Introduction

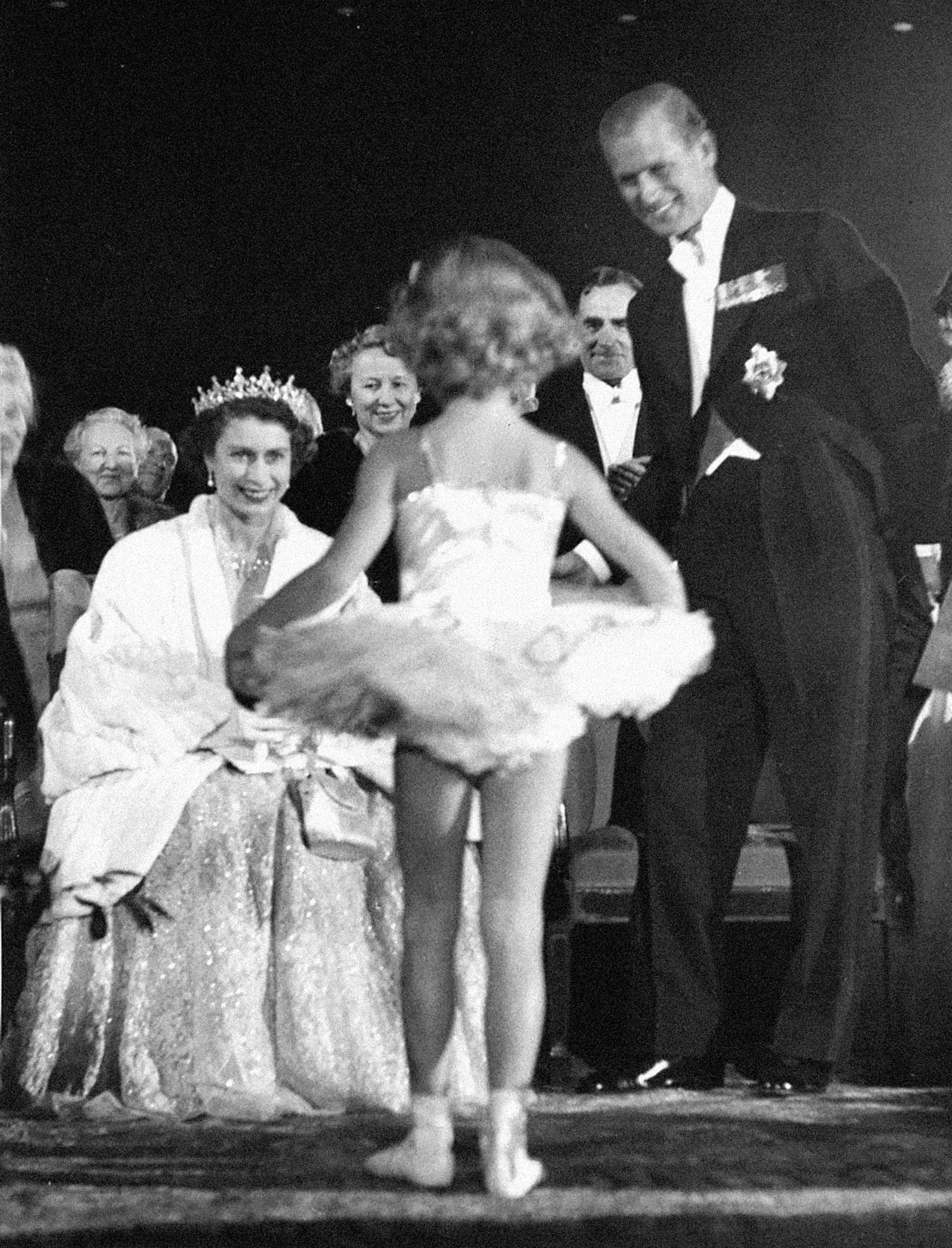

Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was Queen of Canada, the United Kingdom and 14 other Commonwealth Realms for 70 years. She toured Canada more than any other country outside of the United Kingdom, visiting Winnipeg more often than Paris or Washington, D.C. Queen Elizabeth granted the first Royal designation of her reign to the Royal Winnipeg Ballet in 1953, and one of her last to the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada in 2014. Her Majesty’s fondness for Winnipeg went beyond Royal tours or designations and her connections to the city and its people will remain.

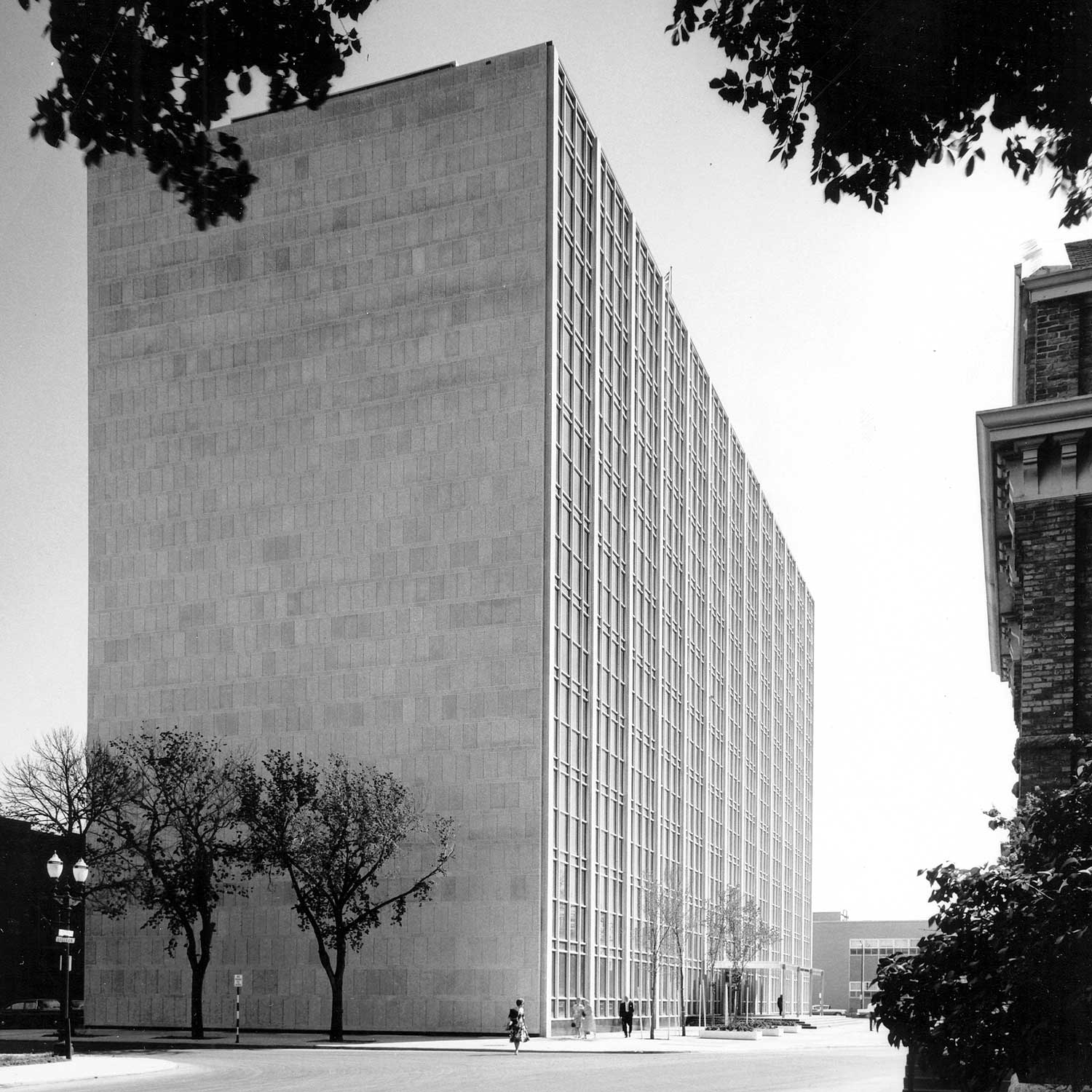

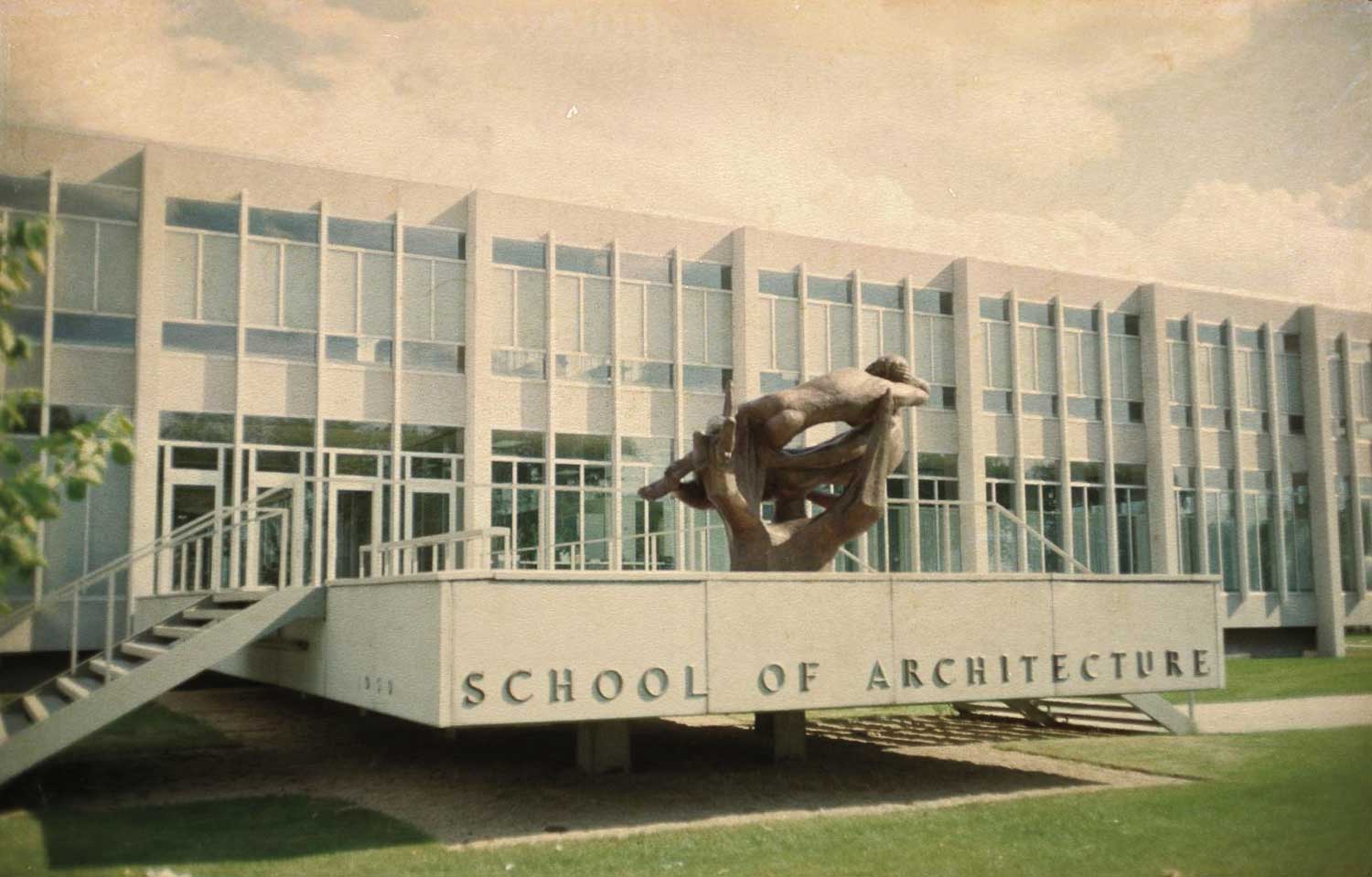

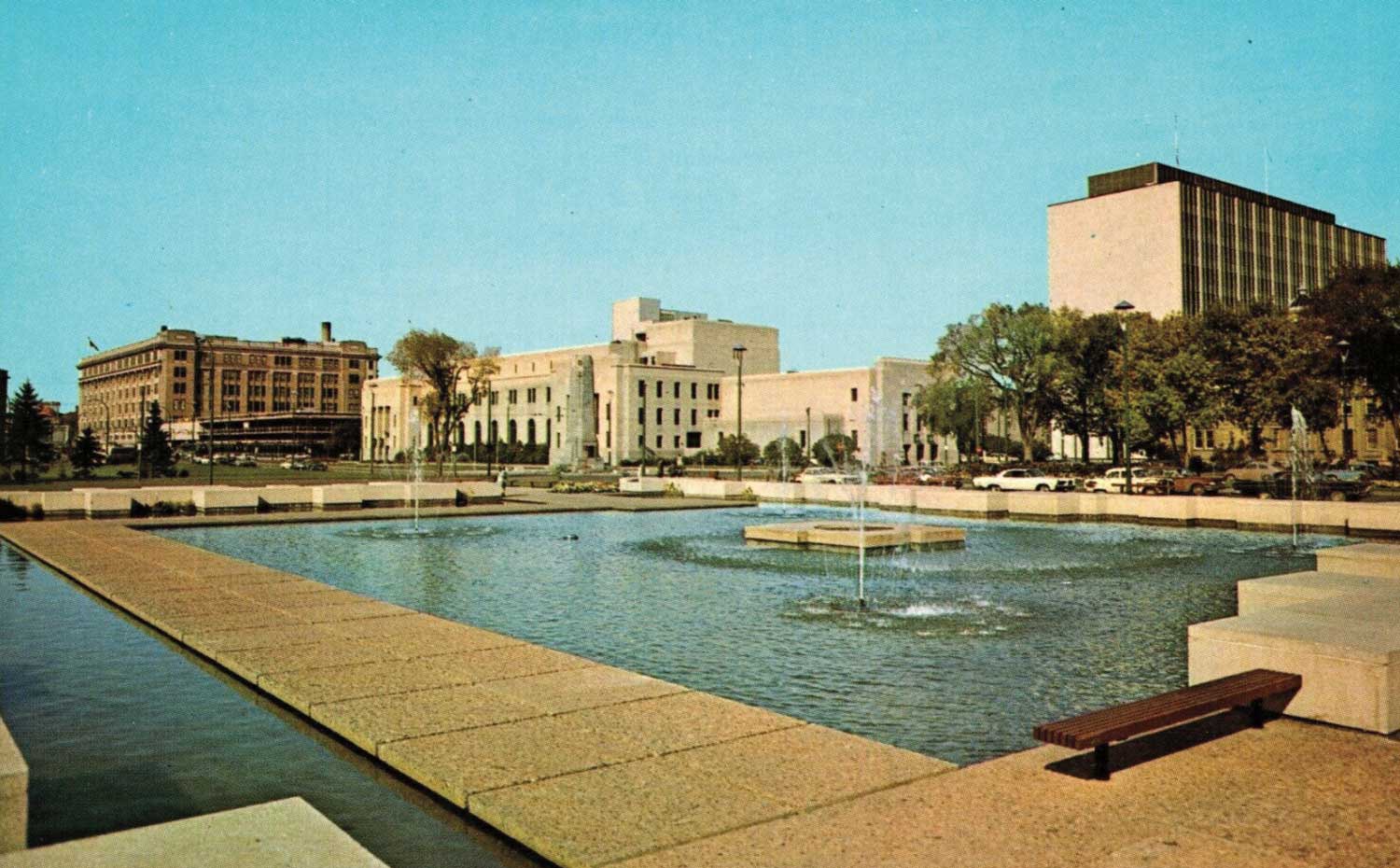

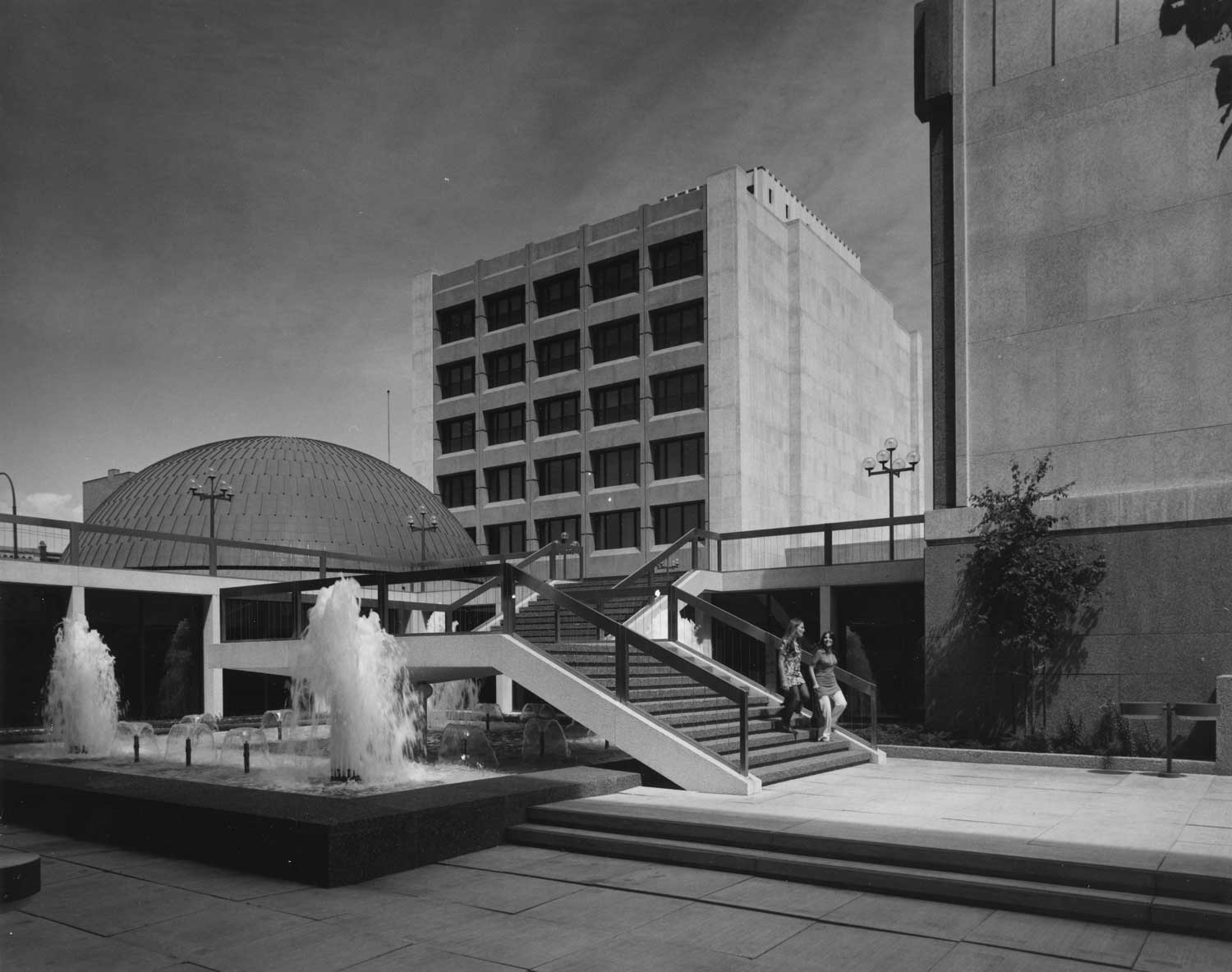

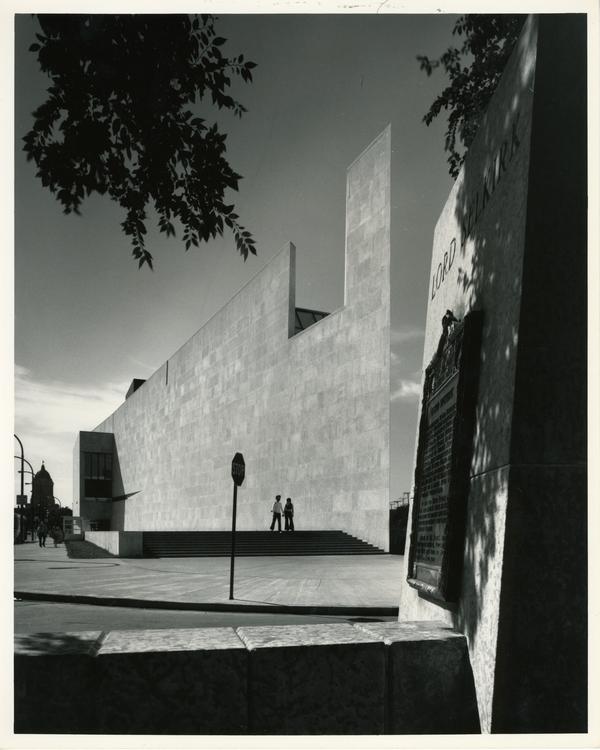

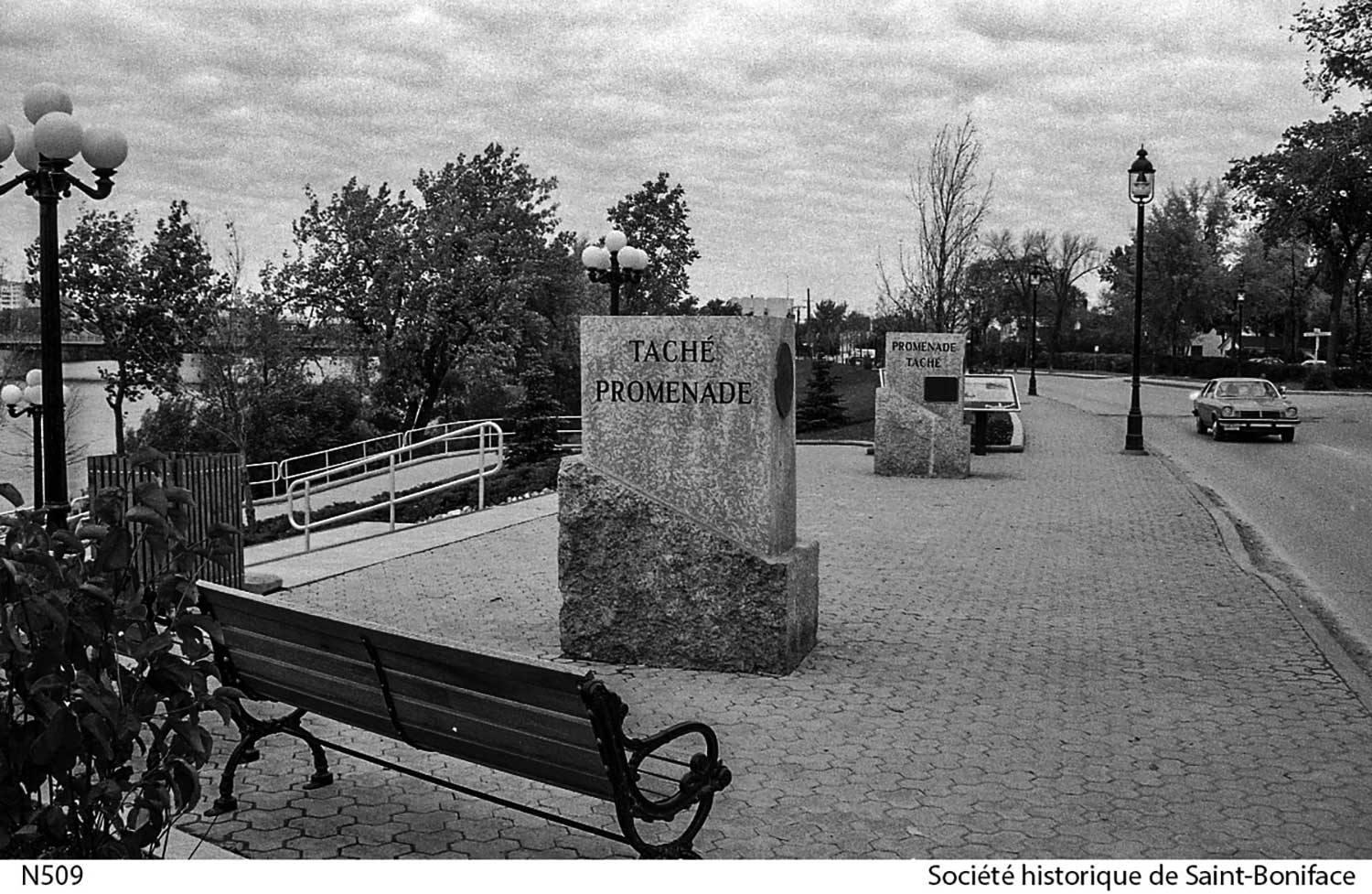

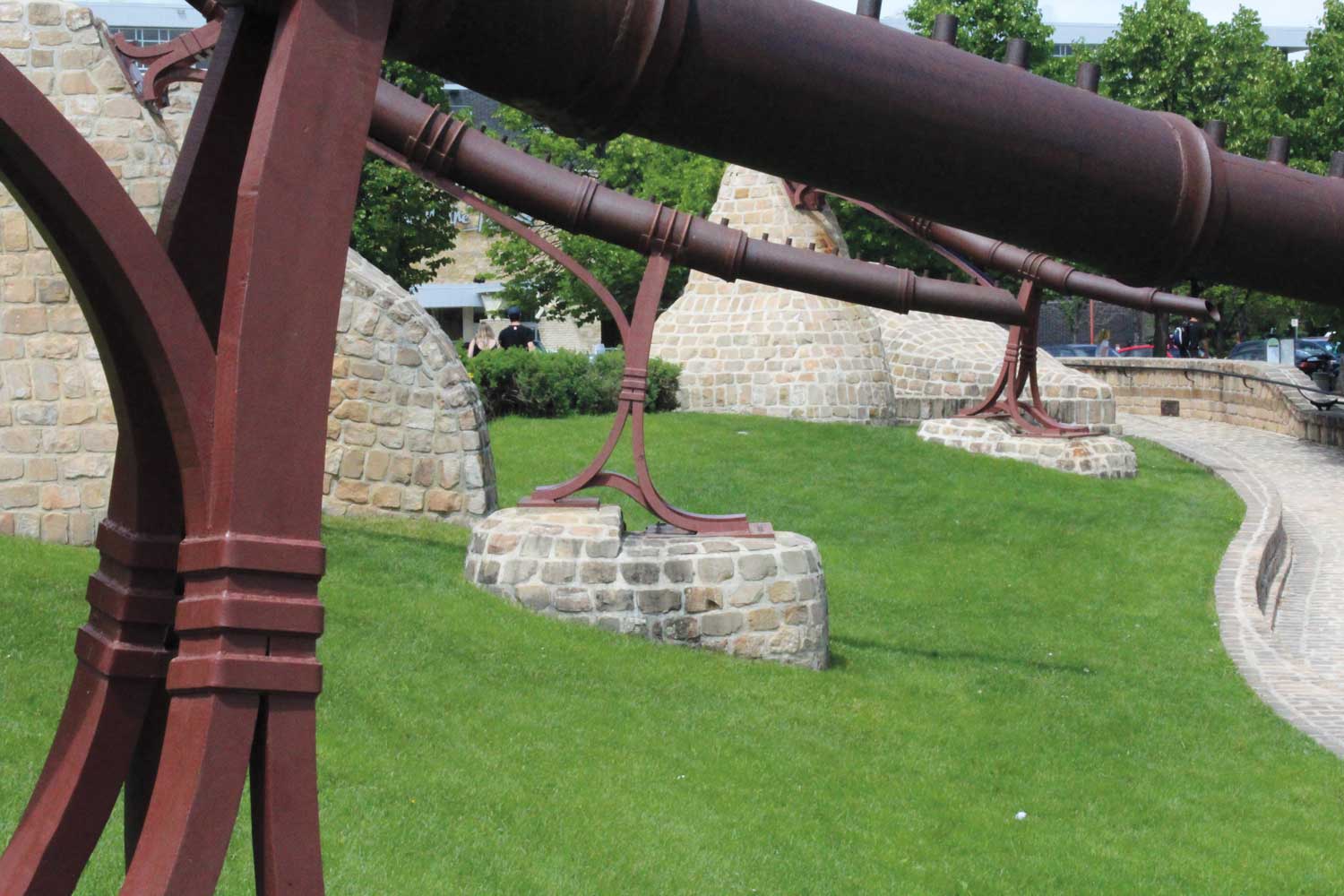

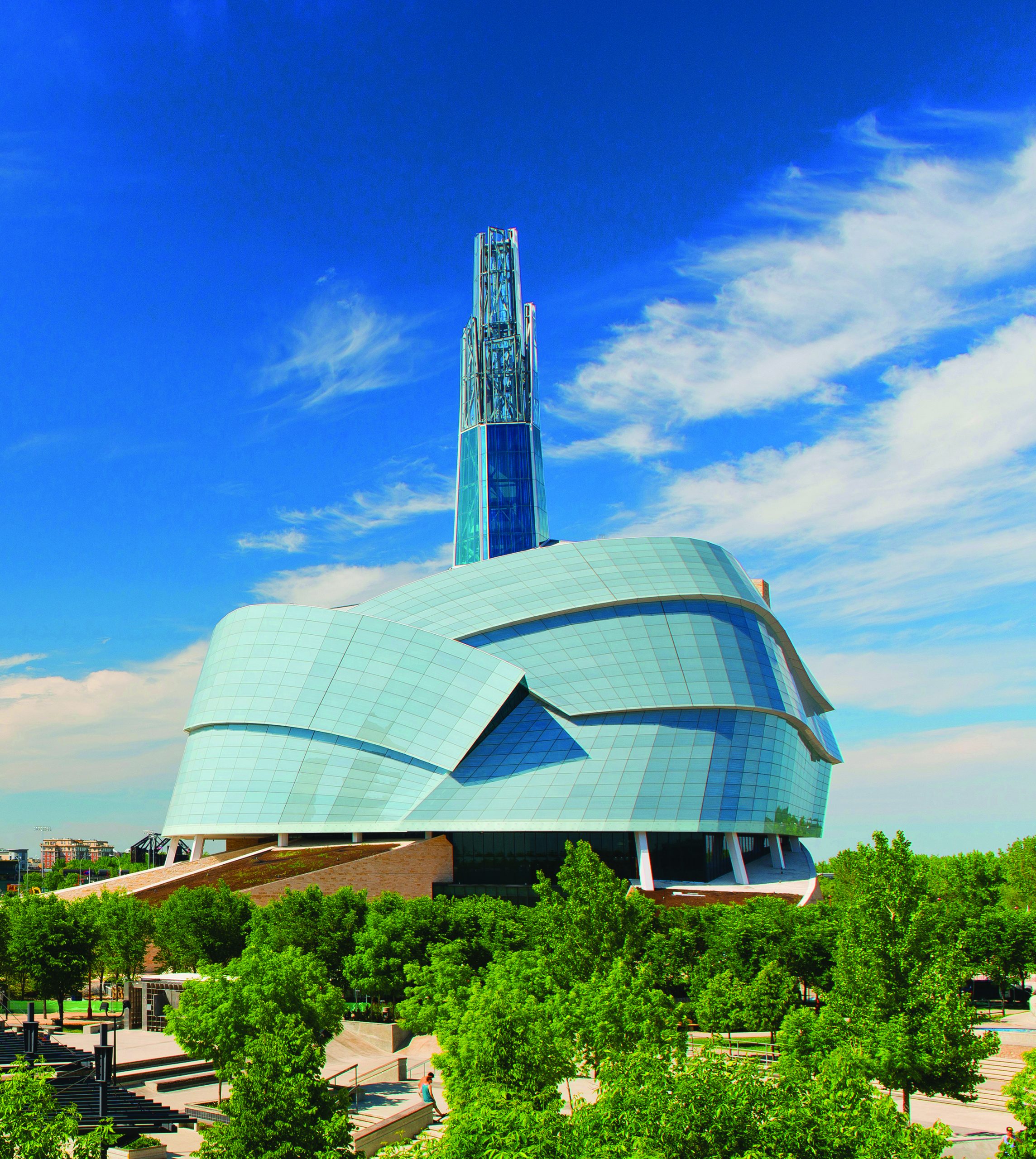

Queen Elizabeth’s reign is not defined by a single architectural style, instead it reflects Winnipeg’s emergence as a centre of distinctly Canadian modern design. Innovations in technology and investments in education, health, and culture spurred dramatic change, including confronting historical legacies of colonization.

The ‘Gateway to the West’ has evolved into a thriving centre of arts and culture, renowned for its friendliness and diversity. Winnipeg’s unique architectural landscape, highlighted by impressive modern design and historical restorations, reflects 70 years of immense change—a modern Elizabethan Era.

"I have watched with admiration as familiar European traditions have been enriched by the deep spiritual cultures of the First Nations and by the entrepreneurial and artistic flair of newer communities, coming together in mutual respect…to produce a particular Canadian genius for altruistic openness and reconciliation, enterprise and creativity."

Queen Elizabeth, October 8, 2002

This exhibition was produced with support from the Government of Canada, Department of Canadian Heritage.