Biography

“At his most charming A.J. looked uncannily like Peter Sellers, and like Sellers, could convey the sense of being almost anybody.1”

Jim Donahue Jr.

In 1917, Arthur James Donahue was born to affluent parents in Regina, Saskatchewan.2 The records are inconsistent; it seems he was known to friends as A.J., Jim, and James.

Donahue’s early life was marked by tragedy and privilege. His father died when he was very young, and he was only eleven when his much-loved step-father also died.3 These early heartbreaks left Donahue with a hefty inheritance which paid for the best schooling available in Regina, as well as one year spent at a boarding school in Switzerland.4

As a young man Donahue briefly attended the University of Regina before moving on to the University of Minnesota where he graduated in 1941 with a B.A. from the School of Architecture. Afterwards he was off to Harvard to pursue his M.A. in Architecture from the Graduate School of Design, having received a scholarship.5 He was the first Canadian ever to graduate from the program. While at Harvard, Donahue studied under famed Modernists Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, whose influence can be identified throughout Donahue’s entire career. He graduated in 1942.

Following his stint in the United States, Donahue considered a career change. He moved to Montreal and enrolled in an Arts and Science course at McGill University. He ultimately chose not to complete this degree, however it was during his time in Montreal that he met his future wife, Alice Bridget Donahue.6

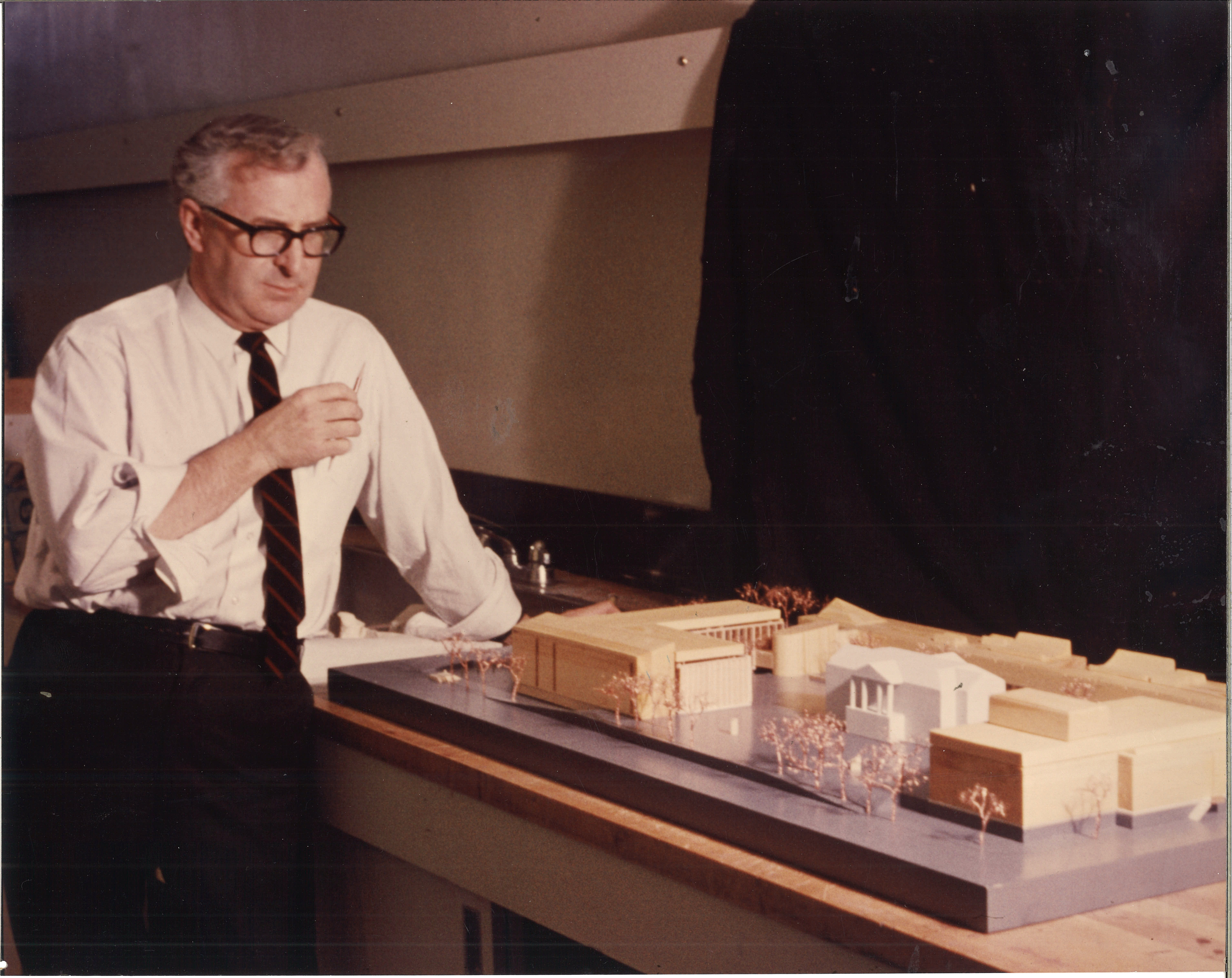

Donahue’s 1943 move from Montreal to Ottawa kicked off his career in earnest, a career which was in many ways emblematic of the post-war period. He quickly made a name for himself among Canada’s leading Modernist architects and Industrial designers, two fields experiencing intense growth in the wake of the Second World War. His tenure studying under Gropius and Breuer, both of whom were pioneers of prefabricated housing, resulted in Donahue’s recruitment by the National Housing Authority in Ottawa to work on city planning and prefab housing research. The following year Donahue was appointed Director of Information Displays for the National Film Board, a role which saw him organize travelling exhibits displaying post-war Industrial design innovations.7

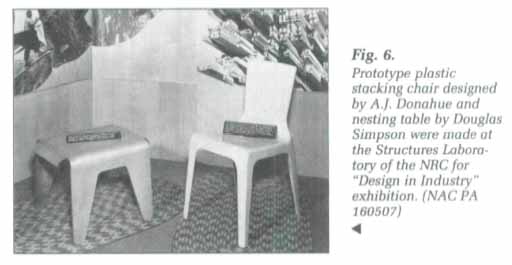

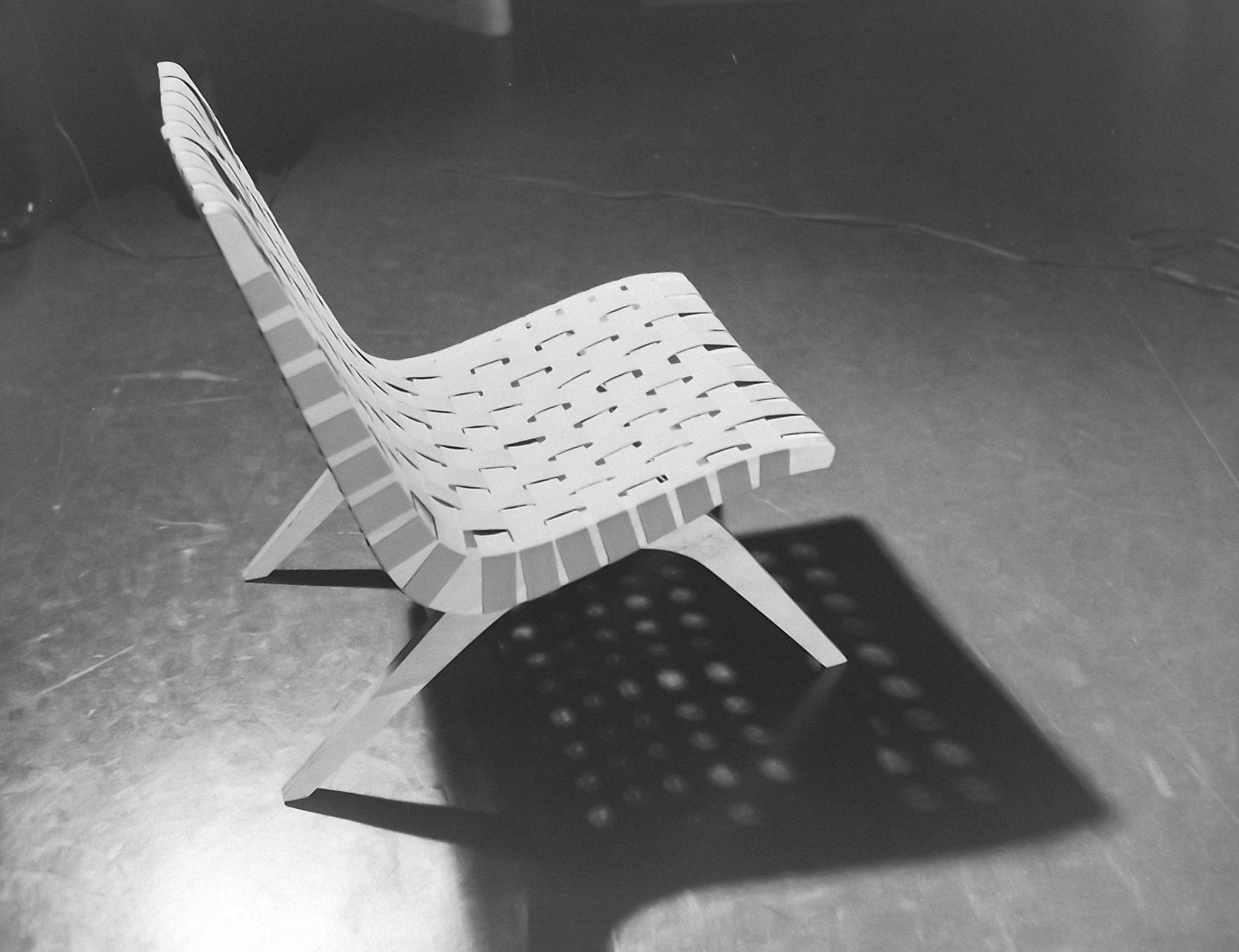

By 1945, Donahue had been hired by the National Research Council’s Building Research Division to conduct further research on prefab housing, as well as to work with materials newly developed during the Federal government’s recent war efforts. Donahue and his colleague Douglas Simpson worked with plastics, plywood, epoxies and aluminum to innovate on miscellaneous peace-time goods.8 Among the goods prototyped by Donahue and Douglas was the first-ever plastic chair, a light-weight stackable auditorium chair moulded from a single piece of plastic. This period is perhaps when Donahue discovered his life-long love for designing furniture.

Also in 1945, Donahue returned to Montreal to marry Alice. The pair settled down in Ottawa and quickly had their first child together, James (Jim).

Donahue’s groundbreaking work for the National Research Council won him acclaim as an Industrial designer and led him to co-found the Affiliation of Canadian Industrial Designers (ACID) in 1946. That same year, his reputation got him head-hunted for an Associate Professorship by John A. Russell, the Director of the University of Manitoba’s School of Architecture and Fine Arts. And so, he moved to Winnipeg!

Winnipeg offered Donahue a rich working life; the mid-twentieth century was a period of architectural revitalization for the city and Winnipeg was a particular stronghold of Modernism, Donahue’s signature style. His teaching career was a success; his students remembered him as a “dynamic and challenging lecturer.” His lecturing was in fact so sought after that he was invited to speak at the University of Minnesota, the Institute of Design in Chicago, and Notre Dame University.9 At the beginning of his time at the University of Manitoba, he worked with K. C. Stanley to create the interdisciplinary Planning Research Centre. Soon afterwards, the Faculty of Architecture experienced an enrollment boom which Donahue helped to navigate through his contributions to the 1957 Campus Design and Planning Committee.10 In his capacity as Associate Professor, Donahue travelled to Ottawa to serve as the University of Manitoba’s representative at the National Industrial Design Council.11

While living in Winnipeg, Donahue’s working life was not limited to his role at the University - his architectural career was in full swing. Privately, he designed two apartment buildings, three warehouses, and twenty homes across the city. By the late 1950s, he often partnered with the architectural firm Smith Carter Searle to work on major projects, including a failed bid to design the new City Hall and the acclaimed Monarch Life Assurance building at 333 Broadway Avenue. Also throughout the 1950s, Donahue served consecutive terms on the council of the Manitoba Association of Architects; his co-councillors included famed local architects Ernest J. Smith, Cecil N. Blankstein, and Dennis H. Carter.

By the 1950s, Donahue and his wife Alice had welcomed two more children, Dan and Maria, and were living in the second of their two Donahue-designed homes (the first at 8 Fulham Crescent, the second at 301 Hosmer Boulevard). There had also been a brief stint wherein the family lived at 375 Wellington Crescent, an apartment building which was designed, built and owned by Donahue. According to Donahue's oldest son, Jim:

"Each of our moves was like a jump to the next planet of possibility. The cozy Wrightian nest of Fulham Crescent House was quite perfect enough for the kids’ early childhood. Hosmer House was a series of runways and uncluttered spaces, perfect for the rambunctious years of us kids and the ever-more demanding stresses of the young fifties professional career.12"

The Donahue home, wherever its address, was “a culturally stimulating household.” Family life was lively, and music was always playing. Donahue and Alice, according to their oldest son, were “rather inclined to challenge conventional thinking.”

Unfortunately, Donahue’s personal life was badly impacted by his struggle with alcoholism. Though for many years Donahue was able to keep the fallout from his alcoholism somewhat contained, eventually the severity of his drinking irreparably damaged both his personal and professional life in Winnipeg. In 1963, Donahue abruptly left. According to some, “he didn’t have a choice in the matter.13”

Donahue relocated to Halifax, taking an Assistant Professor position at the Technical University of Nova Scotia. The Director of the University, Doug Shanbold, was aware of his alcoholism, however Donahue’s reputation as a respected lecturer and student mentor caused Shambold to take a chance on him.14 While living in Halifax Donahue also continued to work as an architect, partnering on several projects with local firm Duffus, Romans, Single, and Kundzins Architects.15

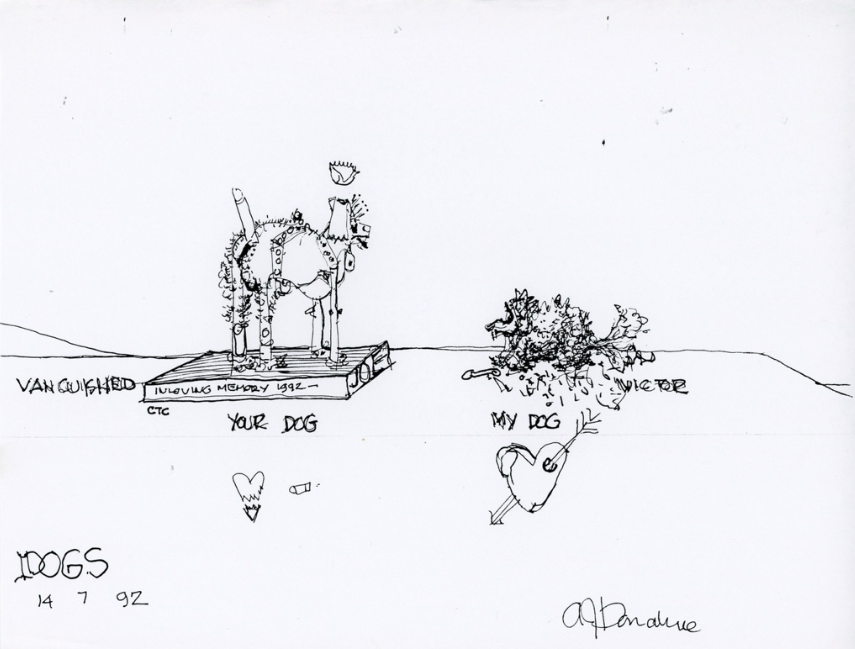

In 1976, poor health forced Donahue to resign from his position at T.U.N.S. This did not mark his retirement; that same year he began a working relationship with Keith L. Graham and Associates.16 Donahue moved to the village of Chester, Nova Scotia, where he remained for the rest of his life. During these years he moved within the community often, restoring three old houses and building one according to his own design.17 Donahue spent his final years expressing himself strongly through art. Anger at Chester’s municipal council, fondness for his maritime home, revisited designs for furniture and houses, and more abstract expressions are all among the themes present in the large catalogue of personal drawings created at the end of Donahue’s life.

Also at the end of his life, Donahue got involved in politics. In 1993, just three years before his death, he ran for office with the National Party of Canada, a short-lived anti-free trade political party. He (and the party) did not win.18

Donahue died at the South Shore Regional Hospital in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia on February 4th, 1996. He was 77. His life partner at the time of his death was Helena Marks.19

Donahue was remembered fondly by his former University of Manitoba student and colleague Douglas Gillmor as a funny person with a gift for story-telling, who was fun to be around.20 Dennis Carter, for whom Donahue served as a consultant while living in Winnipeg, remembered his work ethic and intensity, as well as his fearlessness in experimentation.21 Although he only spent 17 of his 77 years in Manitoba, their significance to his career and reputation cannot be understated. Donahue has been called “easily the best architect of the Modern period in Manitoba and perhaps in Canada,” and it has been said that he “was charged with the task of bringing the gospel of Modern to the prairies.22”

Dad had a productive life and a pretty long one, with many troubles along the way. The AJ I last spoke with was a pretty happy and creative guy back home in his maritime environment of Nova Scotia.23

Jim Donahue Jr.