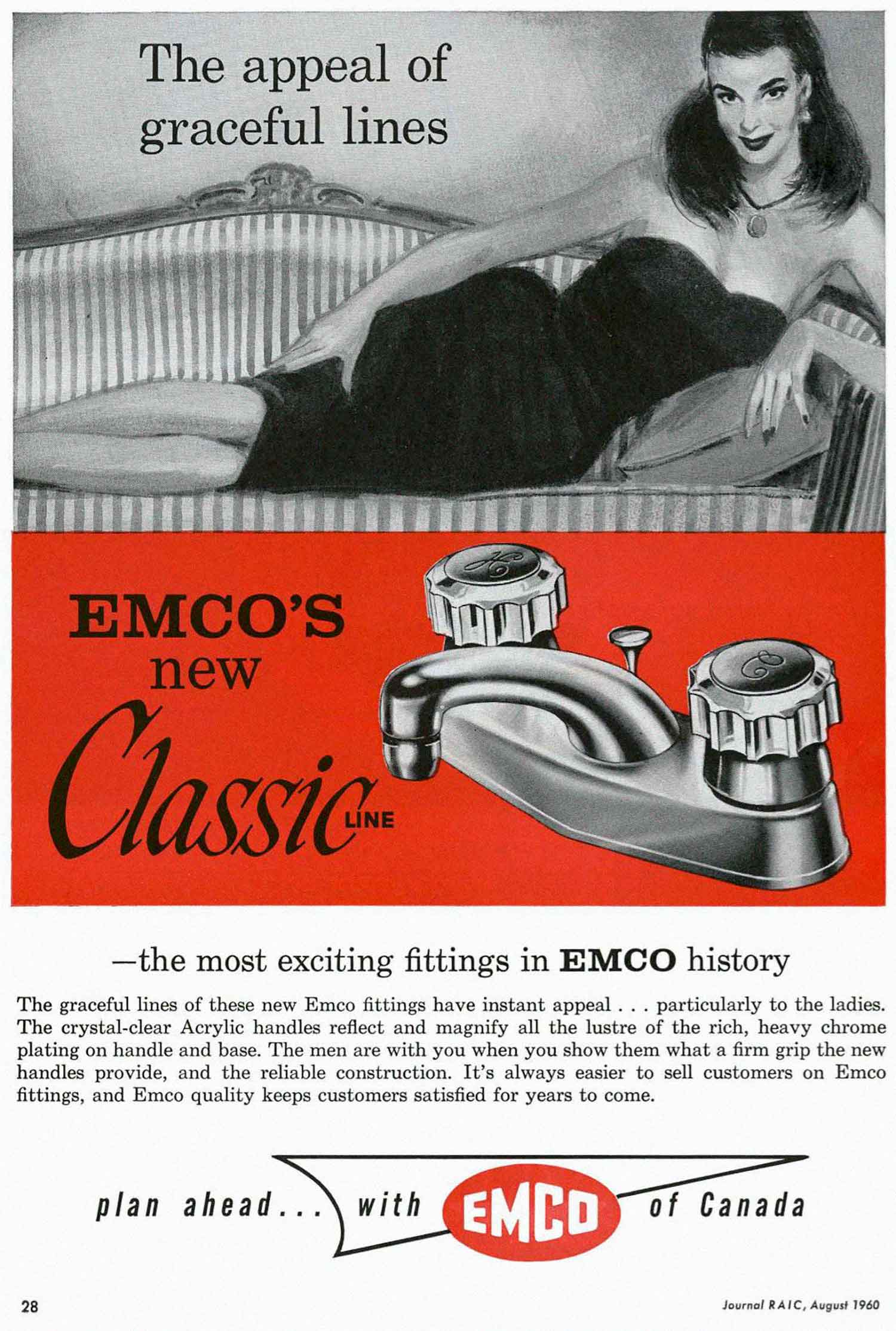

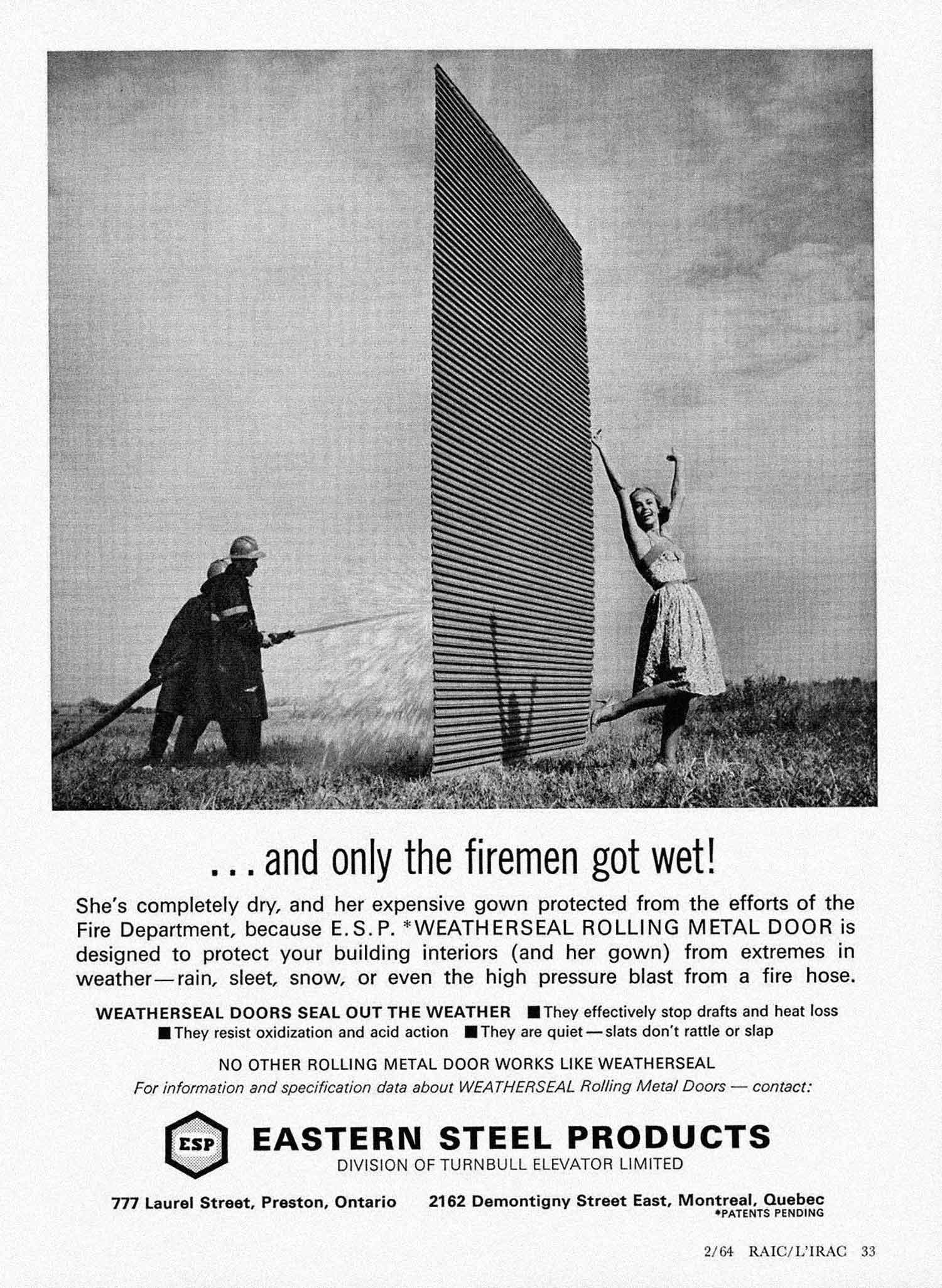

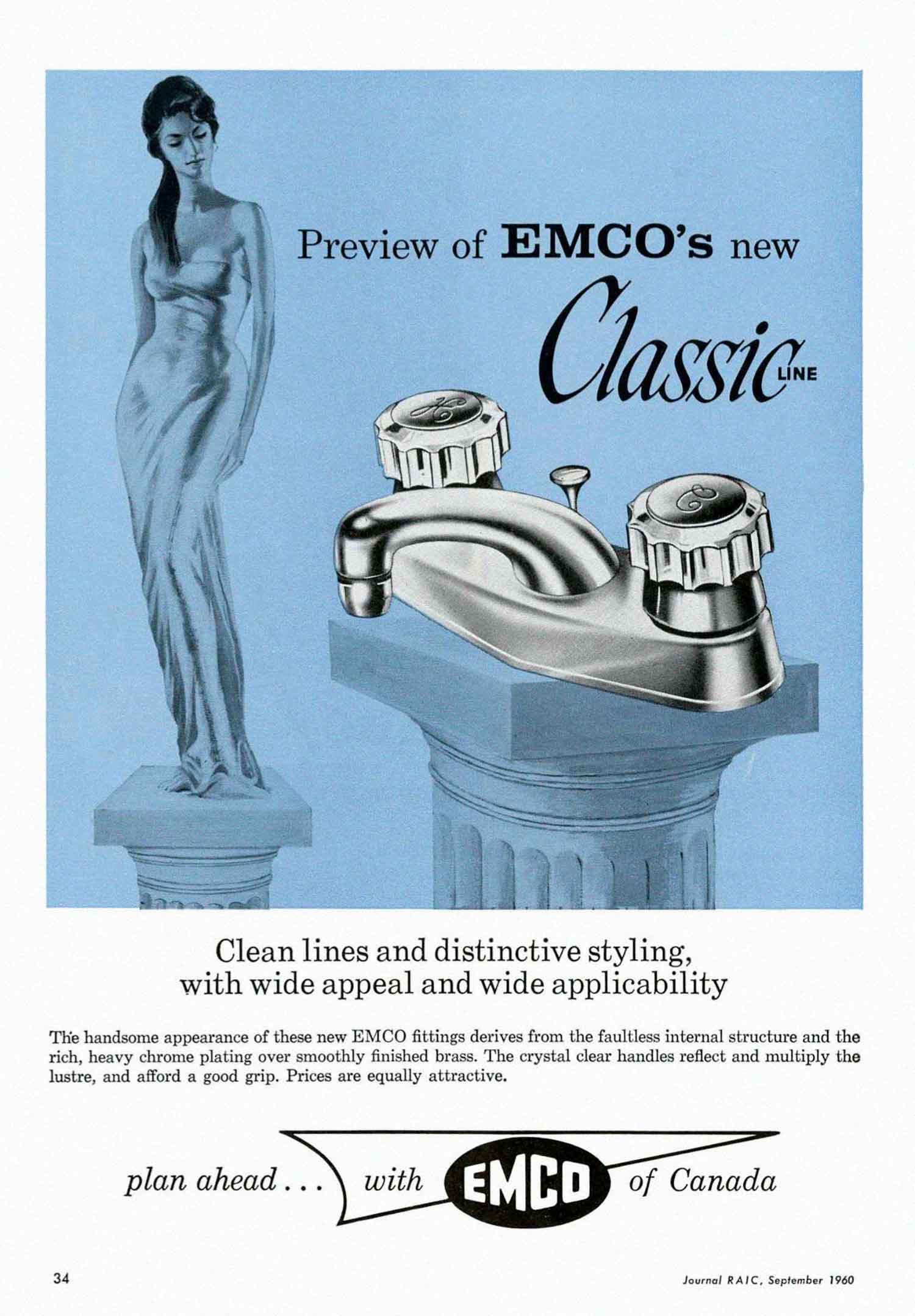

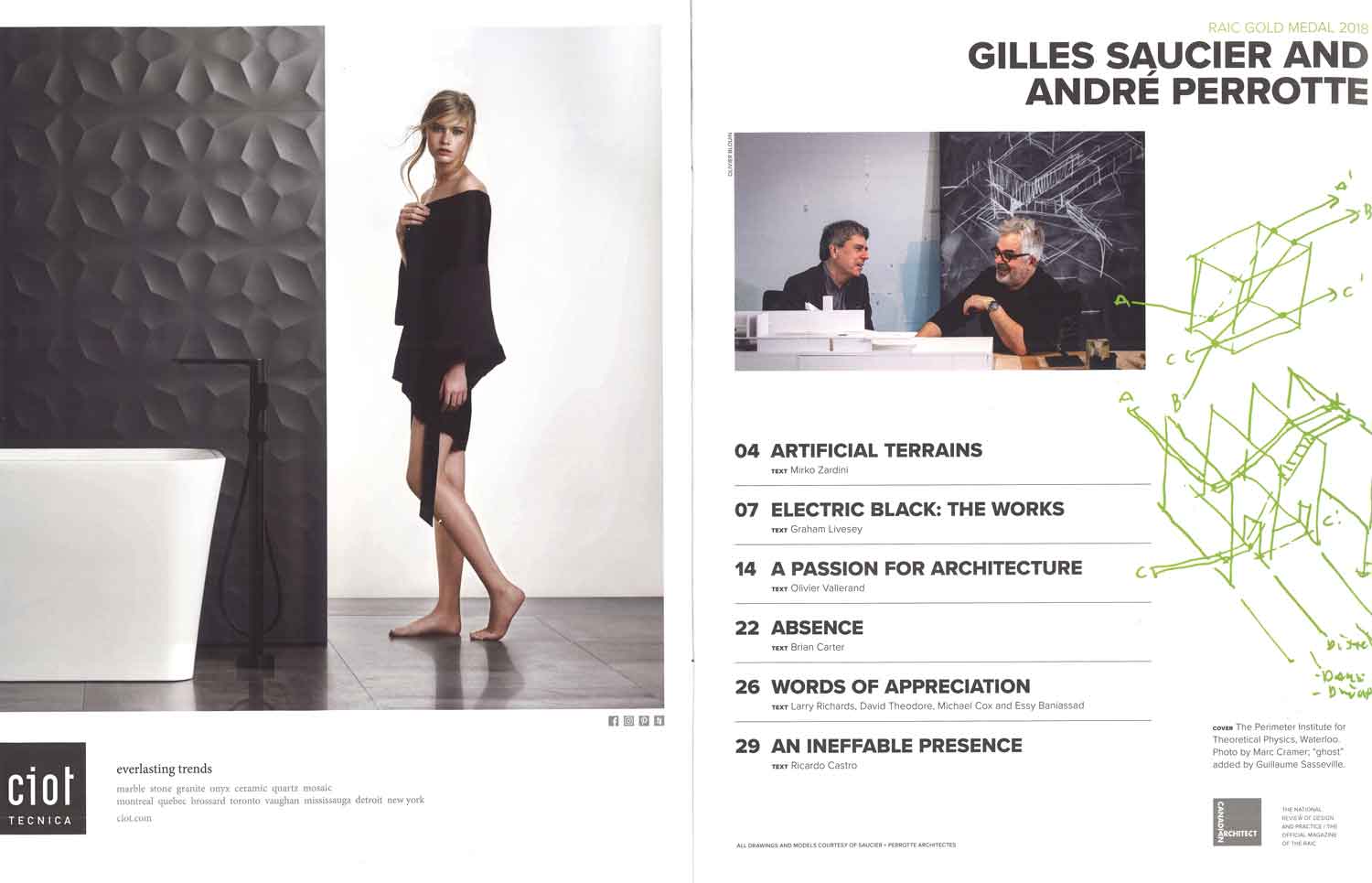

This exhibition does that by looking at the ways women were depicted in advertisements that appeared in Canadian architectural magazines and journals published between 1950 and 1975. By examining this visual imagery, we can better understand how the architectural profession perceived women. The print advertisements you will encounter in this exhibition may not appear to be as explicitly sexist as the advertisements we know from this period, but they communicate both subtle and not-so-subtle messages about a woman’s place within the profession. Viewing these advertisements, one thing is made clear: men are the architects, designers, and builders, while women are relegated to performing traditionally “feminine” tasks, or their bodies used only to sell products.

Today, women are entering the architectural profession in higher numbers. In Canada, women make up more than half the graduates of architectural master’s programmes, but still obtain only 29 per cent of the jobs in the field. However, it is crucial to note that there are still many women, particularly Indigenous women, women of colour, and women with disabilities, whose voices are even less prevalent within the profession.