Foreword

Ryan Takatsu, May 17 2023

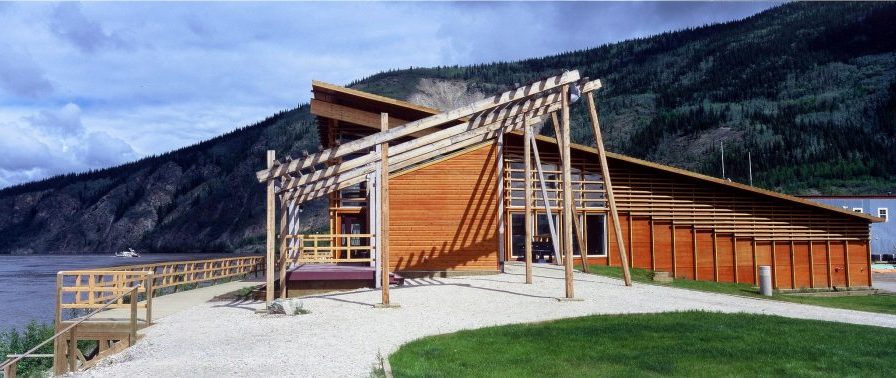

In September 2019, I contacted the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation regarding the inclusion of the Japanese-Canadians architects, designers, builders and contractors who contributed to Manitoba’s built environment.

On January 16, 1942, due to repercussions of World War II, the War Measure’s Act enforced the internment of almost 22,000 Japanese-Canadians. The consequences were devastating. Property, businesses, community, and livelihood were appropriated and lost. All Japanese-Canadians were evacuated, primarily in British Columbia. They lost their democratic rights and freedoms as Canadian citizens. One hundred and eighteen of those interned arrived in Winnipeg on April 13, 1942 and then relocated to various communities in southern Manitoba to work as forced labourers on the sugar beet farms. Soon after the war ended and the restrictions were finally lifted in April 1949, many of the families moved to Winnipeg to rebuild their lives and community. There was a loss of identity, culture, and language for the younger generation. The internment experience was everlasting and emotionally hurtful.

Due to lost education and employment opportunities as a result of the war, many returned to school to study (or apprentice in) architecture, design and building trades. The post-war economic and population growth of Winnipeg created a building boom. This set of circumstances made it possible for Japanese-Canadians to thrive as contractors, home developers, architects and designers.

In September 1988, the federal government of Canada acknowledged the social-economic injustices endured during and after the World War II. The redress and formal apology became a reality.

April 2022 marked Gaman (Honouring the Survivors), the 80th anniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese-Canadian internments to Manitoba. The Buddhist phrase, Gaman (我慢) means “enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.

The Japanese-Canadian experience was a long difficult journey of a world war, systemic racism, internment, and relocation. This project acknowledges the importance of the contributions made by Japanese-Canadian to Manitoba’s built environment.

I wish to thank Susan Algie for making this project possible, and to researchers and writers Alexander Gowriluk and Catherine Acebo for documentation.