Roy Sellors and Church Design in the Postwar Period

As a prominent architect and professor at the University of Manitoba's Faculty of Architecture, Roy Sellors was instrumental in the development of Winnipeg's architectural landscape. In addition to producing an impressive body of work that includes residential homes and institutional buildings, he designed churches that reflected the rise of modernist architecture and the liturgical movement in the mid-twentieth century.

The Liturgical Movement and Modernist Architecture: Building New Catholic Churches

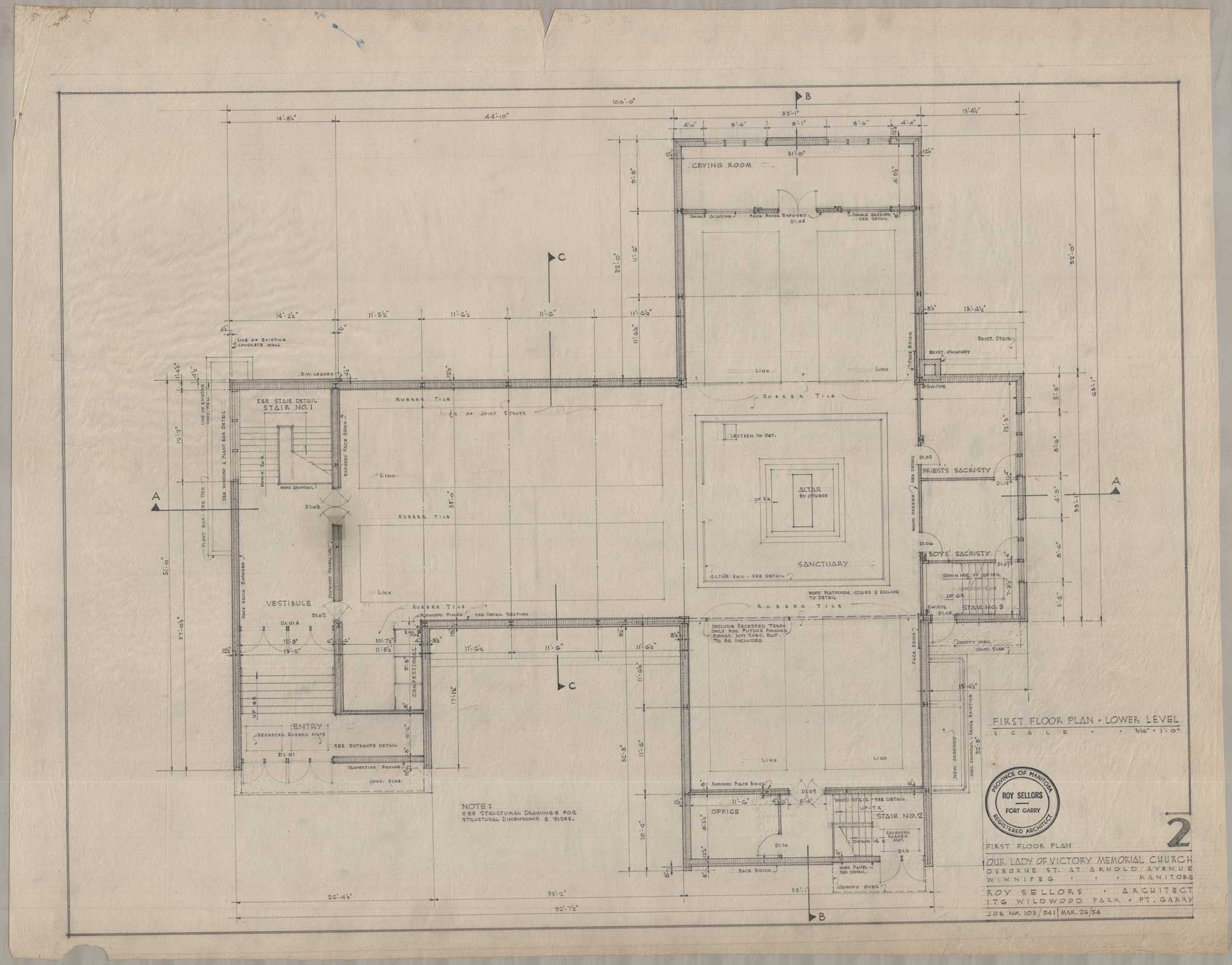

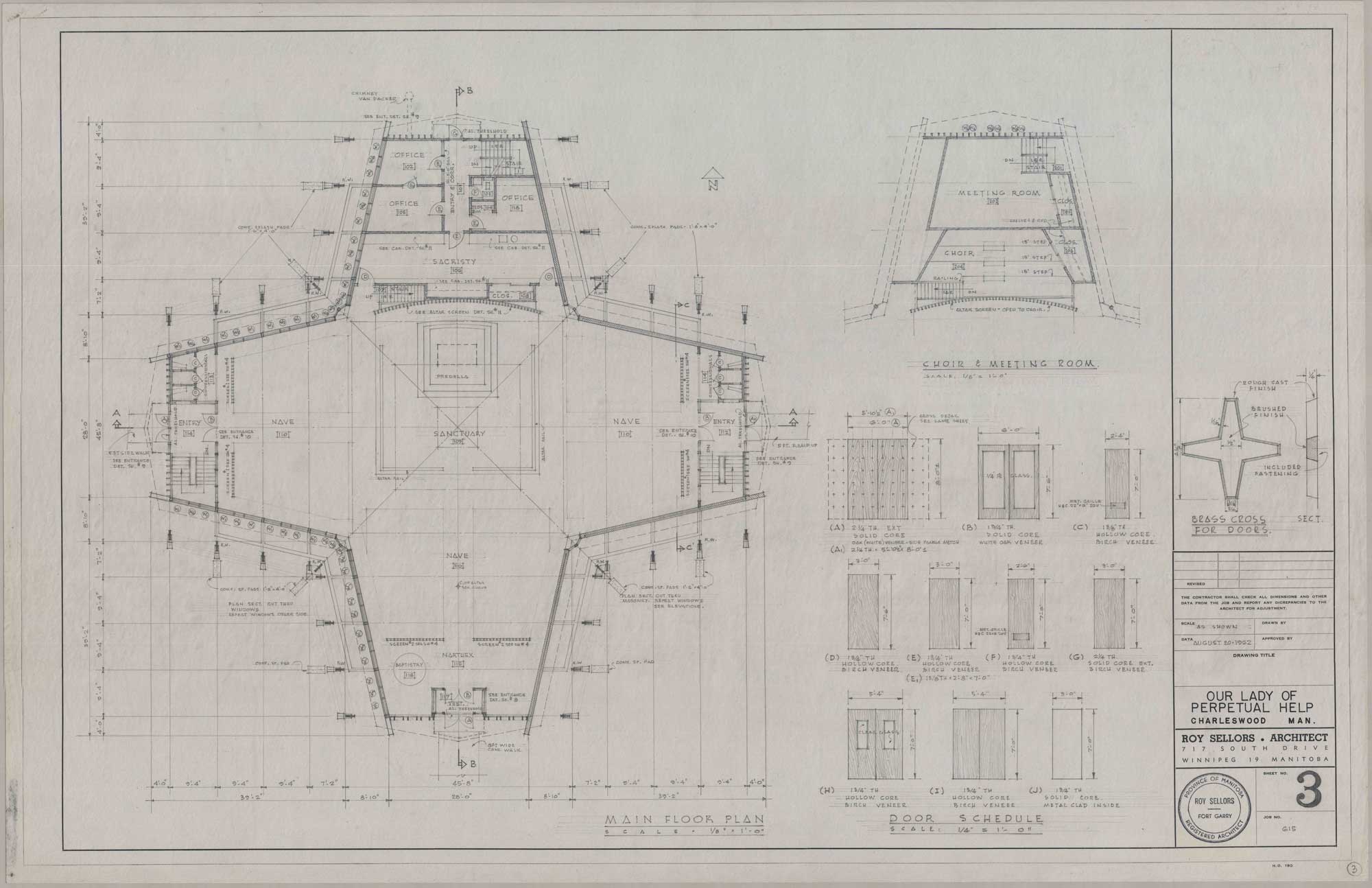

Since it was codified in the sixteenth century, the old liturgy set the parameters for building acceptable churches. Following these parameters, churches were designed with the intention of separating the congregation and the priest. This was done by using long basilica plans, separate chancels, and building altars with rails.

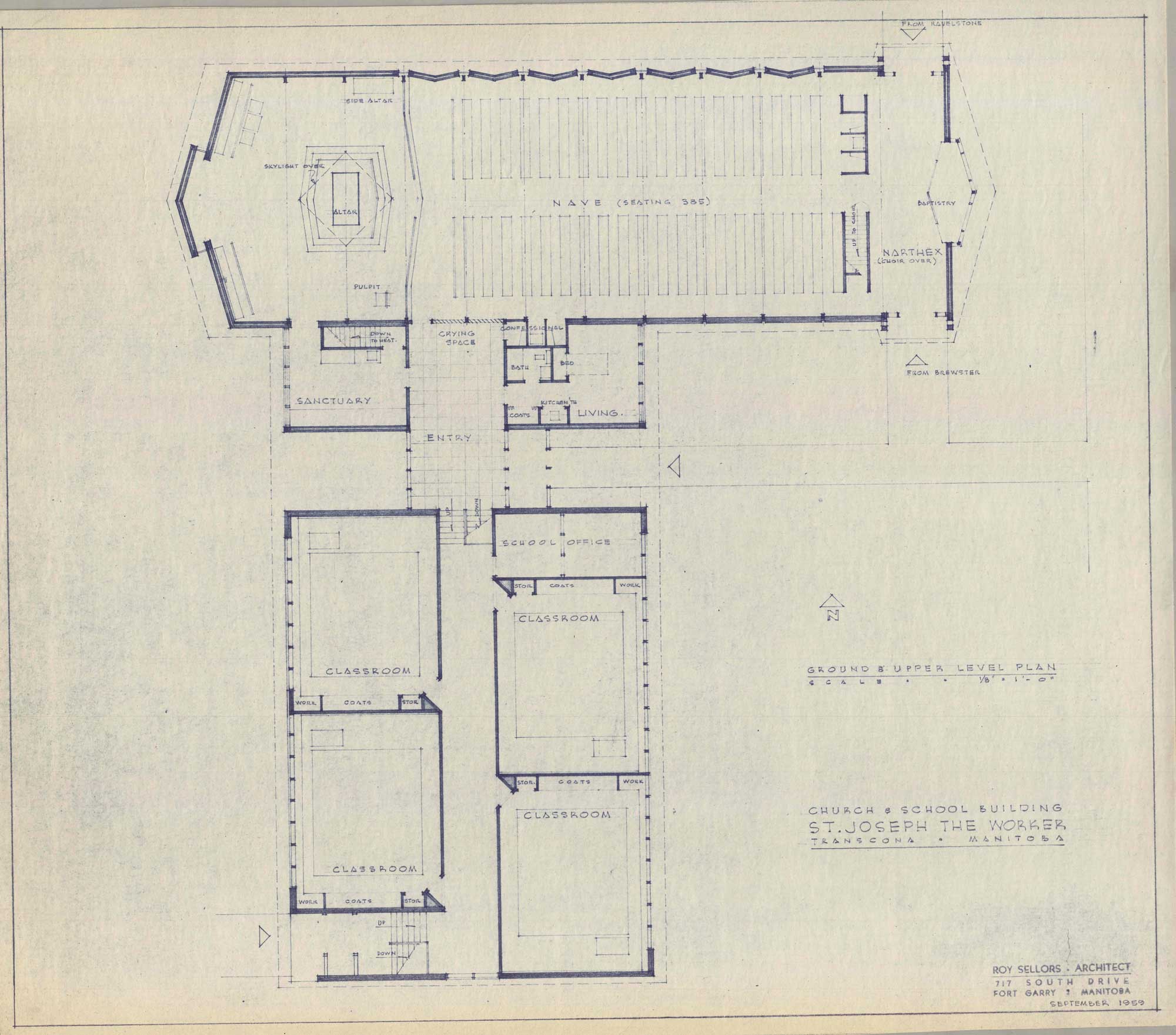

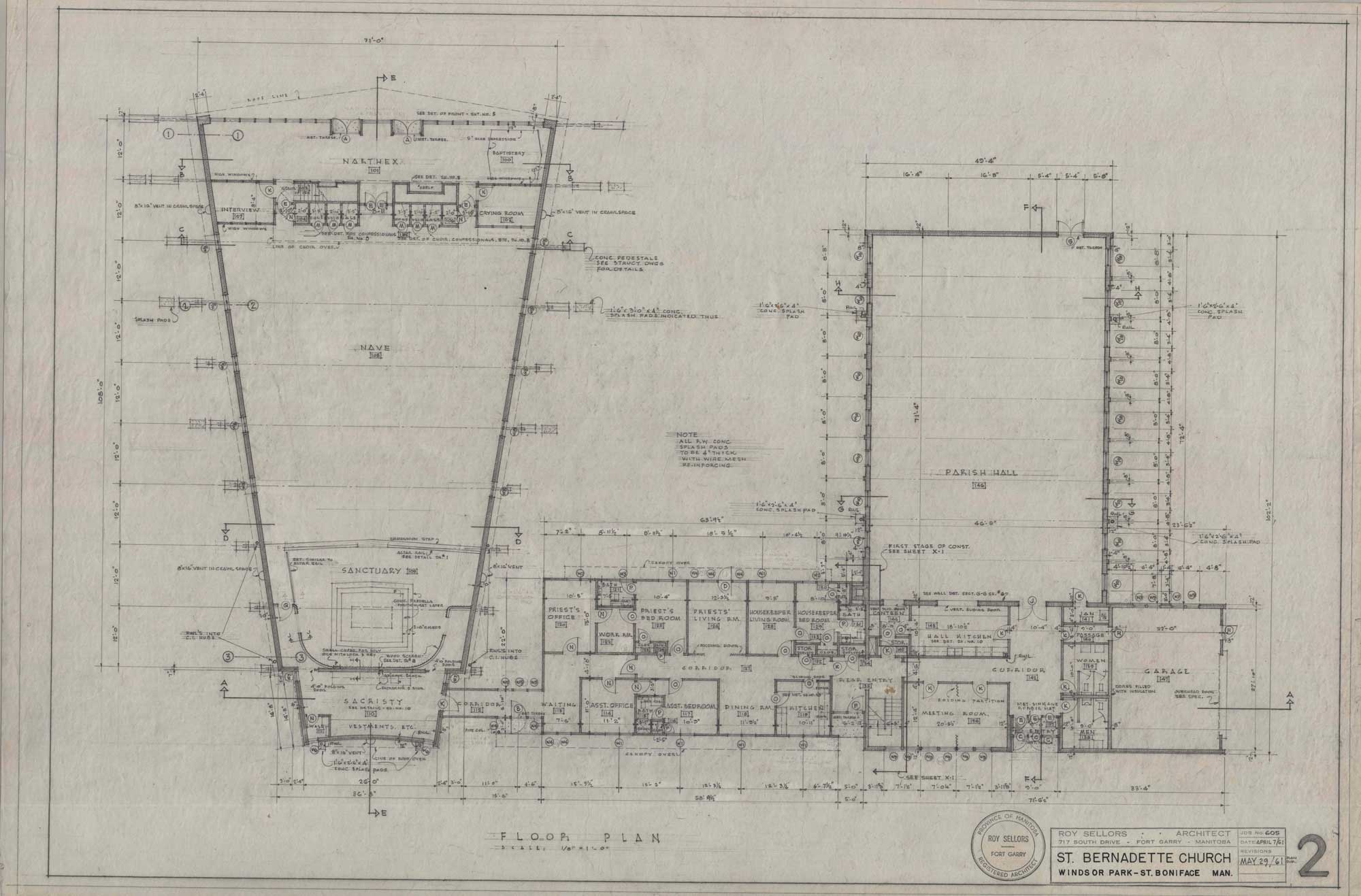

Inspired by theological scholarship about the original and more communal roots of worship, the liturgical movement pushed against the old liturgy's individualism and pursued more engaging expressions of faith. In the new liturgy, the priest faced the nave and communicated directly with the congregation. Whereas parishioners could only come as close as the altar's railing in the old liturgy, the new liturgy invited the congregation to enter the sanctuary to give readings and bring bread and wine to the altar in an offertory procession.

The liturgical movement gained more proponents in the postwar period. Parishes turned to modern architecture for the design of their churches because modern architecture better reflected the changing methods of worship. The liturgical movement's desire to strip away the inessential components of worship echoed the modernist movement's own interest in clear and ordered design.

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) addressed the shifting nature of worship and its implications on church design. In 1963, Pope XXIII officially welcomed innovative design and building techniques into sacred spaces. Sellors had already been using modern architecture to design religious buildings that communicated these shifting ideas.

The Impact of the Liturgical Movement in Sellors' Modernist Churches

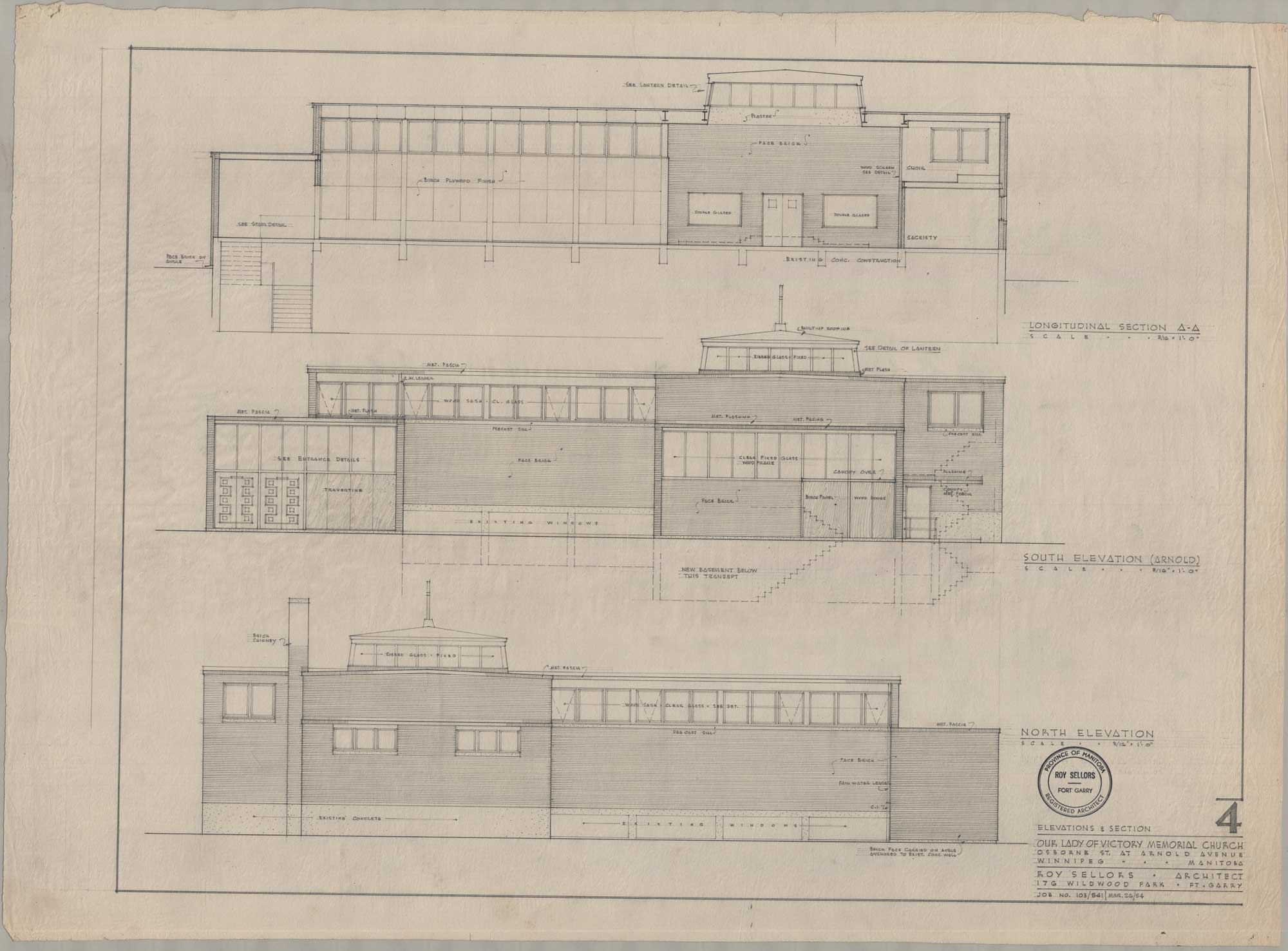

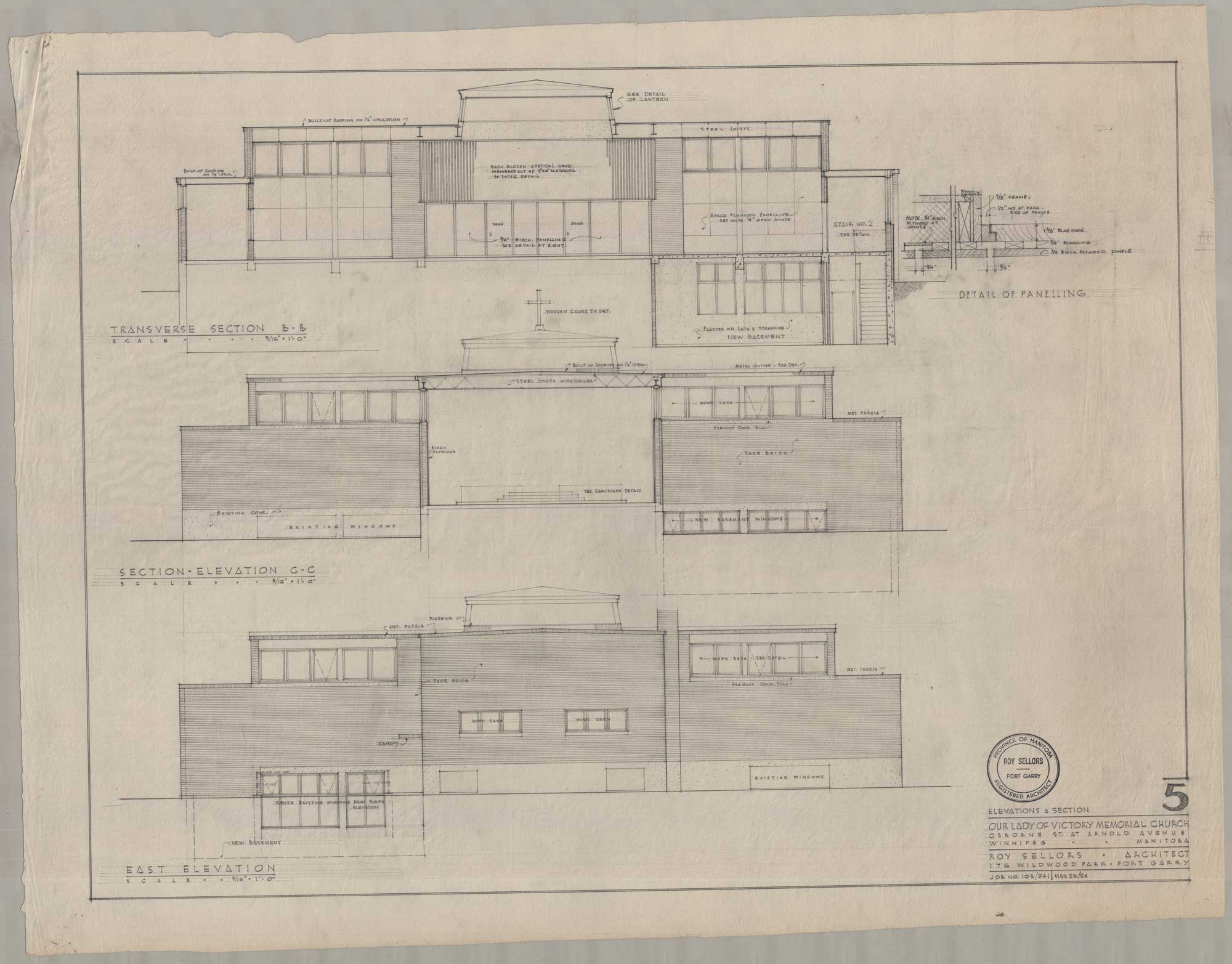

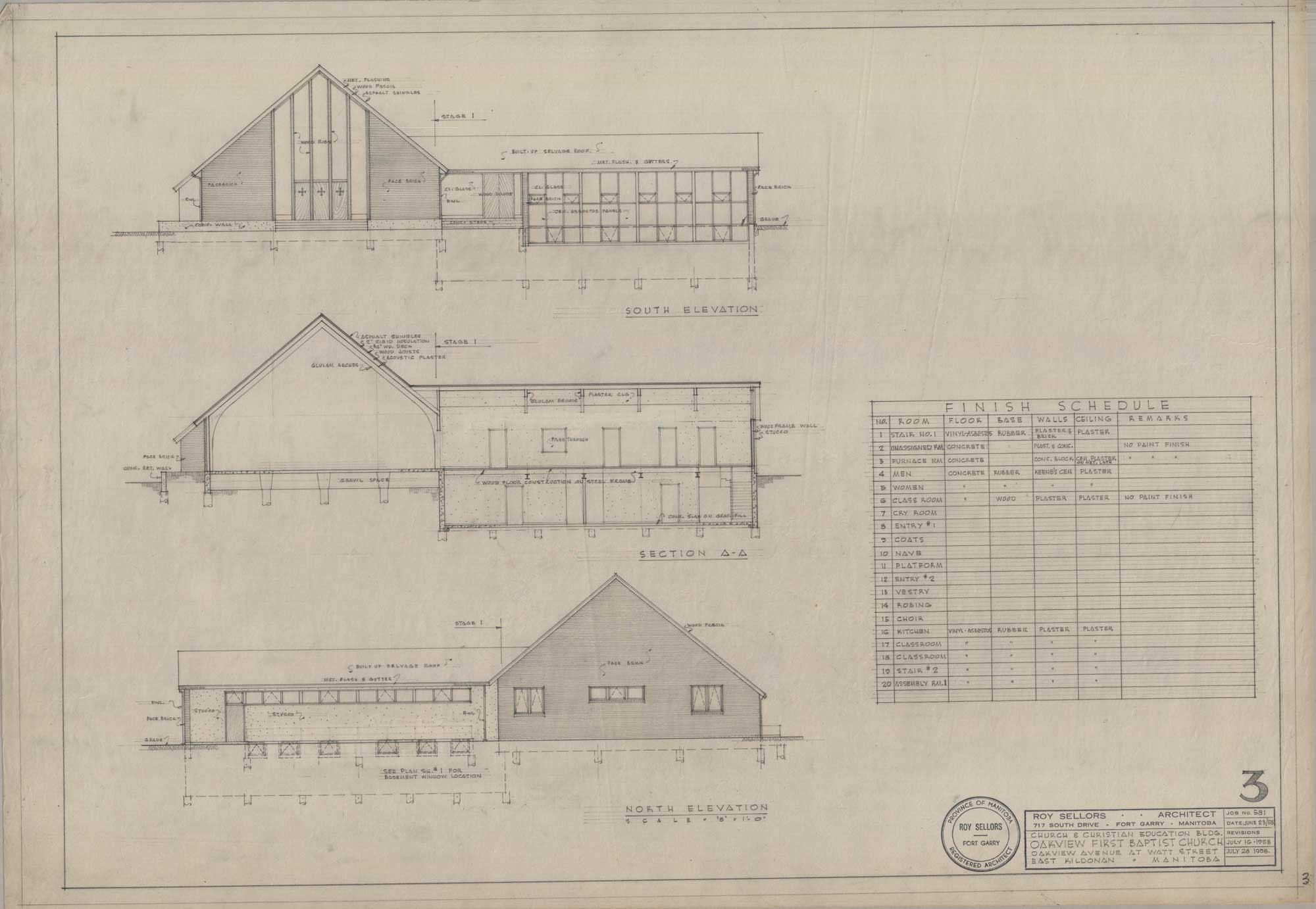

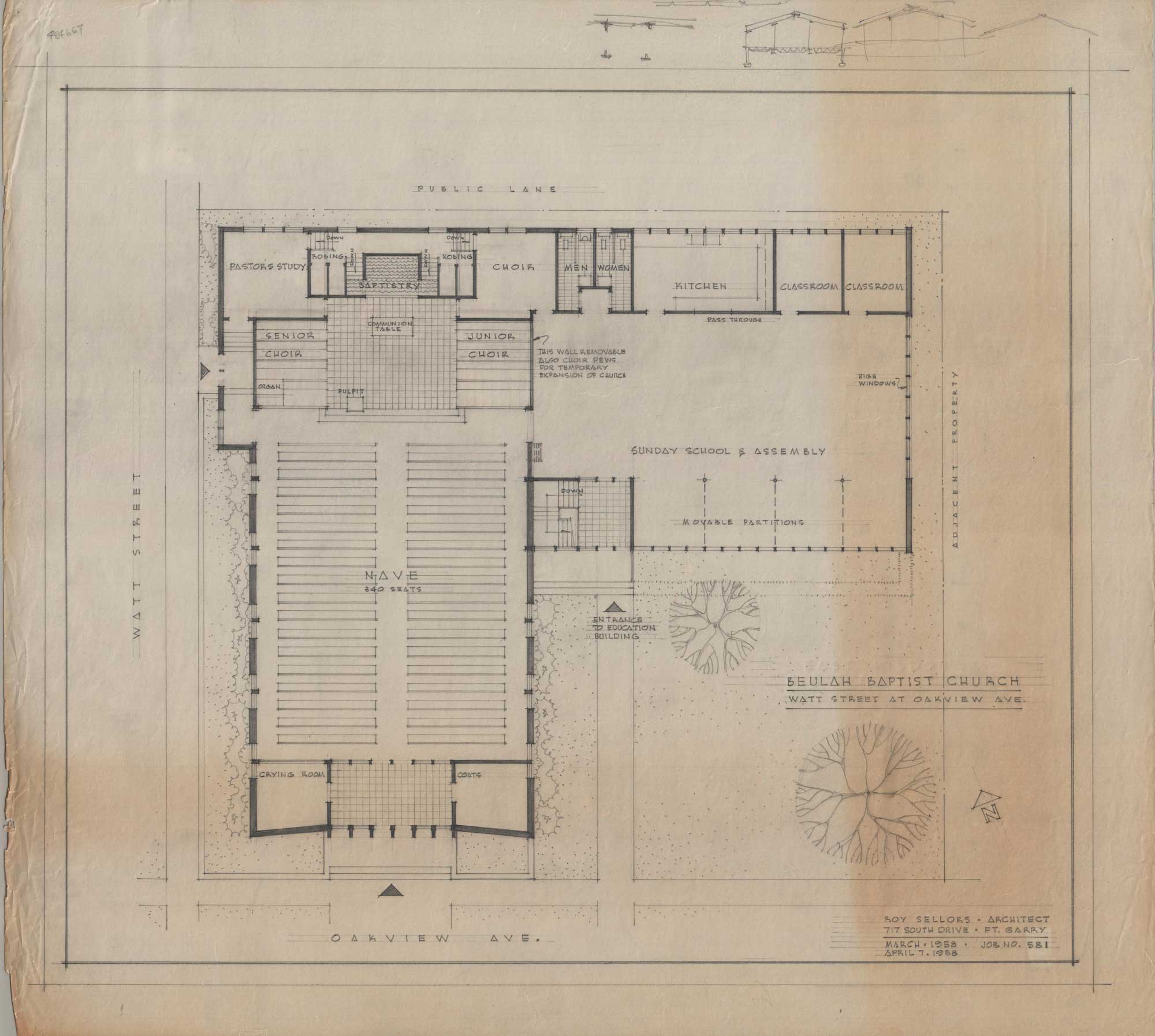

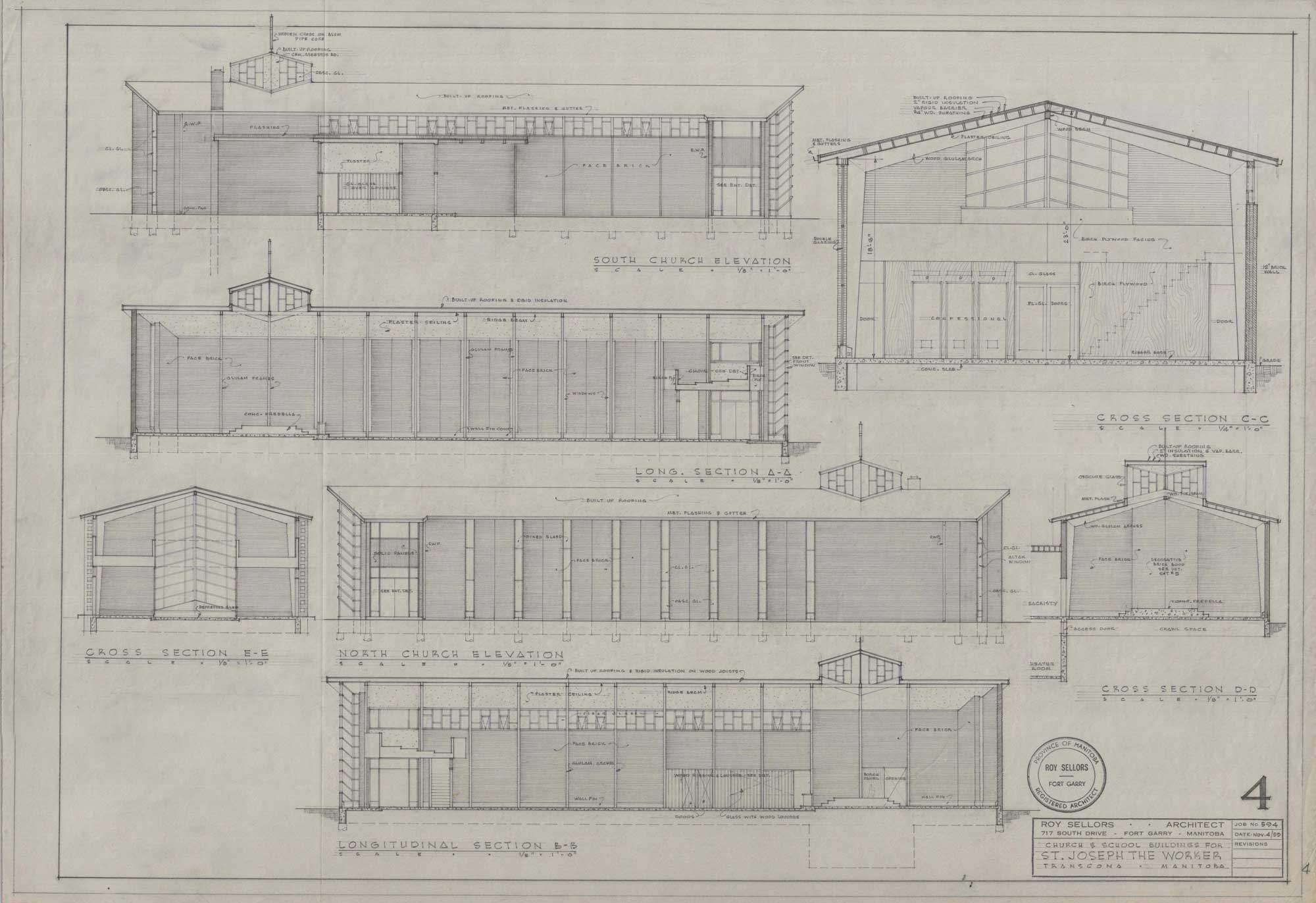

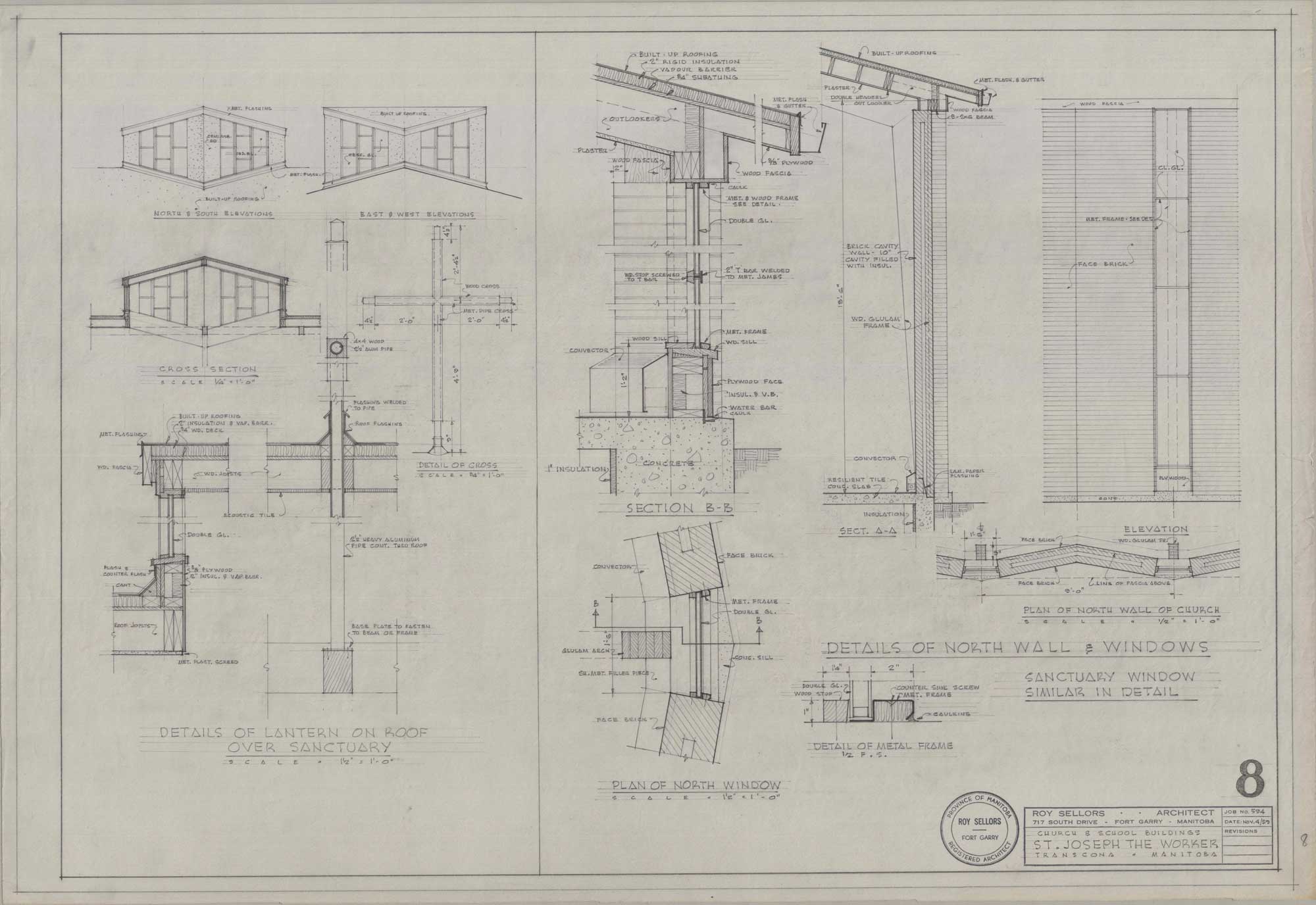

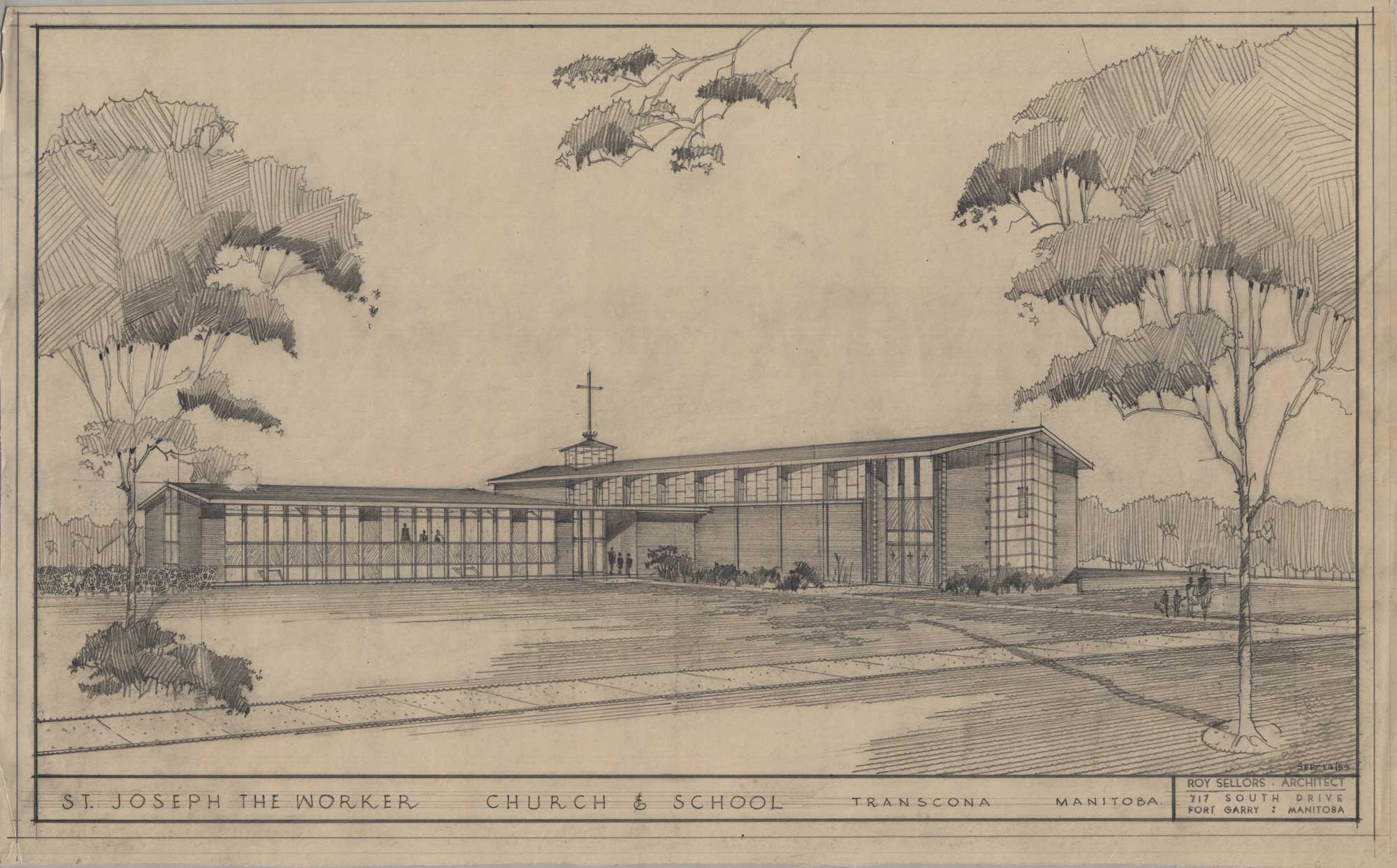

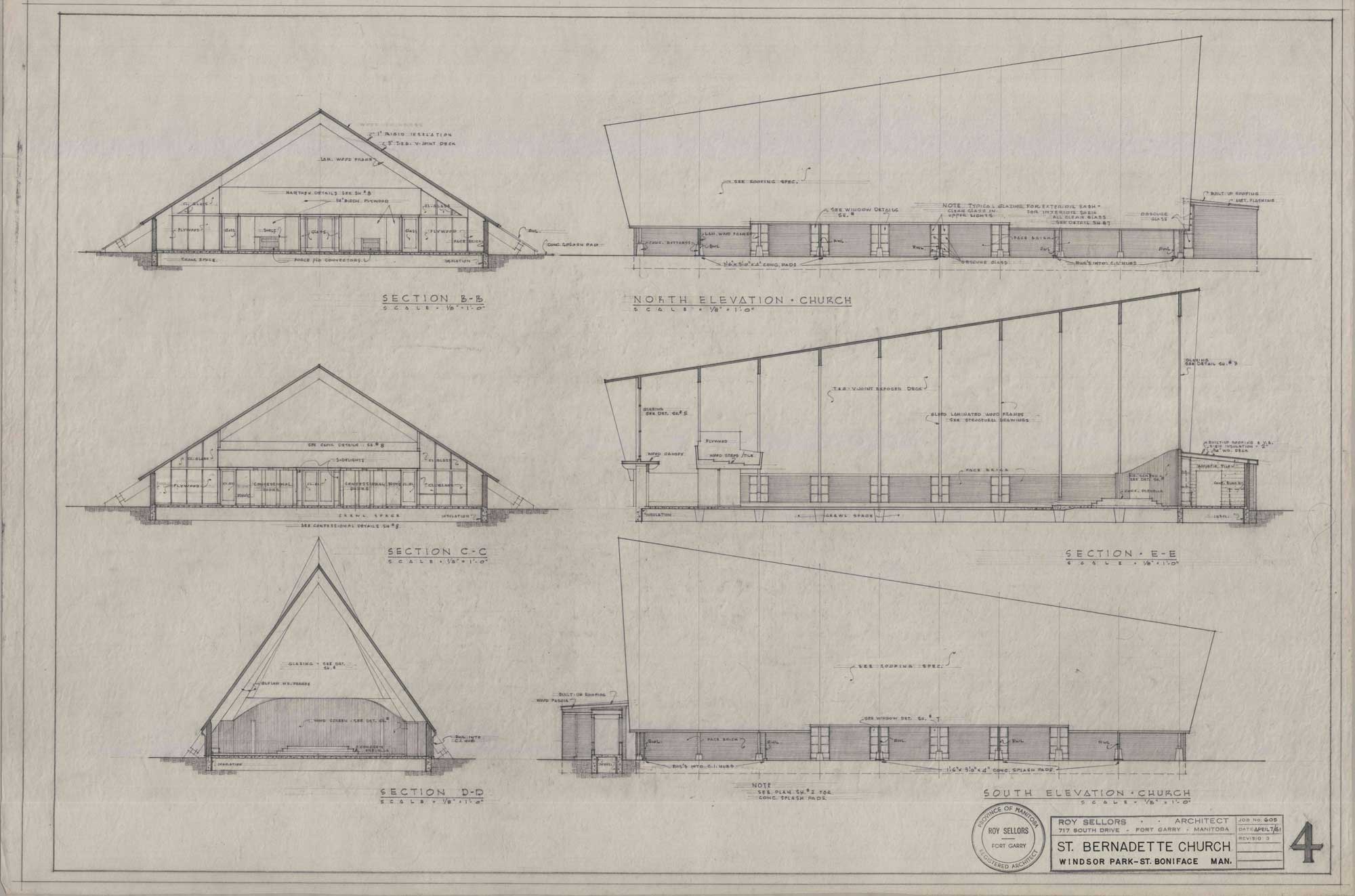

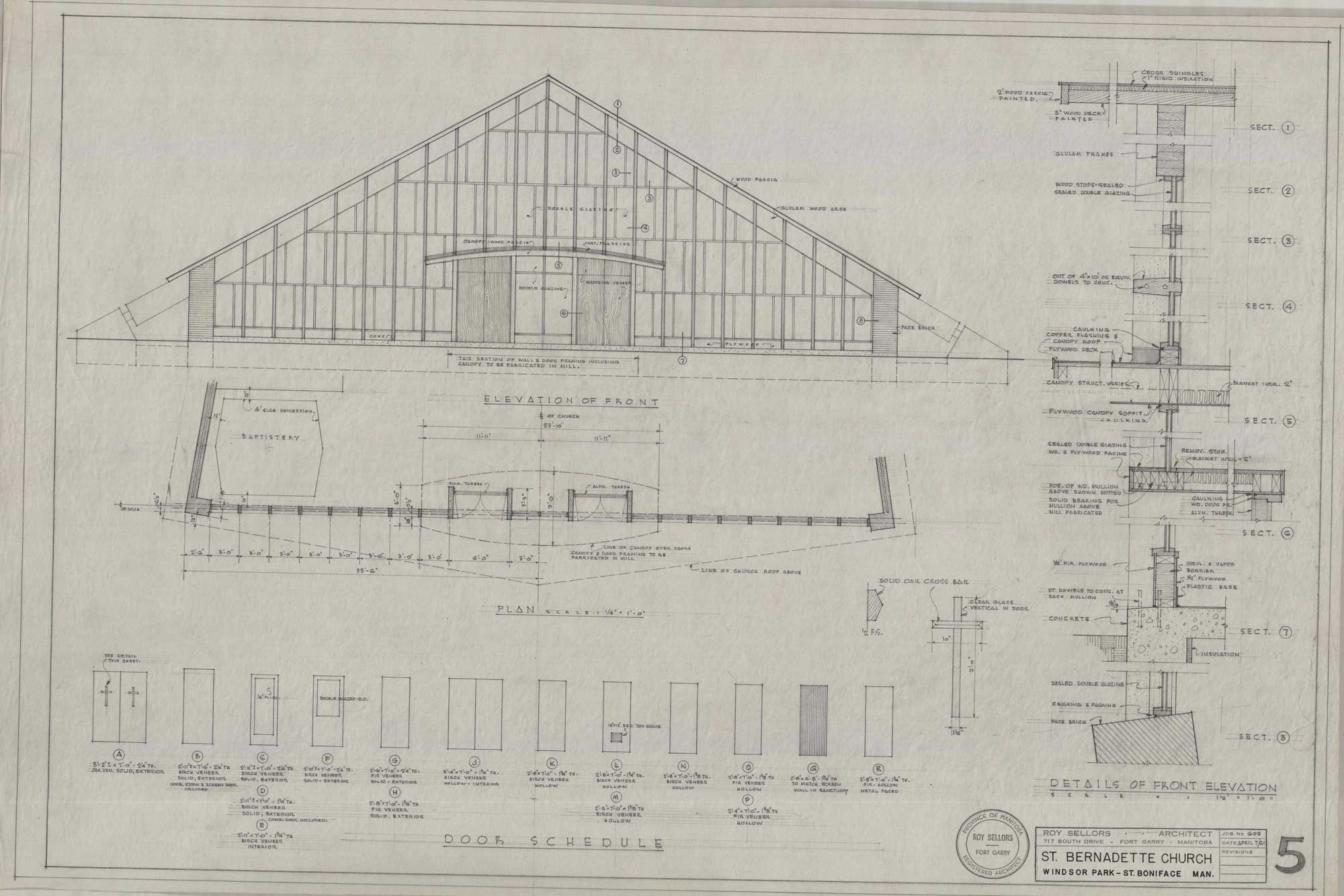

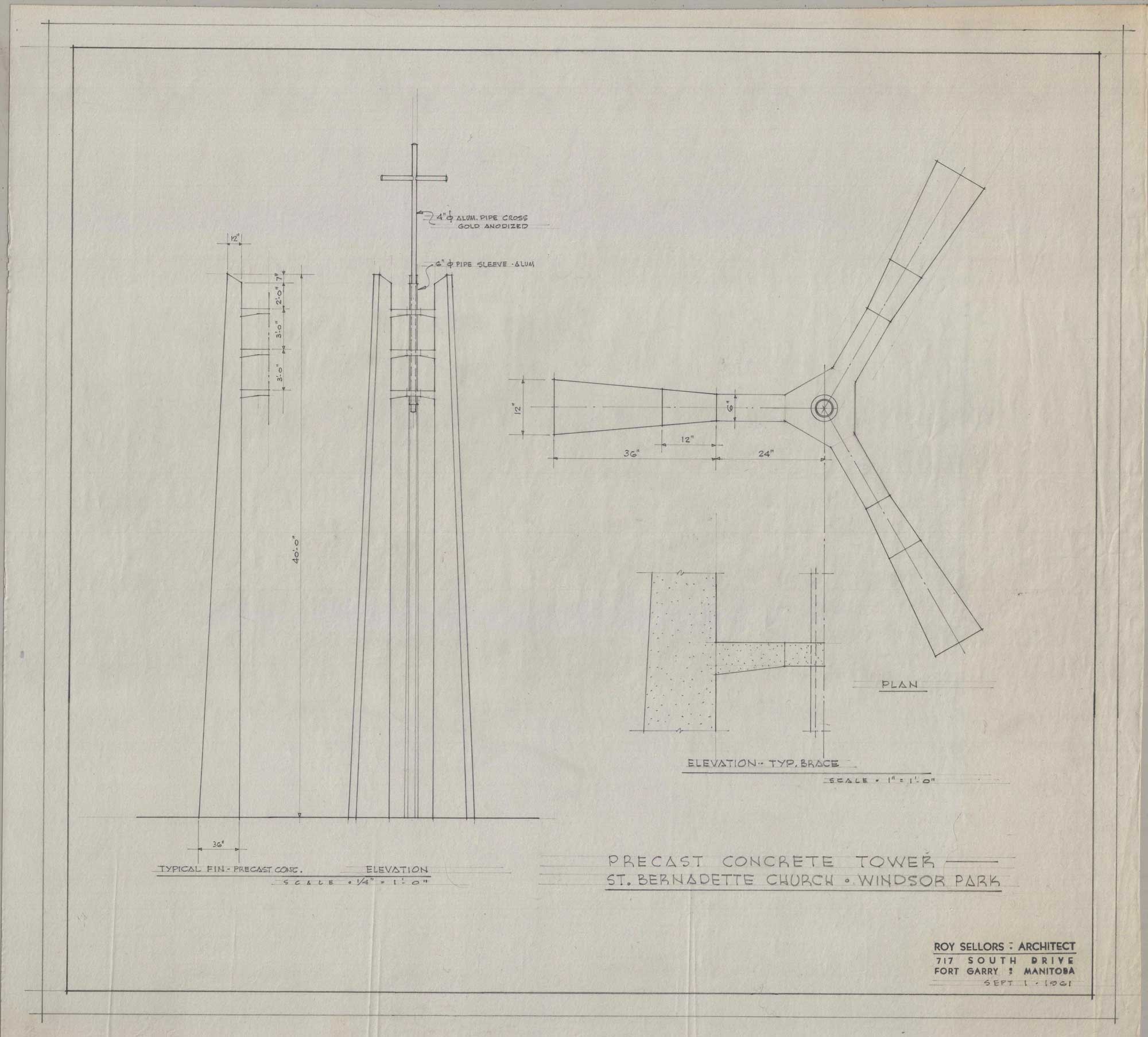

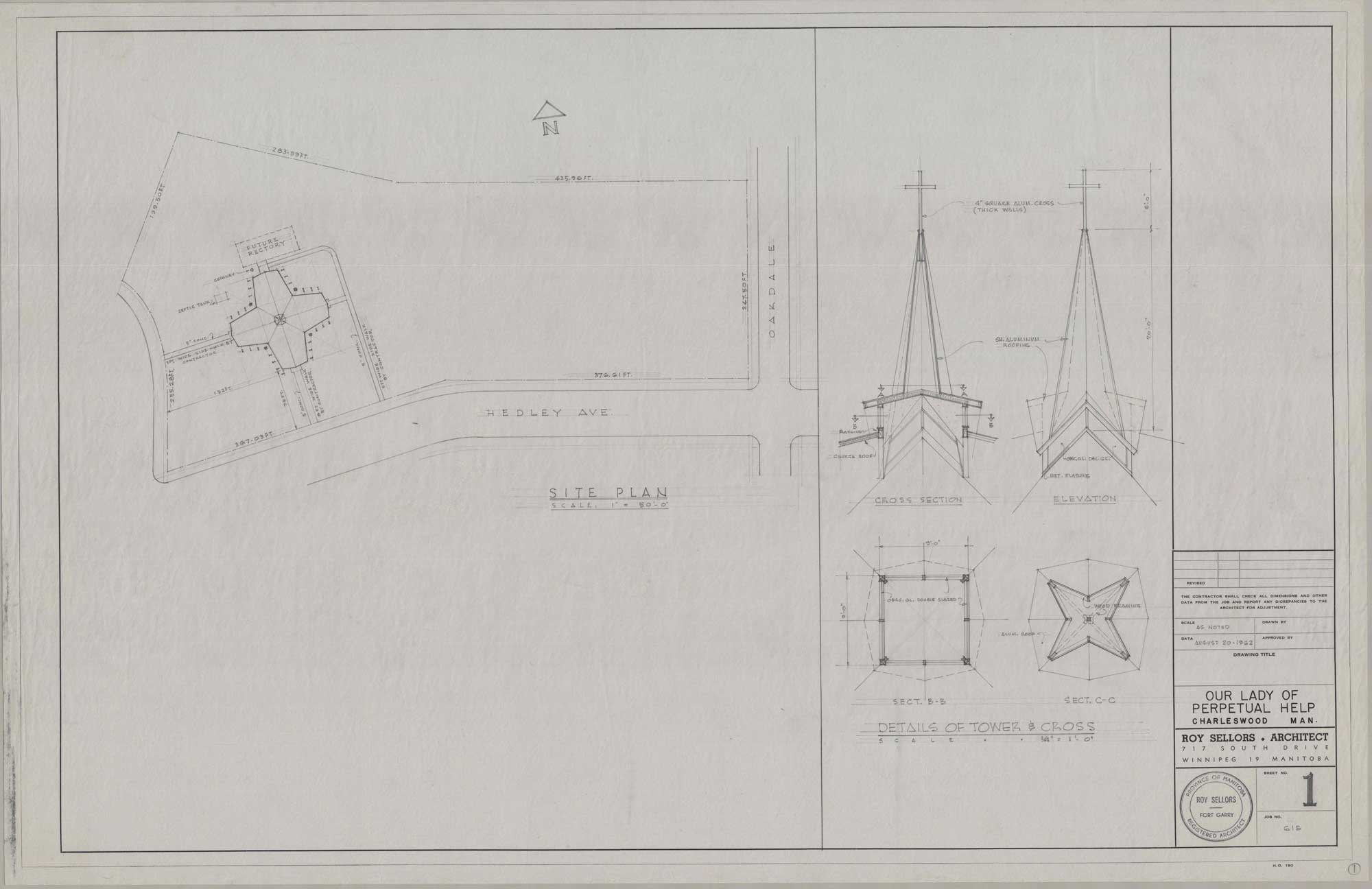

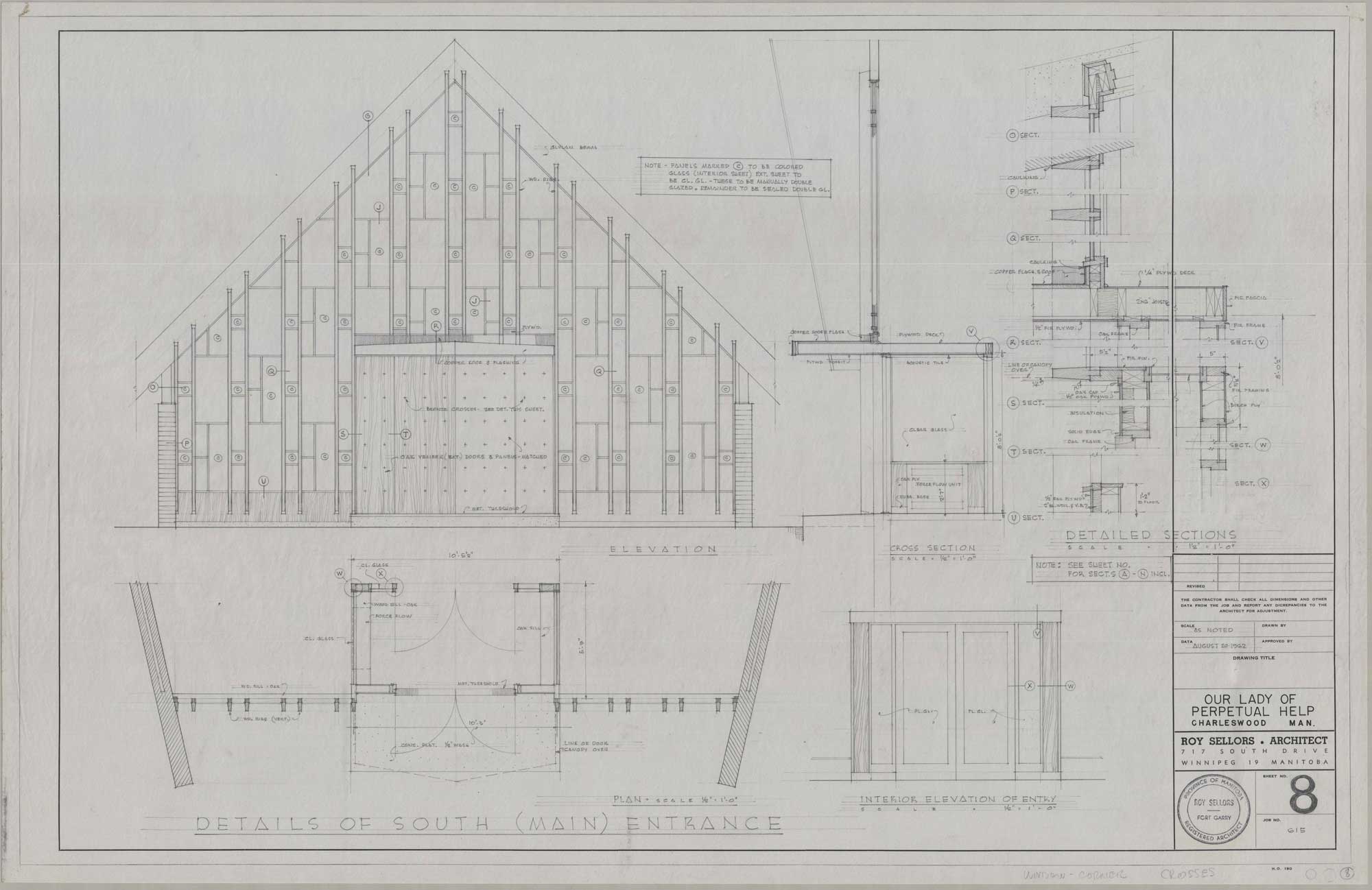

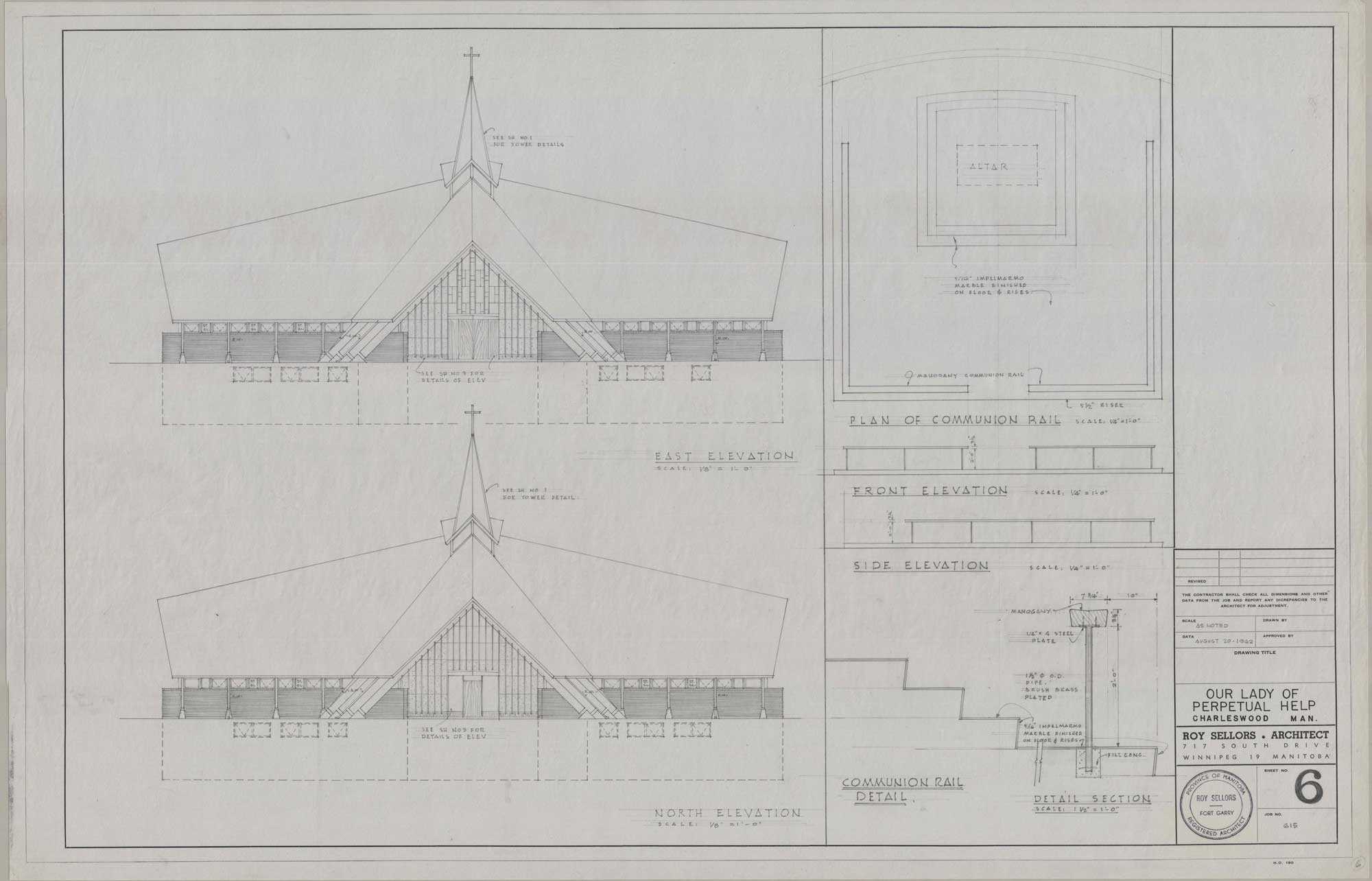

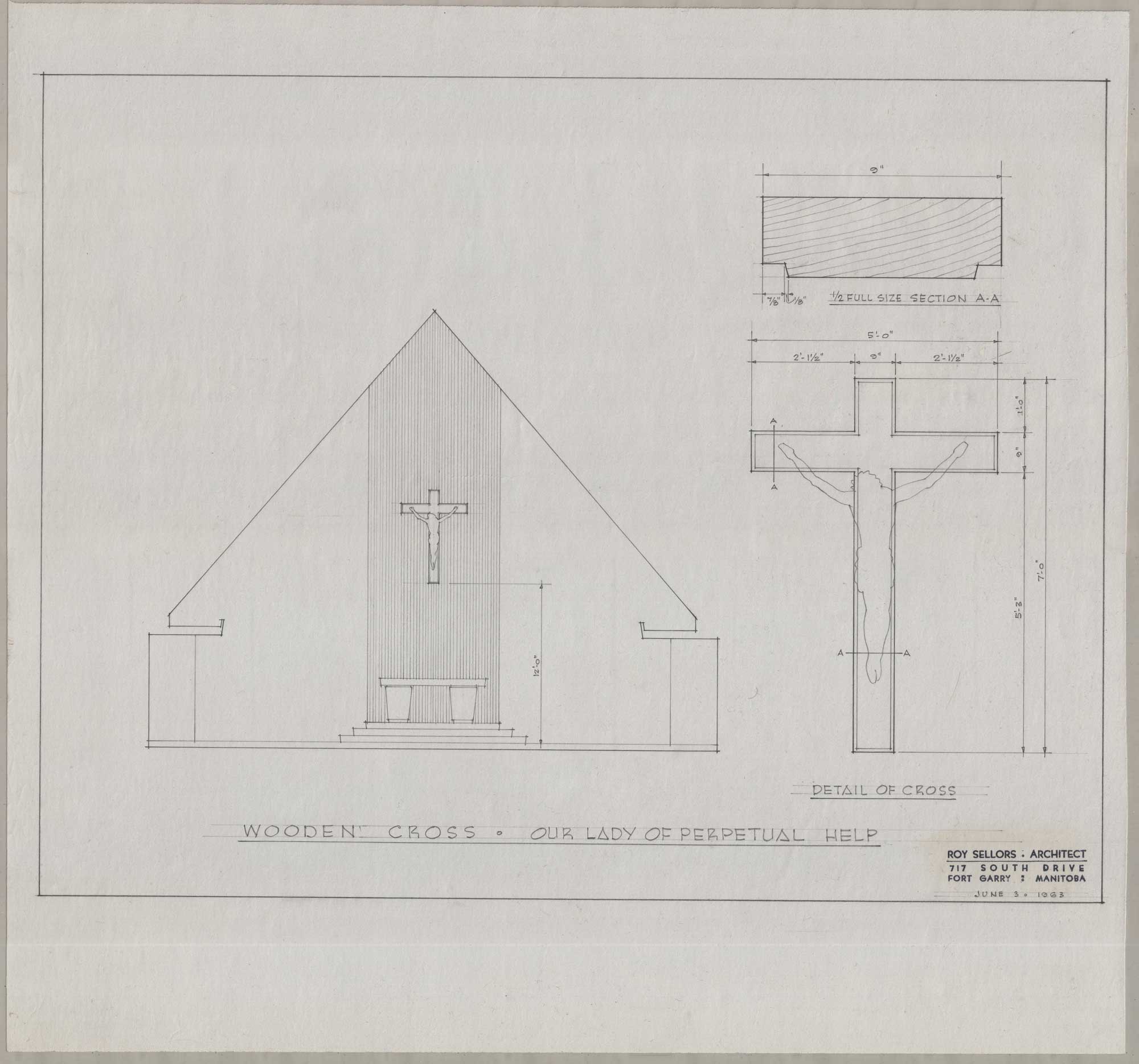

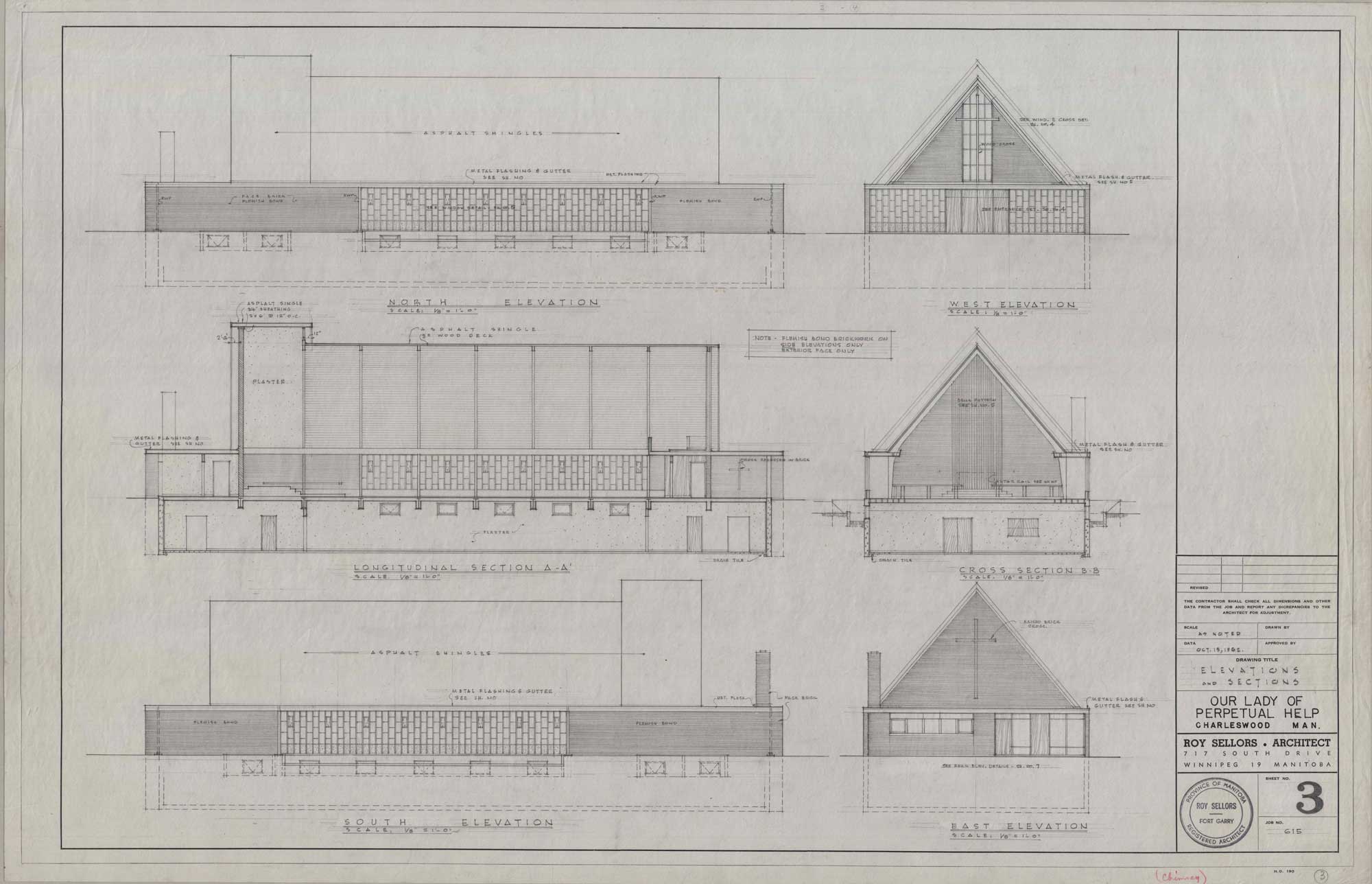

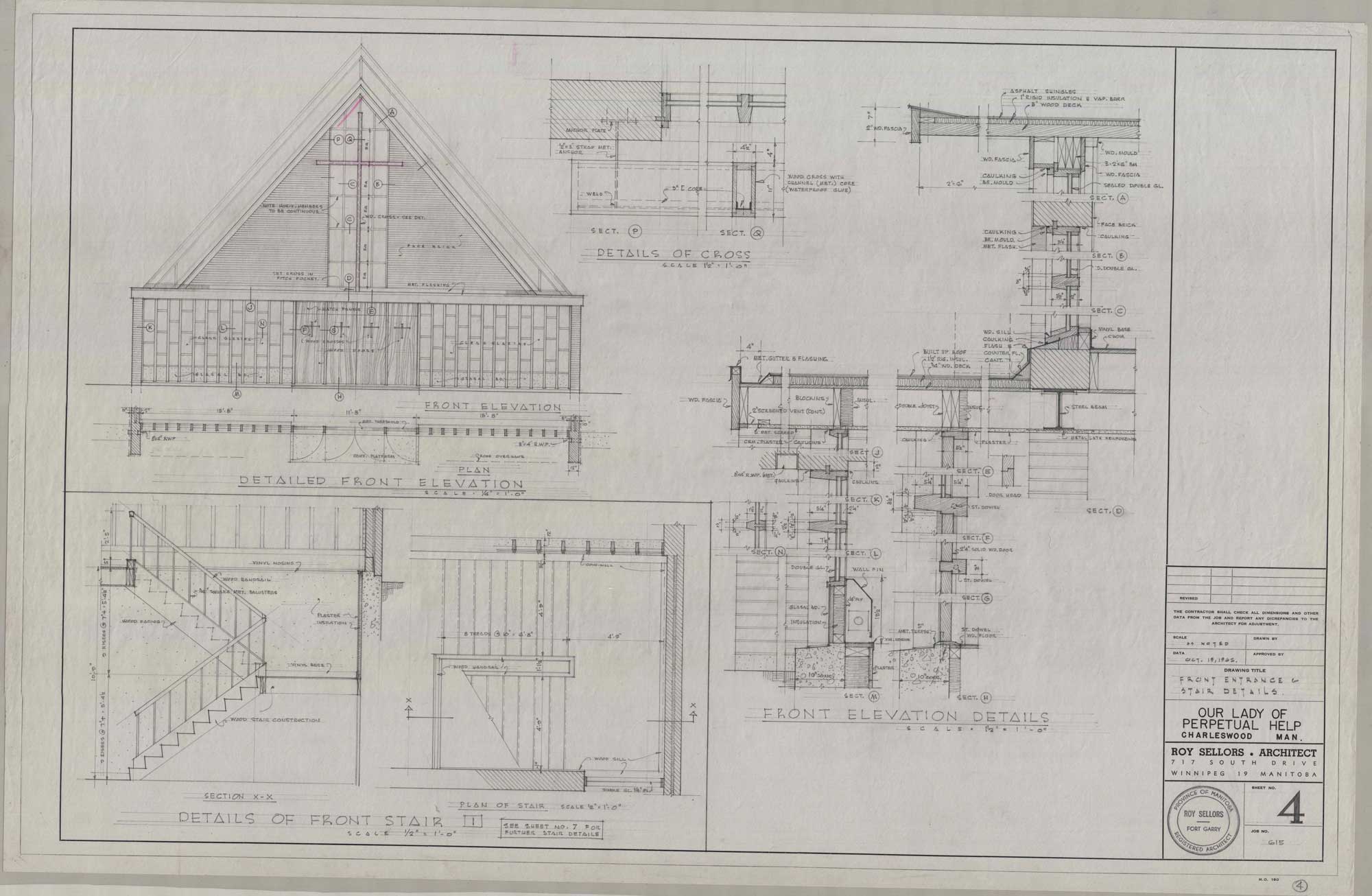

Sellors designed fourteen churches throughout the 1950s and 1960s. At times, his churches have steep and triangular frames that assert their monumentality as they appear to soar from the ground. In other instances, his churches sweep low across the lot, working harmoniously with the flatness of the prairie landscape. Though the buildings' designs varied and were informed by the interests of their respective parishes, Sellors’s consolidated approach to religious architecture is expressed through precise forms and thoughtful provisions for light. His use of form and light addressed the common interests of modern architecture and the liturgical movement in functionality and simplicity as a pathway to contemporary connection.

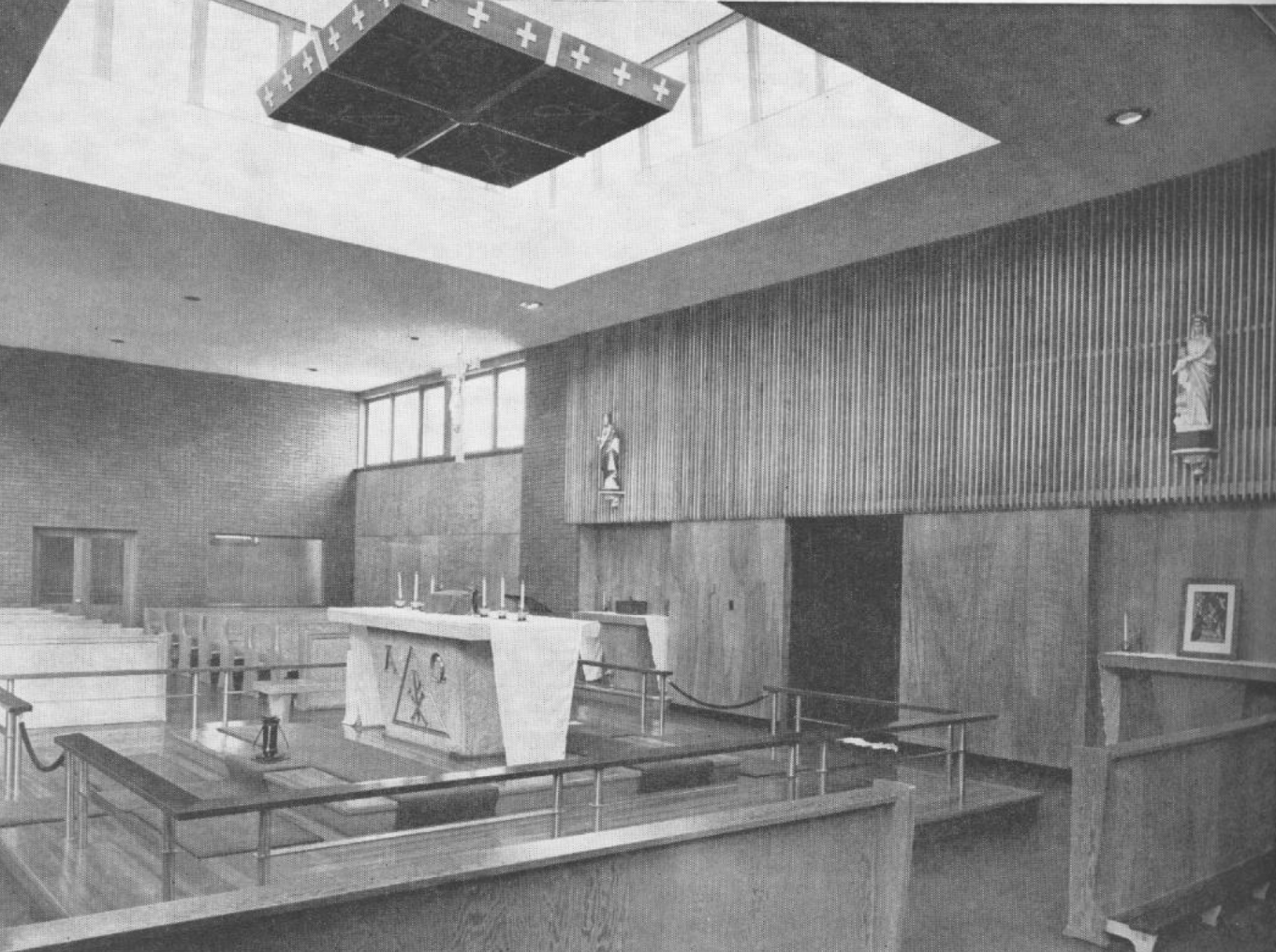

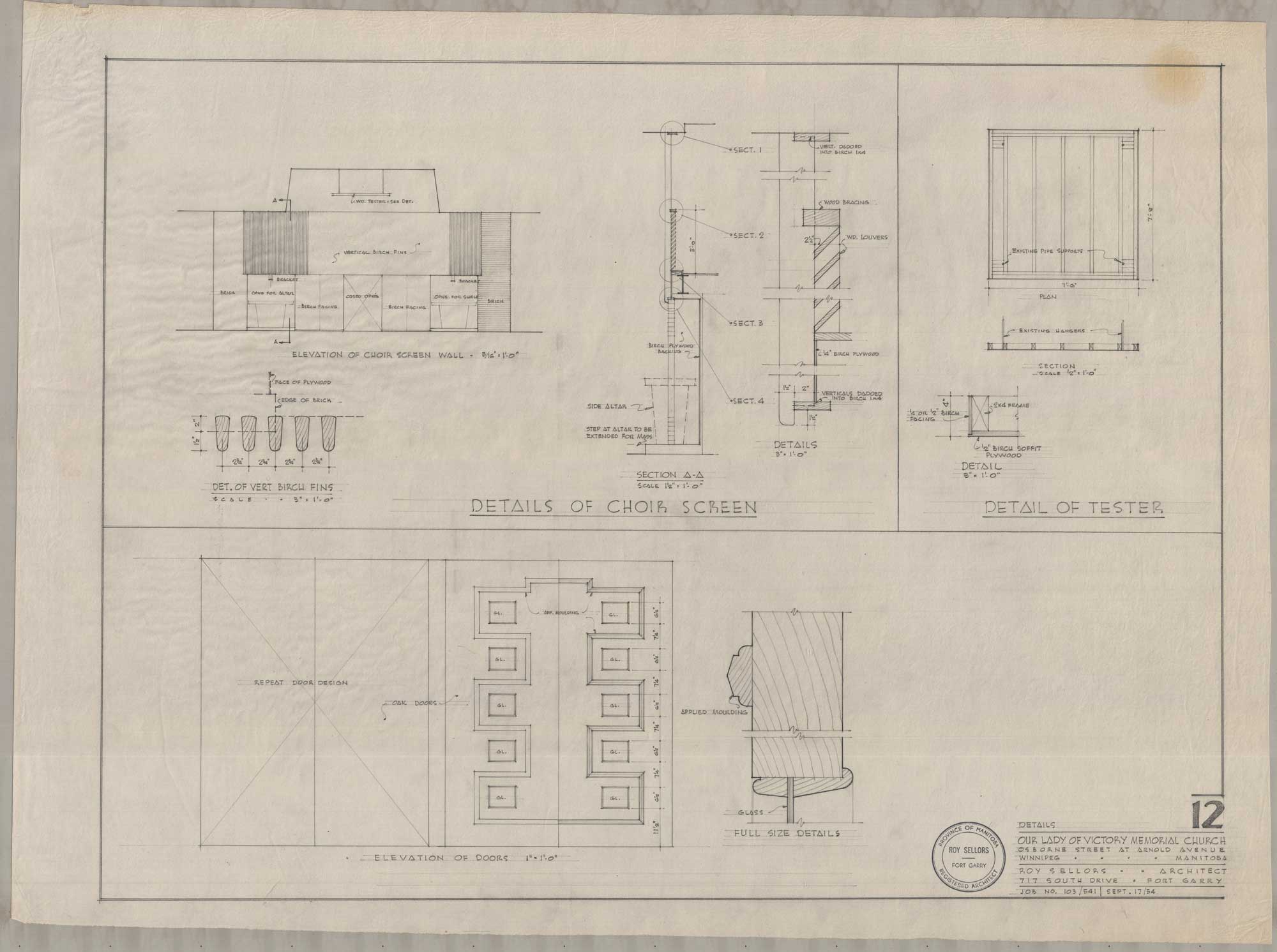

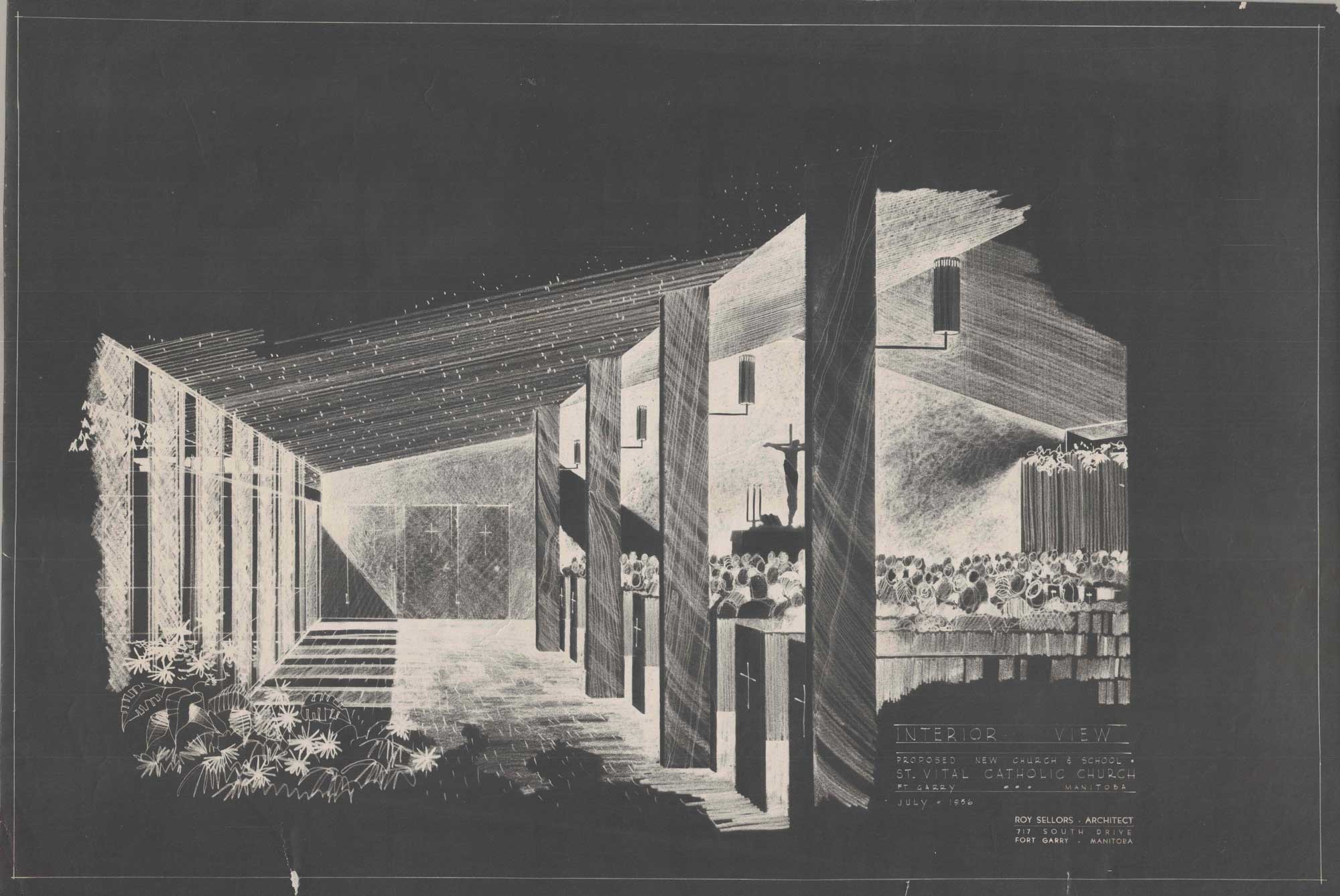

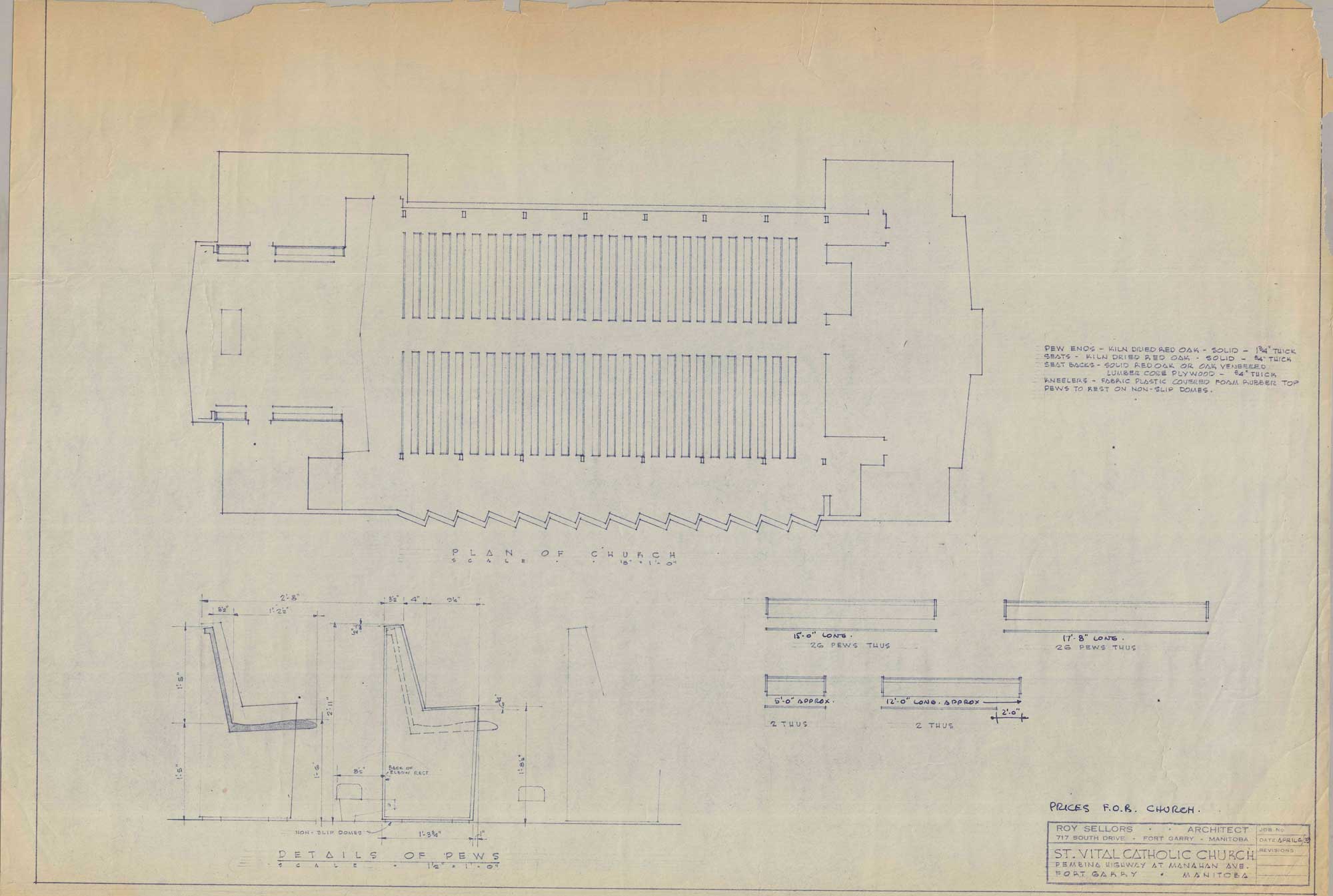

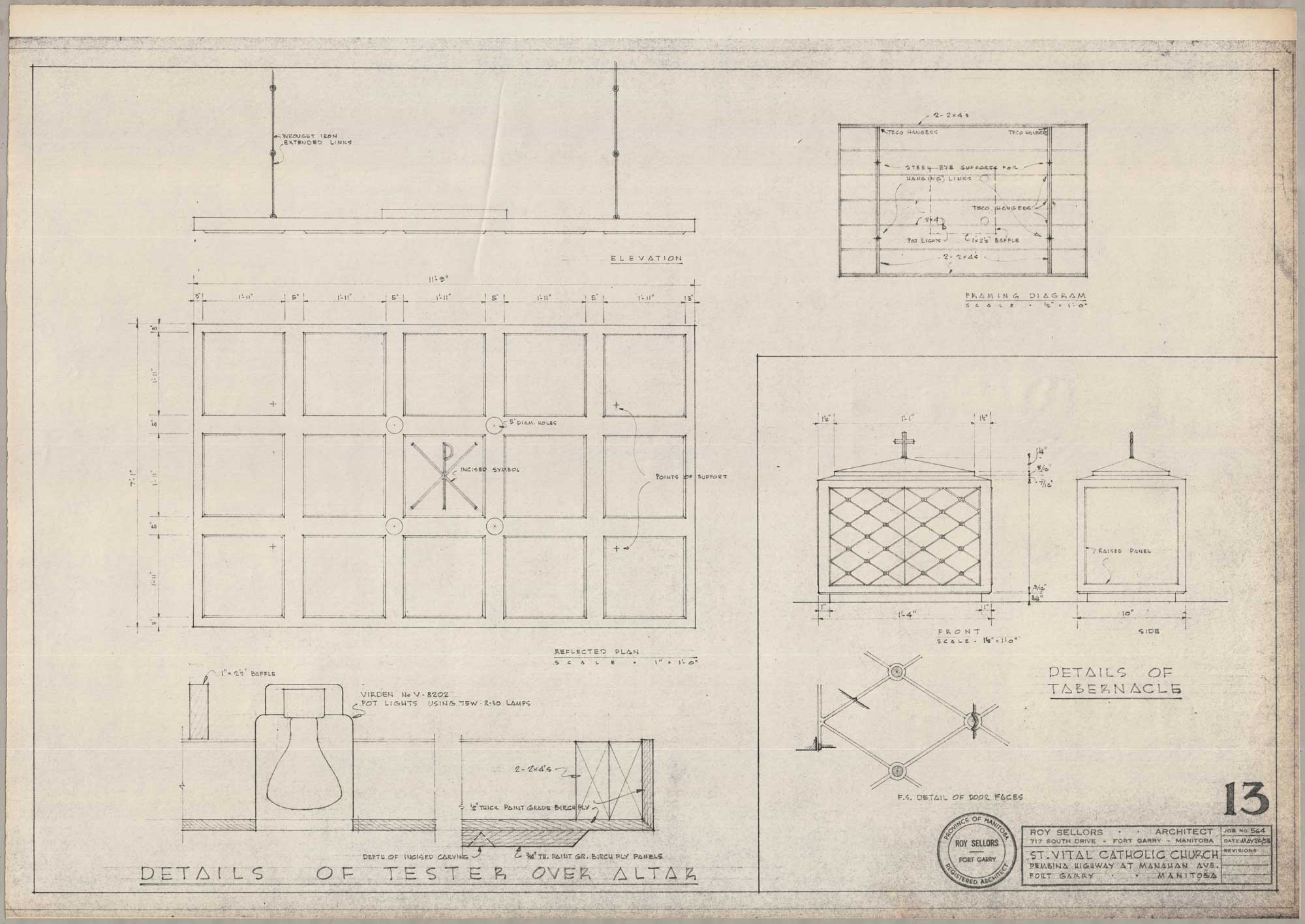

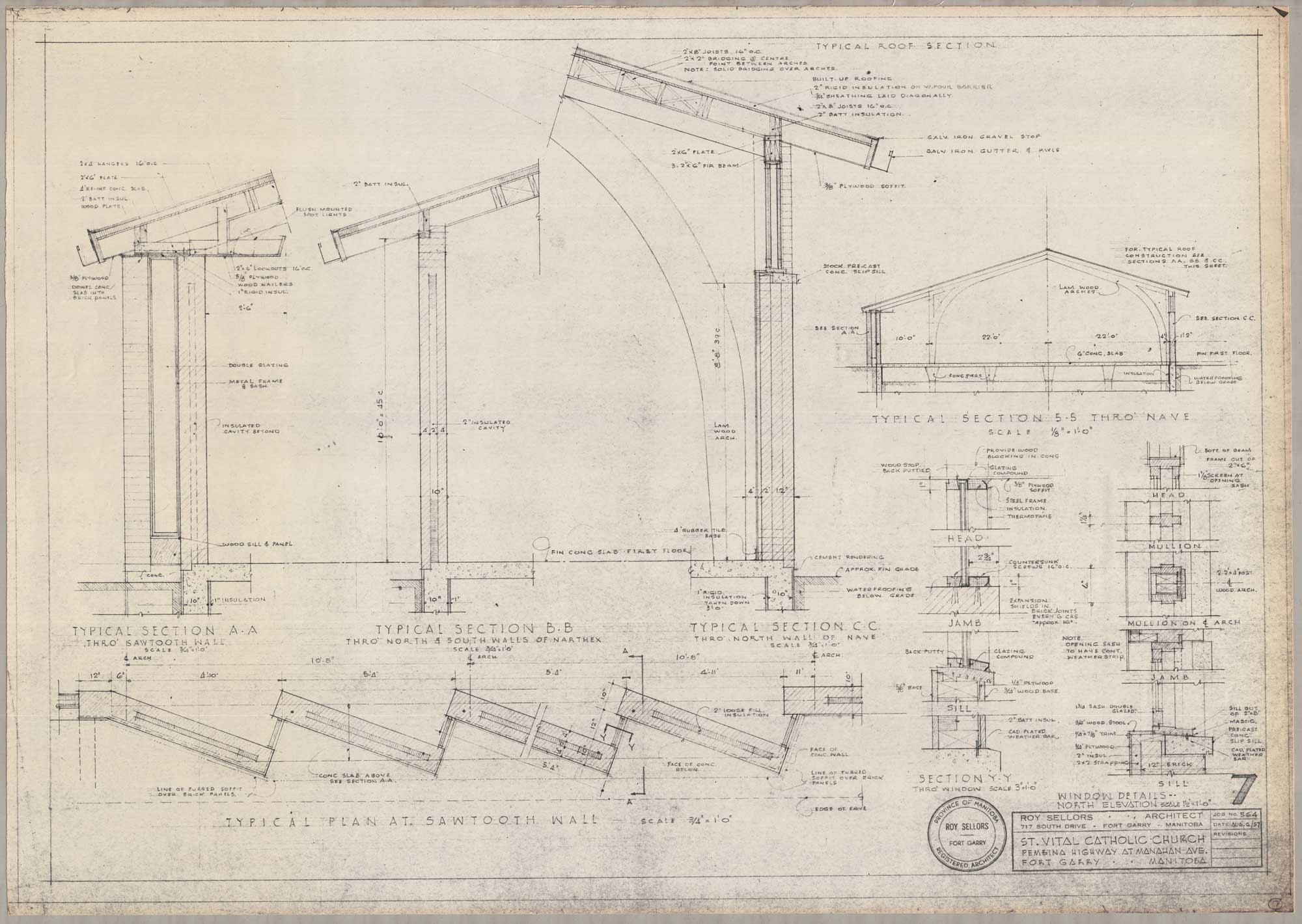

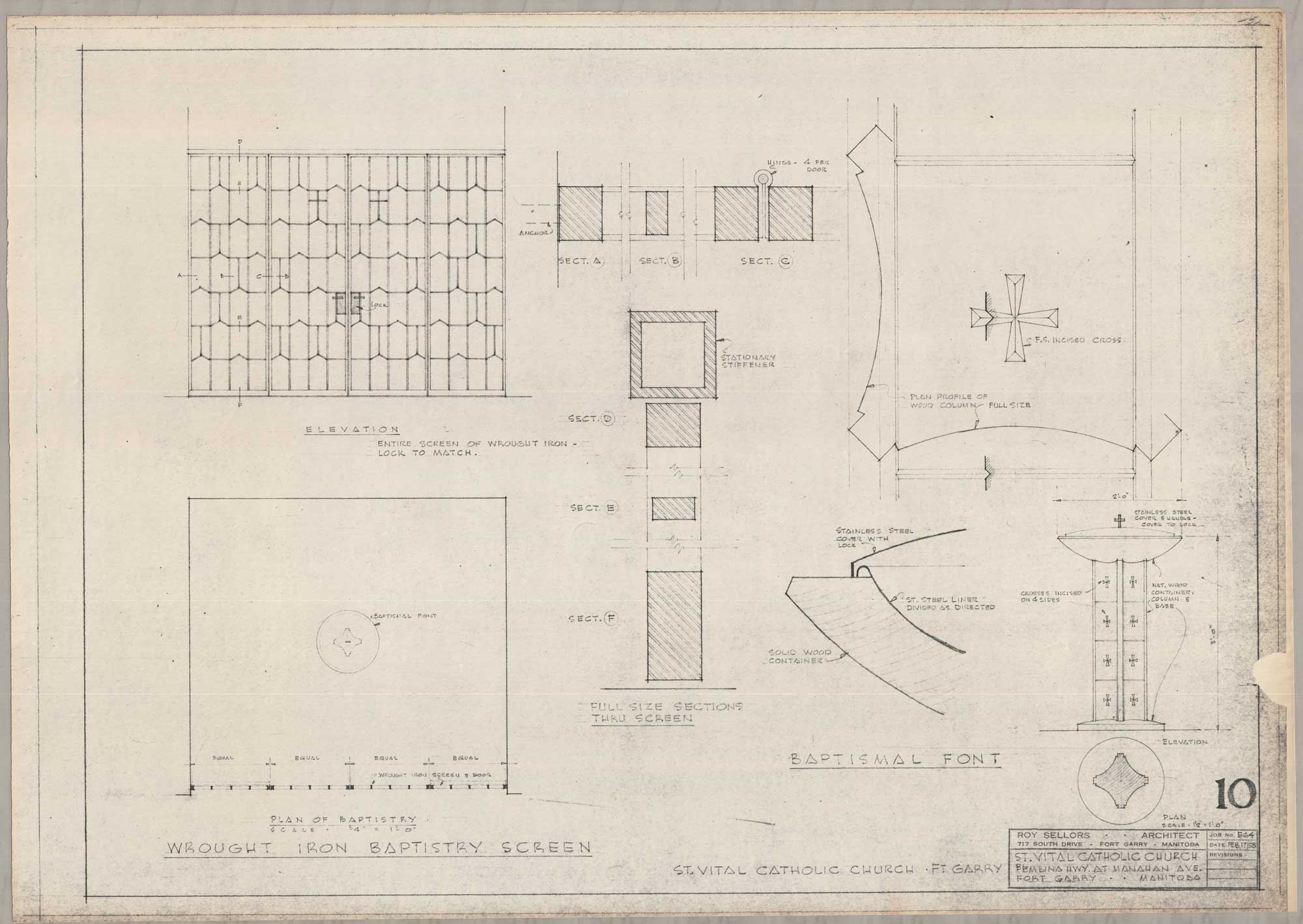

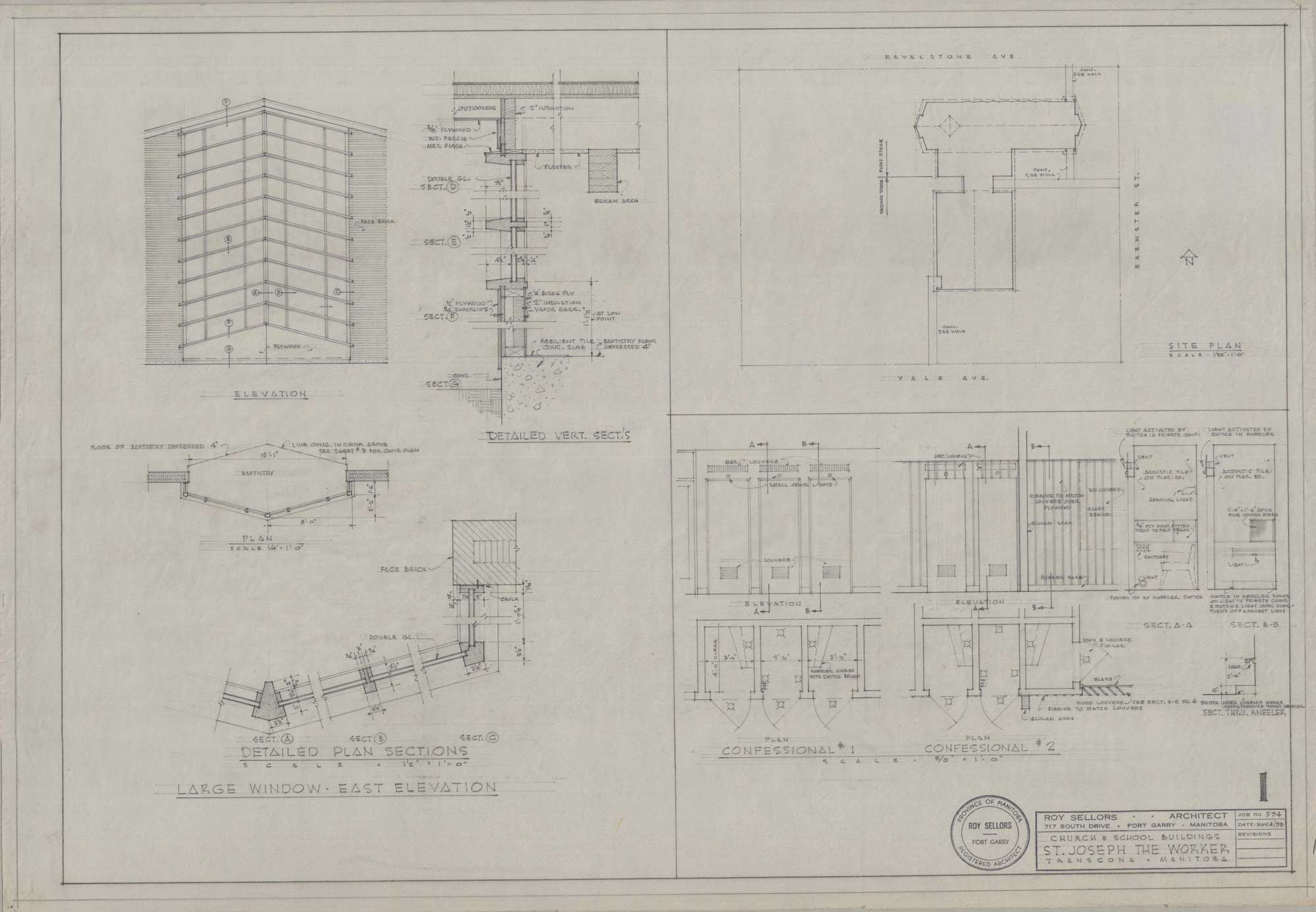

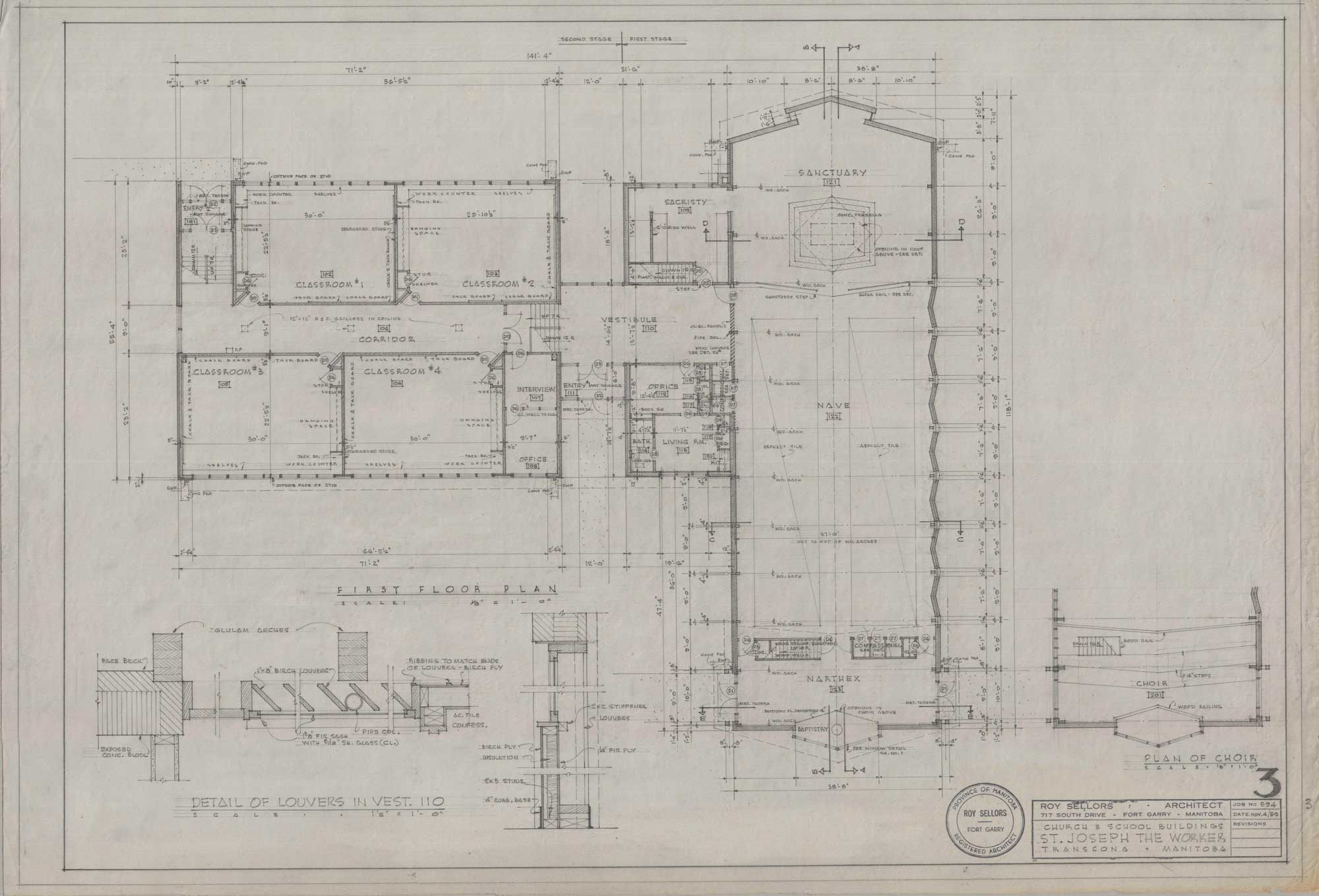

The clarity of Sellors’s churches is assured by their streamlined rooflines and minimalist ornamentation. He maintains the same degree of order in the interiors. In lieu of ornate decorations, Sellors constructed gleaming wooden arches that spanned from the narthex to the sanctuary and kept the walls bare. The clean and dynamic lines are further accentuated by the honest representation of construction materials, which mainly comprise of concrete, brick, and finished wood.

Laminated wooden arches are a fixture in Sellors’ designs. His constant use of laminated wood can be traced to the development of new lamination methods. The approach to lamination became more advanced during the Second World War. Such advancements were driven by the need to build lightweight airplane parts that were stronger and could be easily manipulated. In the postwar period, the new lamination methods were used in modern church construction. Architects were attracted to laminated wood’s pliability and price tag. Beyond the practical appeal of the material, laminated wood brought tremendous visual warmth to the space.

Sellors further elevates his religious designs when he experiments with different pathways for light. Some of his churches are illuminated with glass walls fixed at the entrances. Others are flooded with light streaming from clerestory windows that wrap around the structure. The careful placement of windows affirms the churches’ dramatic forms and alleviates the intensity of building materials. The windows also compel visitors to shift their attention towards the sanctuary and upwards to the heavens.

Sellors's church designs are firmly grounded in the traditions of modernist architecture of the postwar period. At the same time, his designs reflect the liturgical movement and the changing attitudes towards worship.