Biography

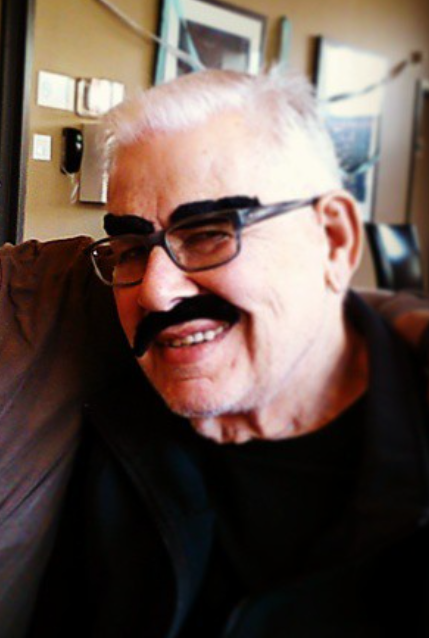

Julius Roy (Roy) Izen was born to Sarah (née Batkis) and Abraham David Izen on July 10th, 1936. Roy grew up in the heart of Winnipeg’s North End, at 710 Selkirk, 407 Alfred, and 353 Magnus Avenues.1 As a child Roy lived with his parents and his aunt and uncle, Bertha and Harry Nemerovsky. He attended King Edward School.

By the time Roy was a teenager, his artistic ability and ambition were apparent. In the late 1940s Roy landed a job with Phillips-Gutkin Associates Ltd., one of Canada’s first animation studios, doing background character work and design.2

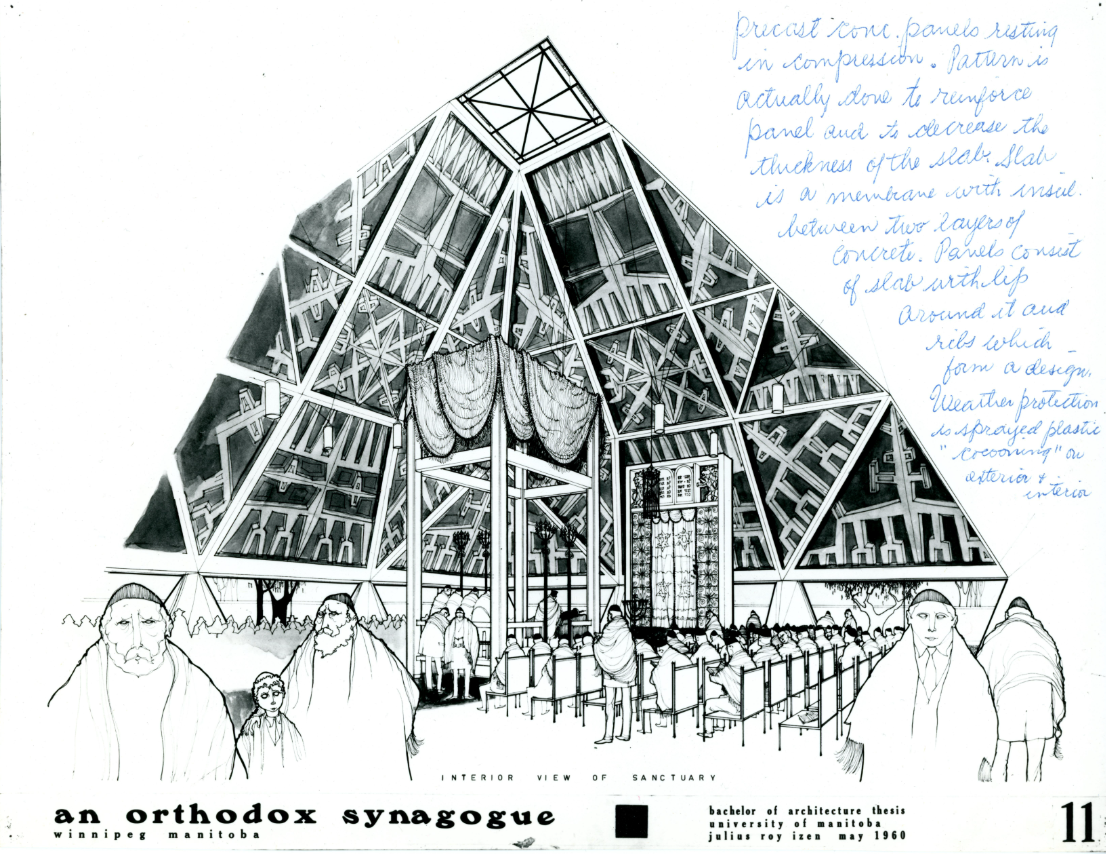

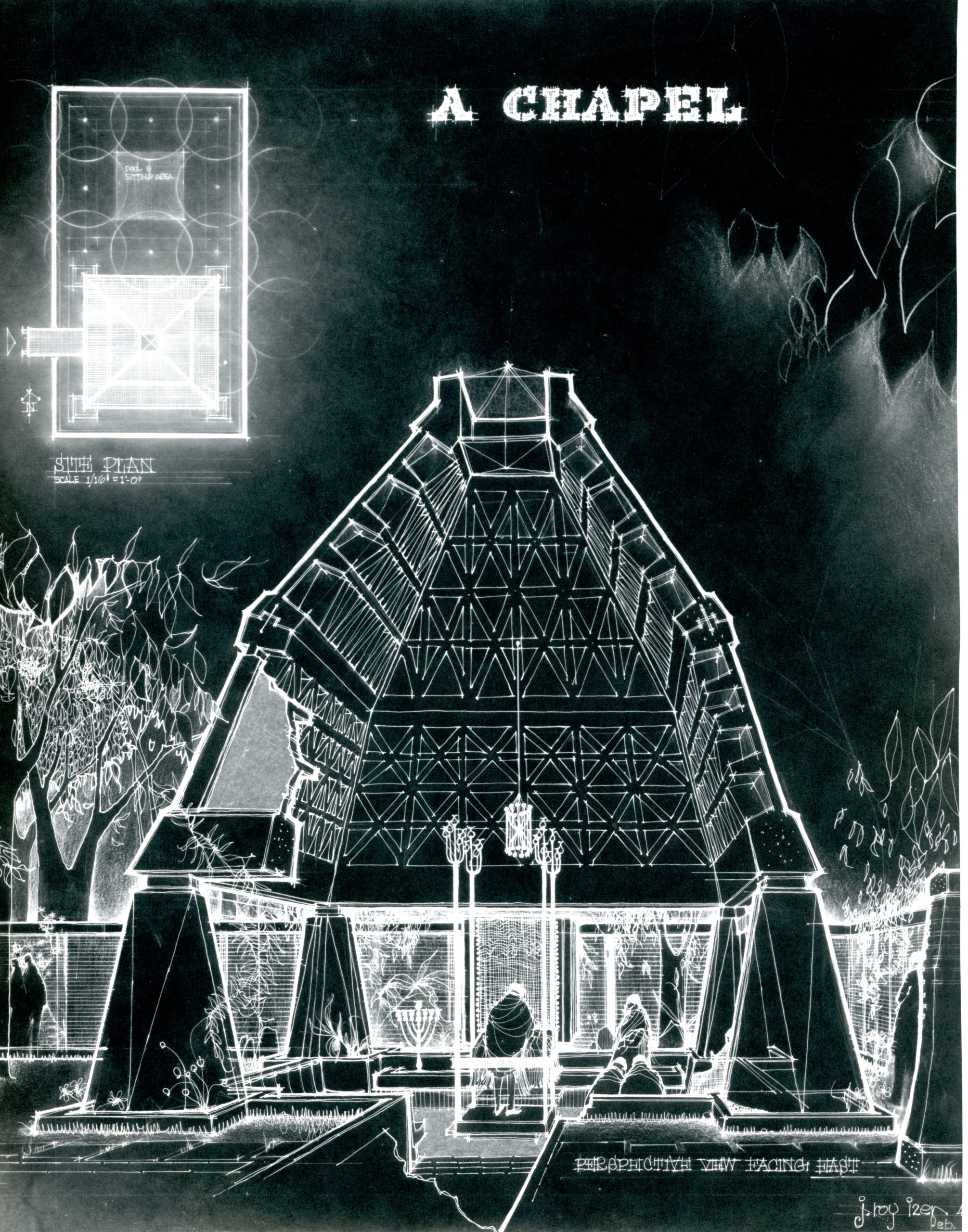

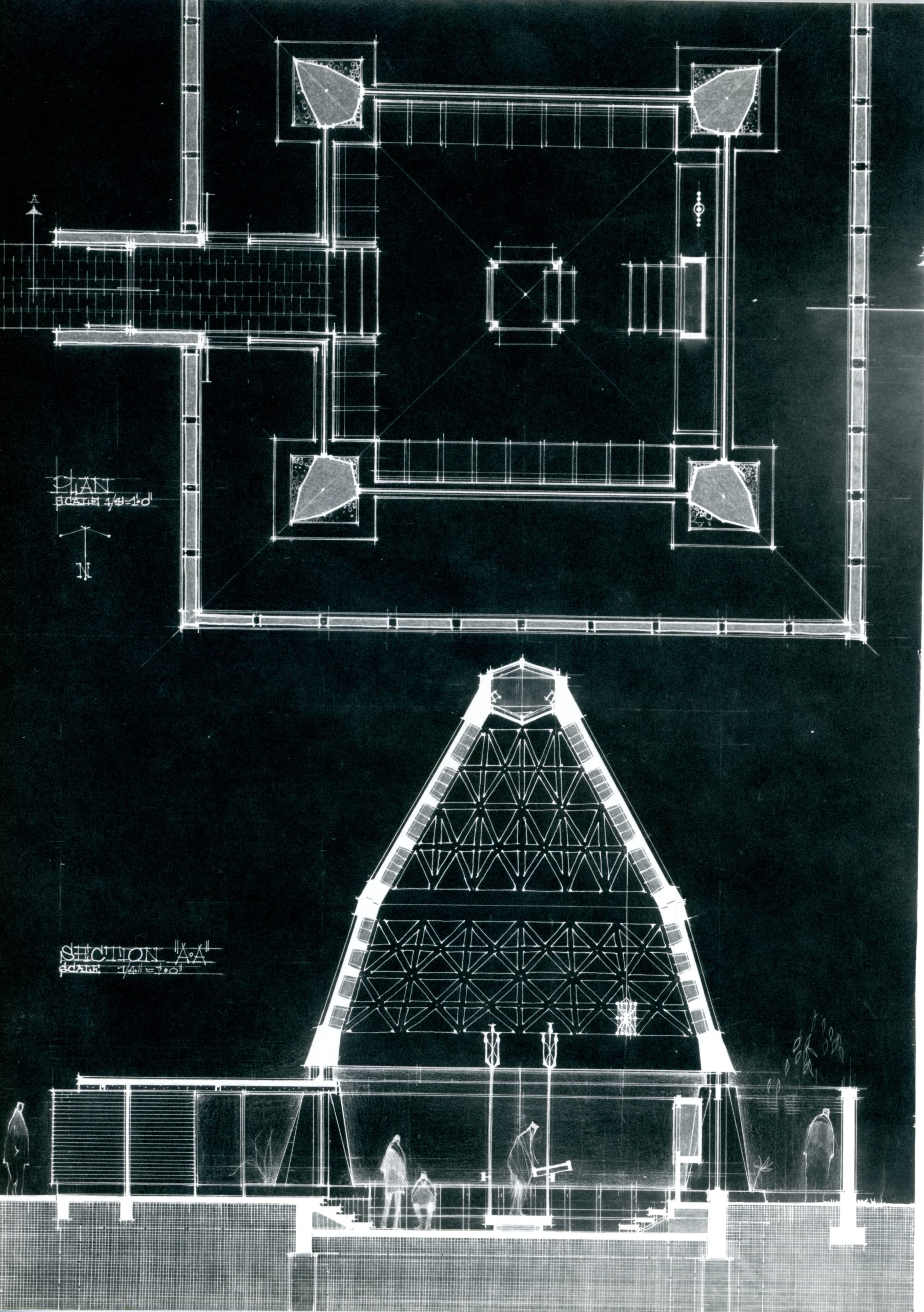

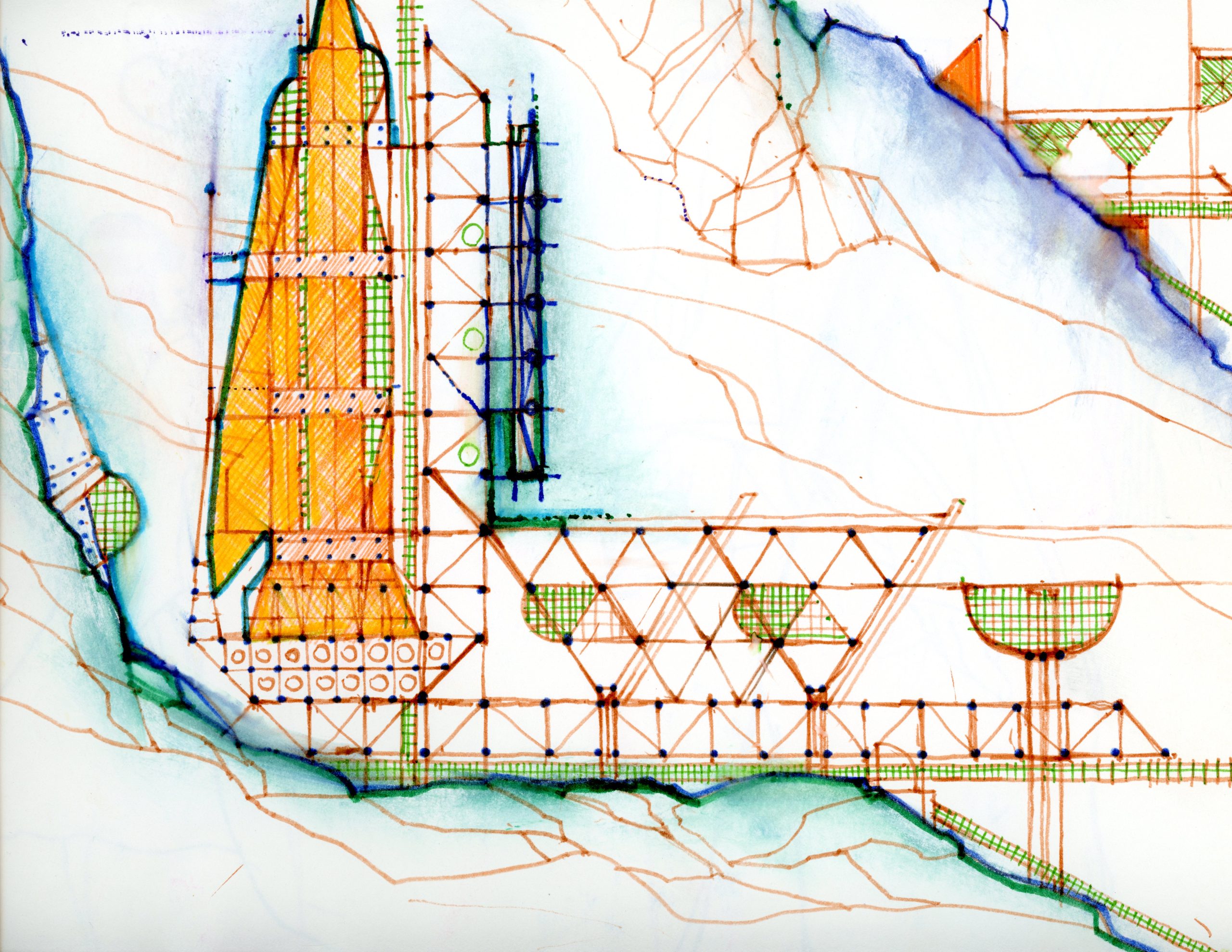

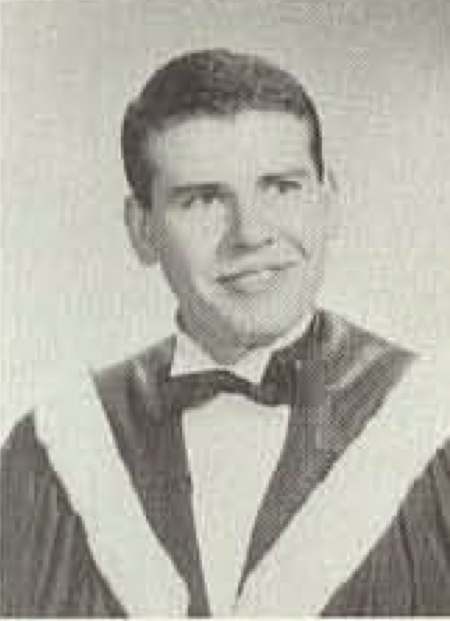

Roy worked hard to earn several scholarships to the University of Manitoba. He graduated with his bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1960, and according to the Brown and Gold (the University of Manitoba’s yearbook), Roy “won many design awards.3” The yearbook also notes Roy’s special interest in painting, and that he believed his future lay in South America.4

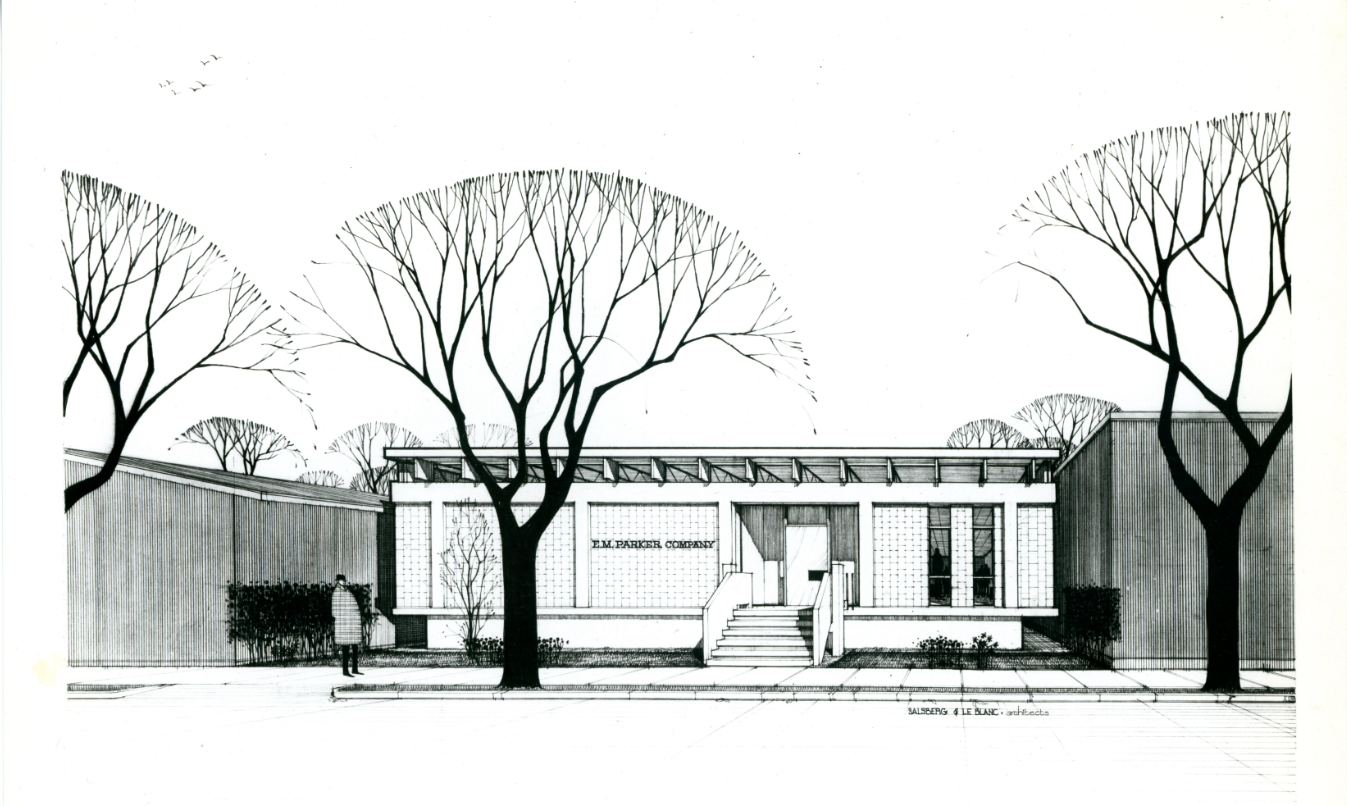

Roy’s future did not in fact lie in South America, however he did go South! Somewhat. In 1961 he was awarded a Canadian Council Scholarship to obtain his master’s degree in architecture at an American university. He selected the Massachusetts Institutes of Technology, and while living in Boston he was employed by the firm of Salzberg and LeBlanc. Roy returned to Winnipeg in 1963.

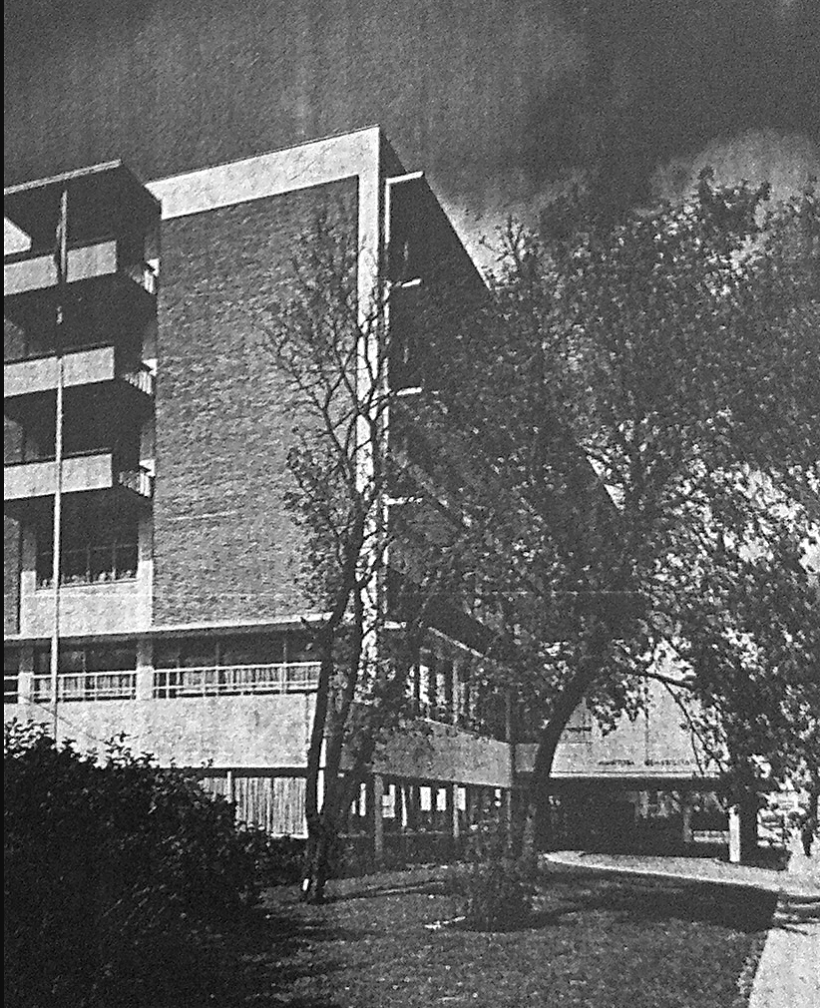

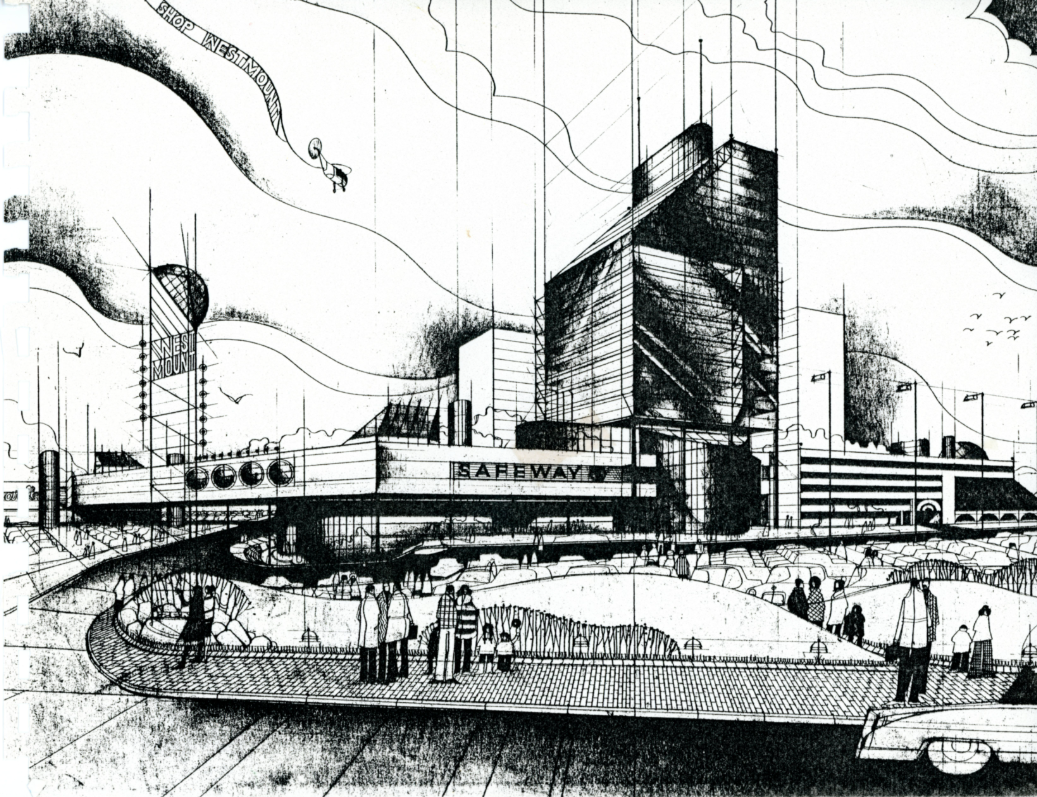

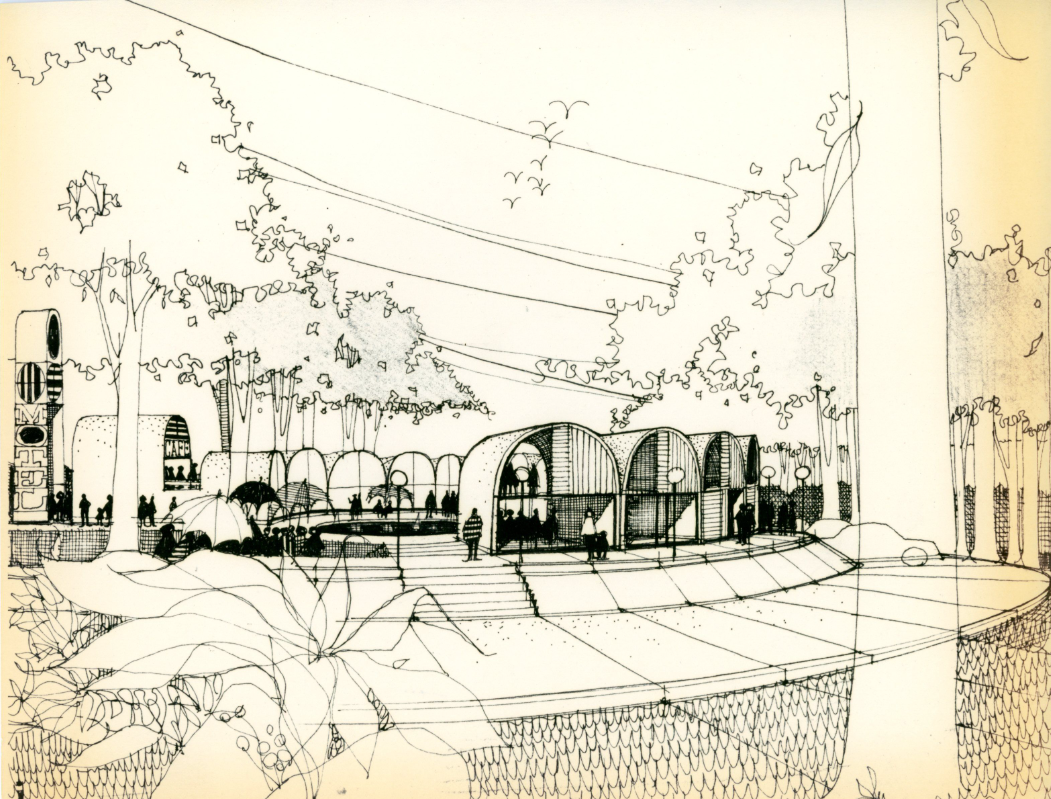

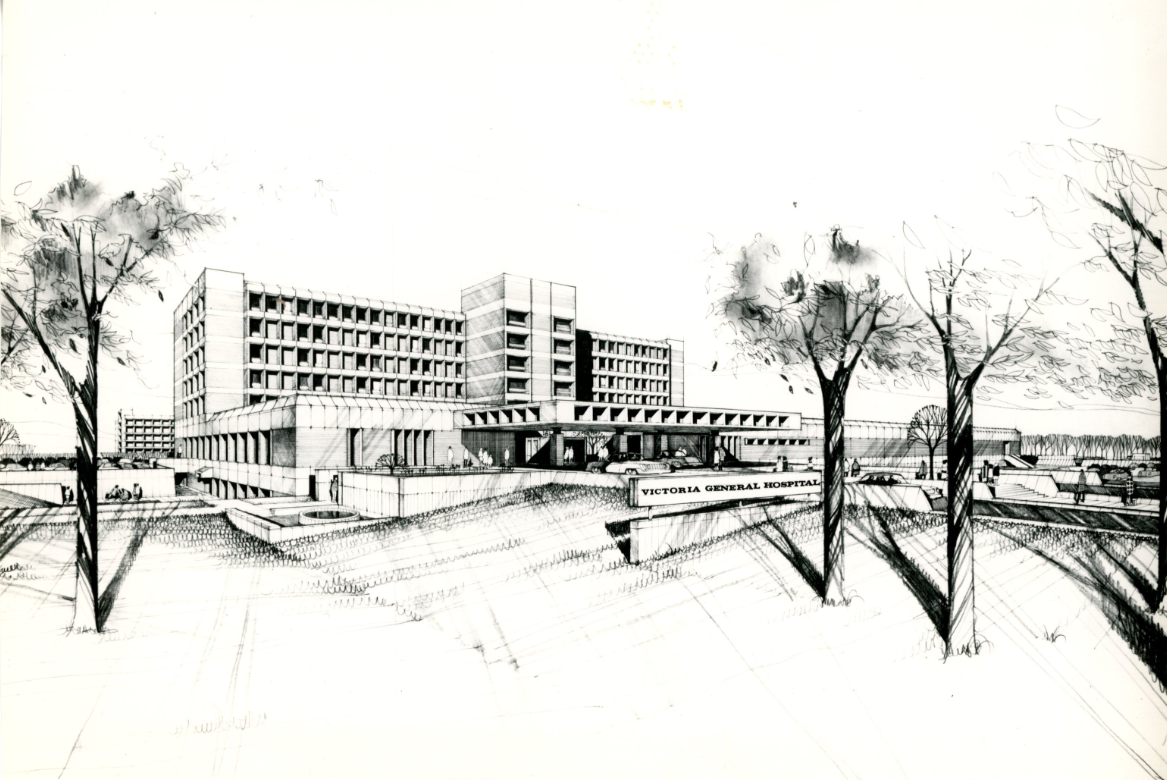

Roy’s initial roles as a designer/architect working in Winnipeg were held at Blankstein Coop Gillmore & Hanna Architects, the LM Architectural Group, and TEN Architectural Group, throughout the early 1960s.

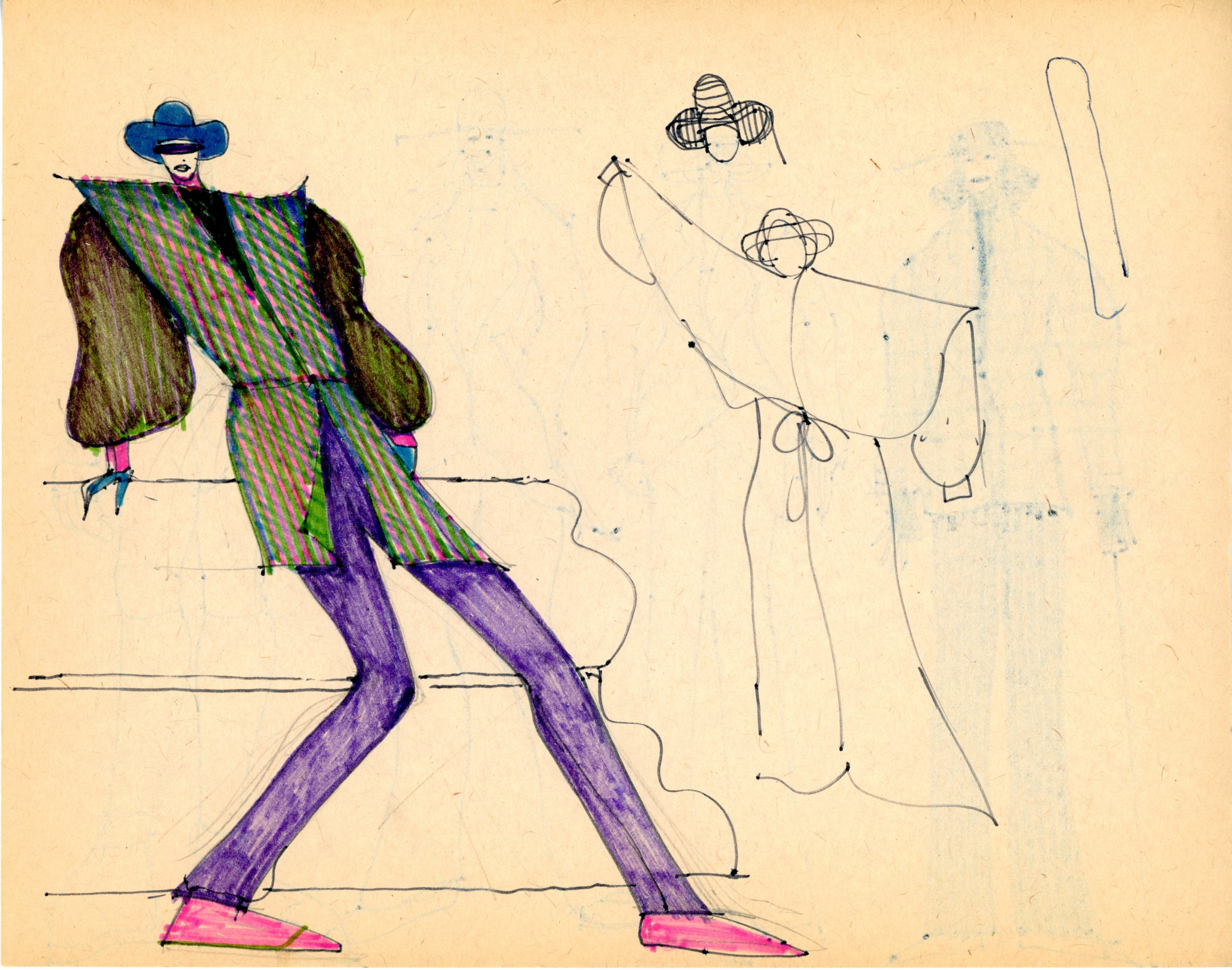

In addition to his work as an Architect, Roy also occasionally served as a set designer for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet. It was usual during the mid-twentieth century that architects would be hired to create sets for stage productions. At this time, the “Artistic Direction” of a ballet referred not its choreography or to the interpretation of the story, but rather to its costuming and set design.5 In 1963, Roy contributed sets to two ballets, Chiaroscuro and Mayerling.67 The Winnipeg Free press noted Roy’s collaboration with the costume designer as emphasizing the drama of Chiaroscuro through color contrast.8 To accomplish this, Roy and his partner Grant Marshal submitted 82 proposed designs!9

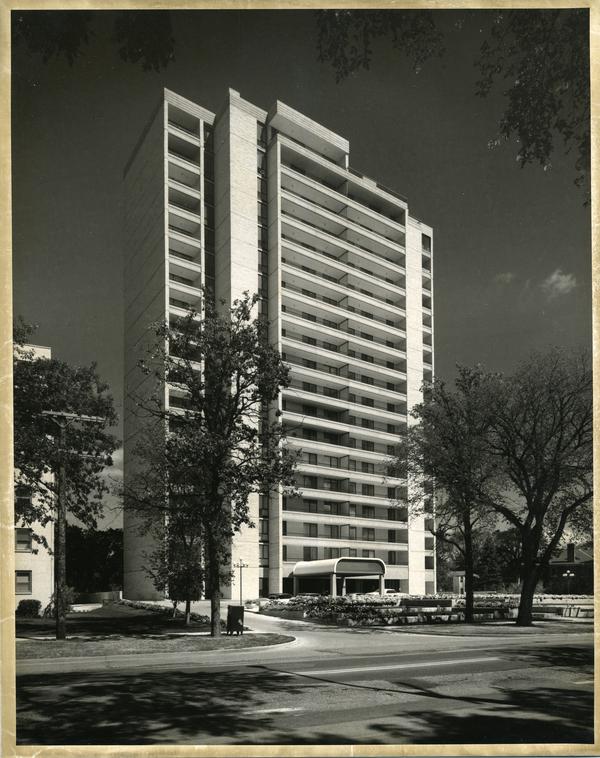

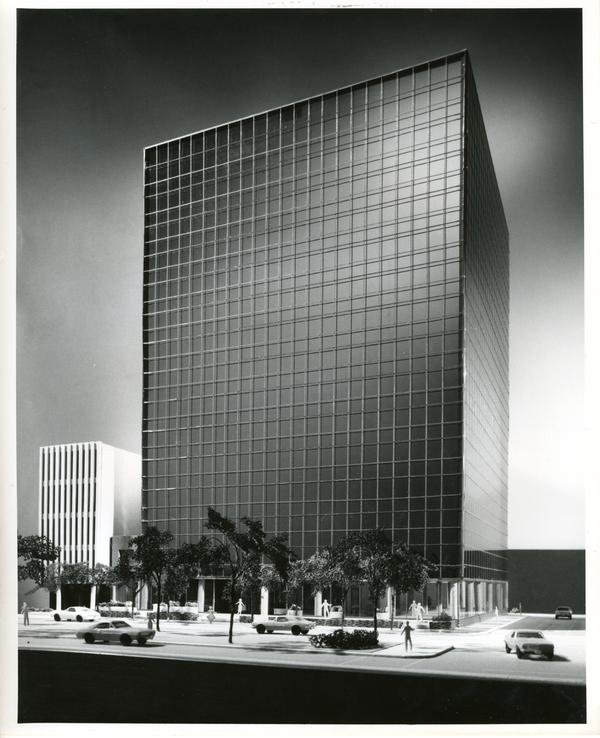

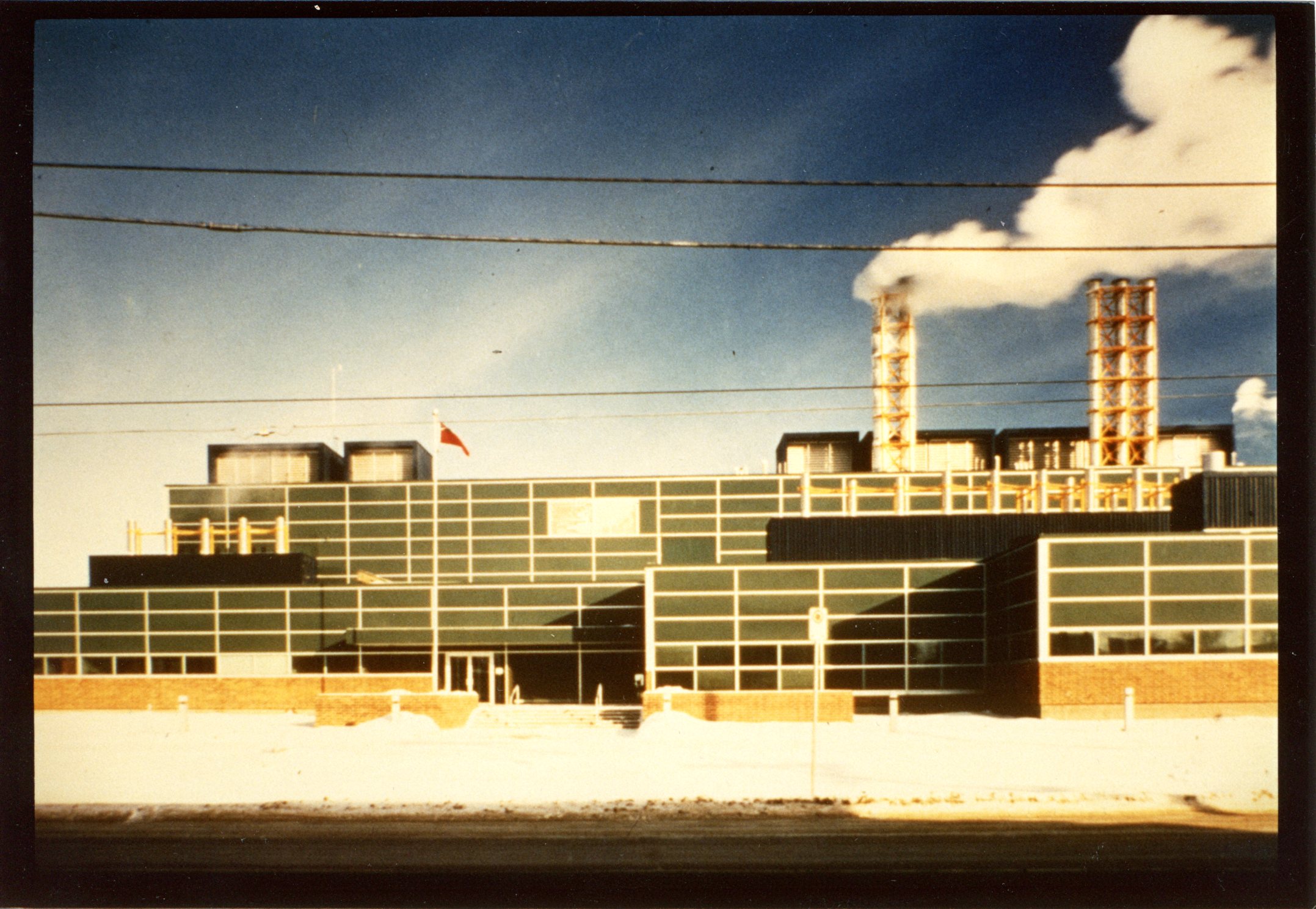

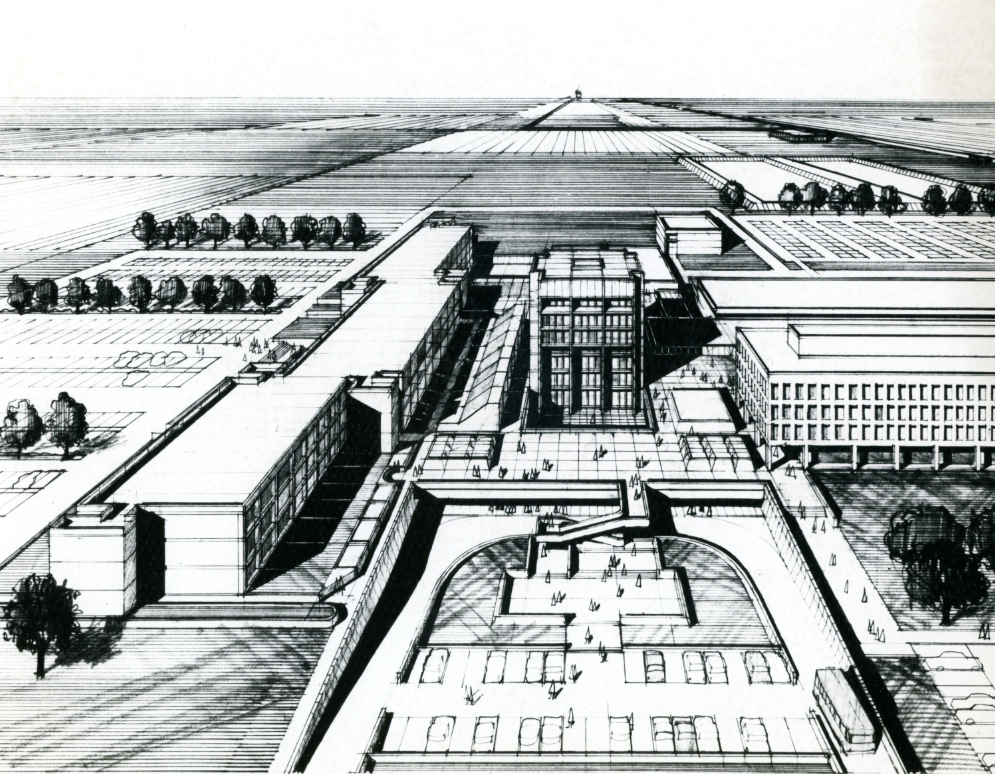

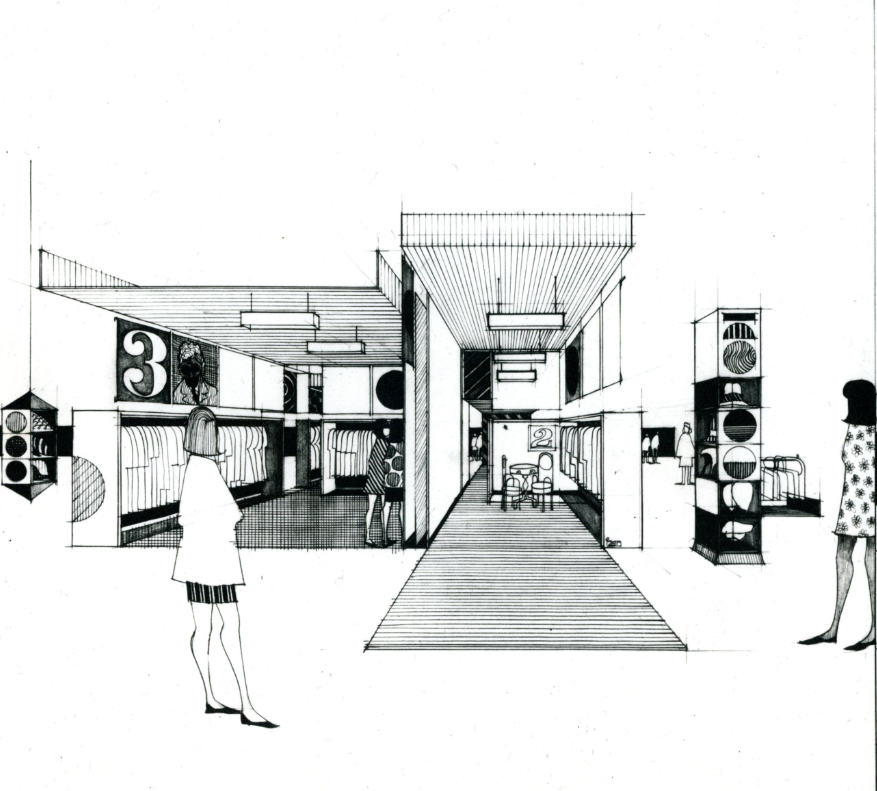

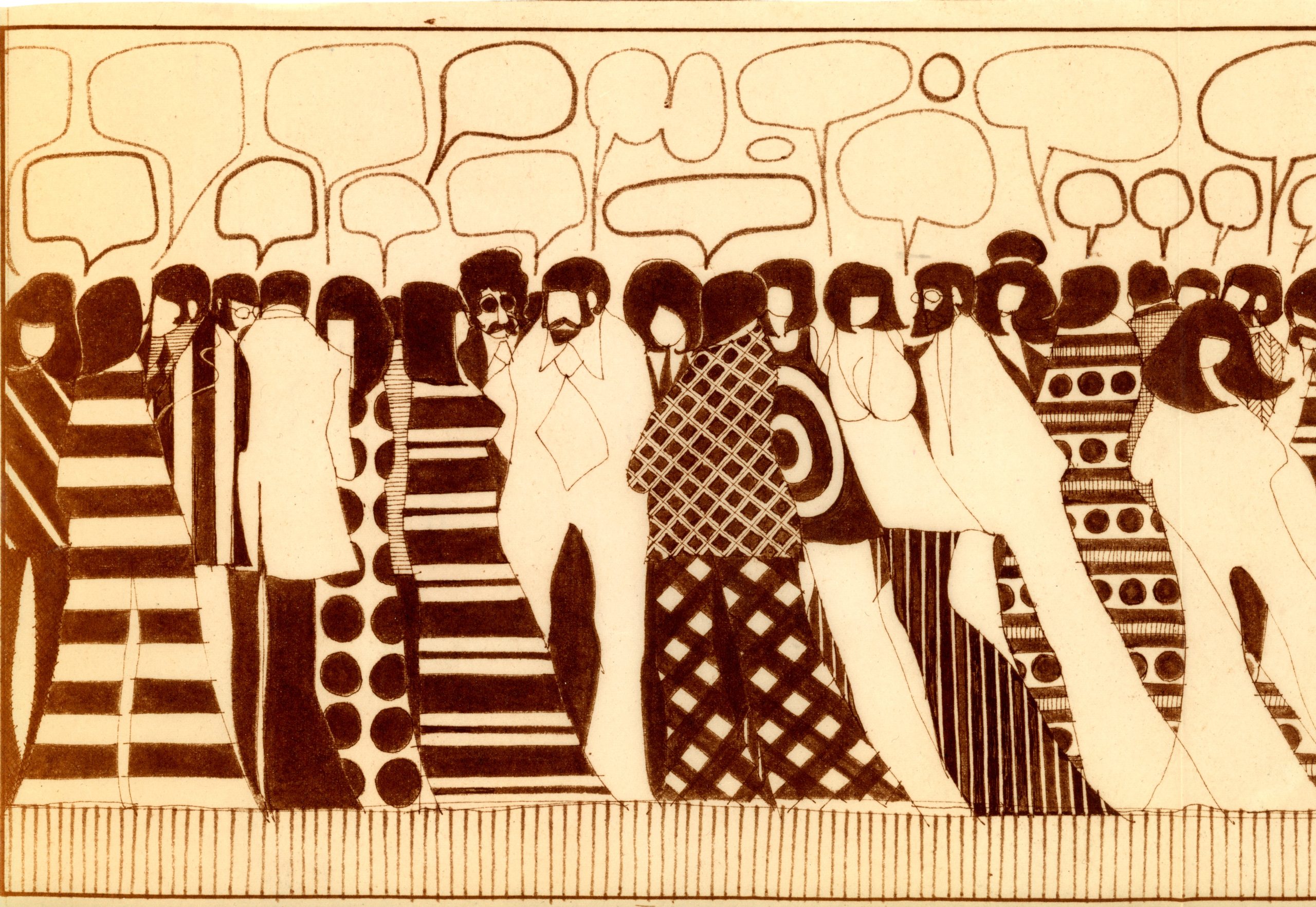

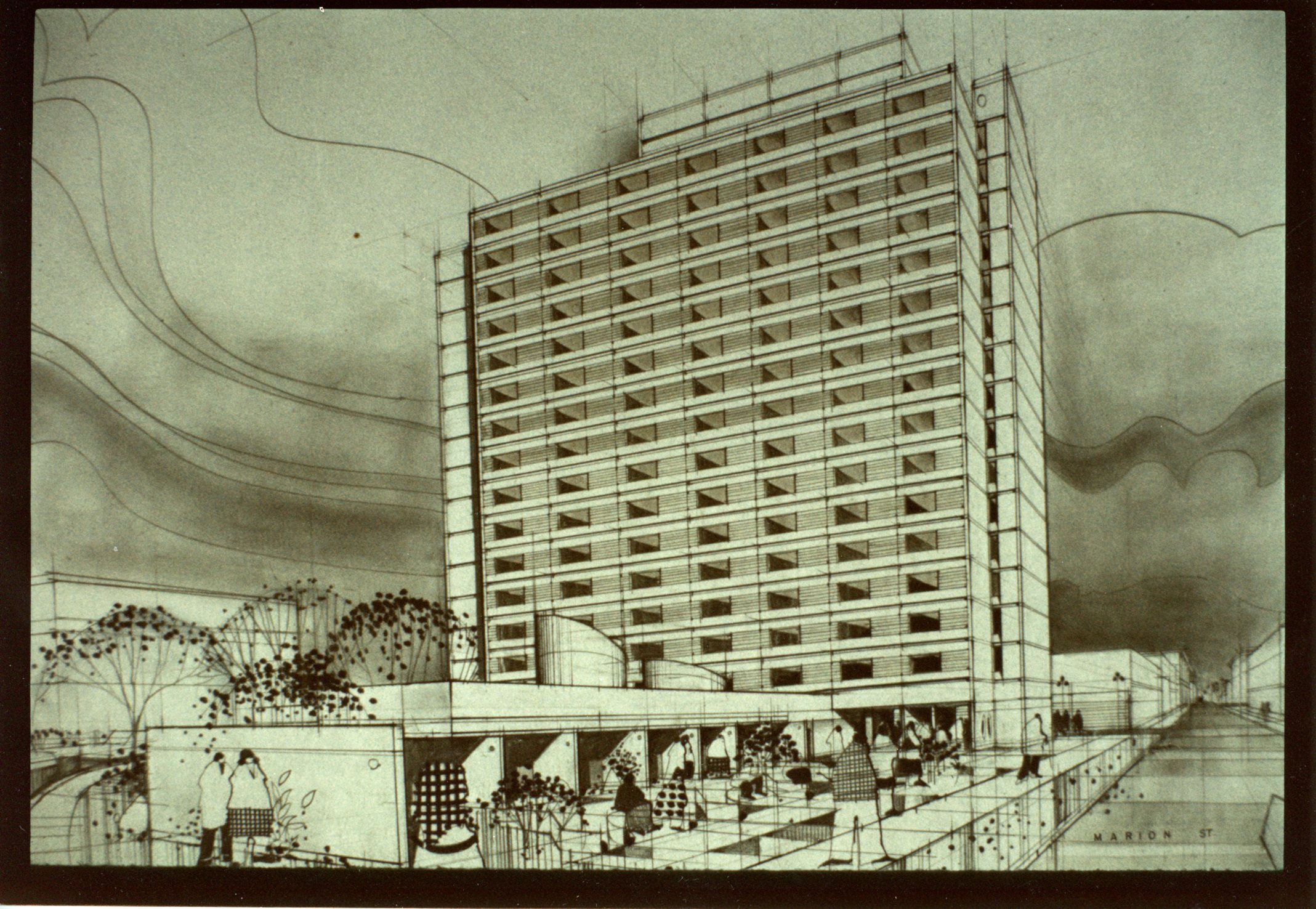

In 1968 Roy became a founding partner of IKOY, a renowned architectural firm founded by partners Roy Izen (I), Ron Keenberg (K), Stan Osaka (O), and Jim Yamashita (Y).10 That same year, IKOY designed Winnipeg’s “first high-income, large-suite, high-rise apartment,” the award-winning Hampton Green building, as well as a new interior for the University of Manitoba’s Student Union Building.11 The firm won dozens of awards throughout Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in its first years of operation.12 Roy left the firm to pursue other opportunities in 1973.

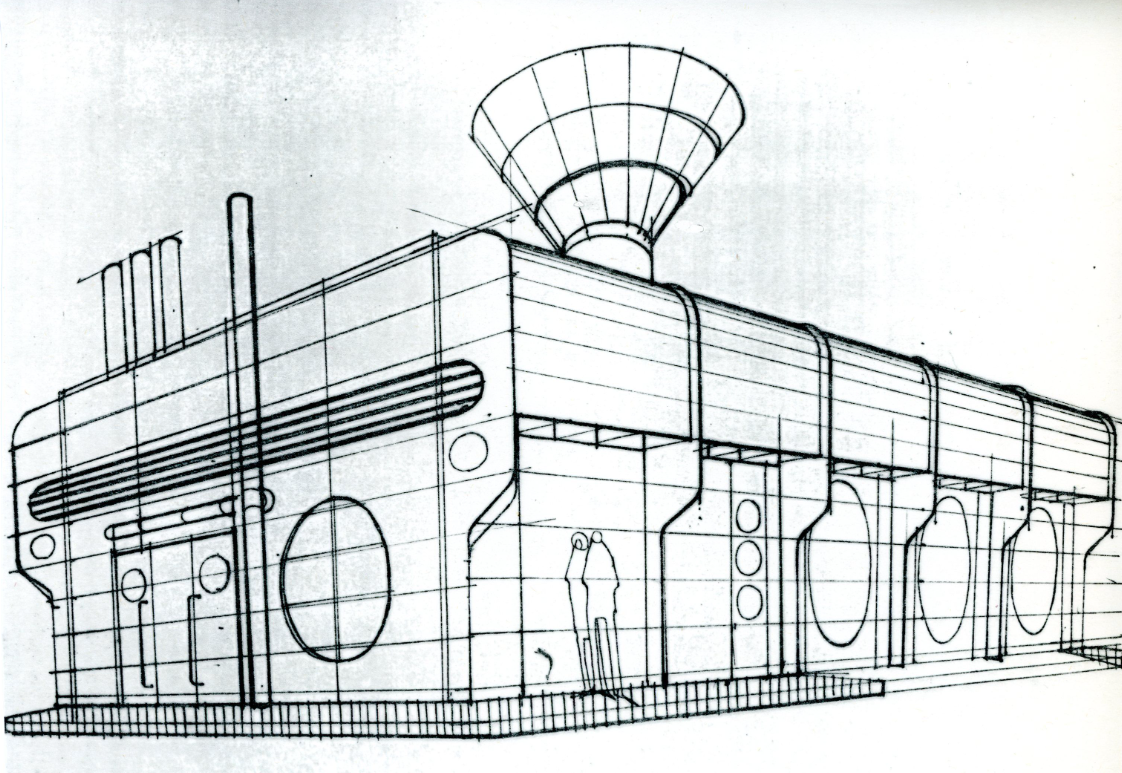

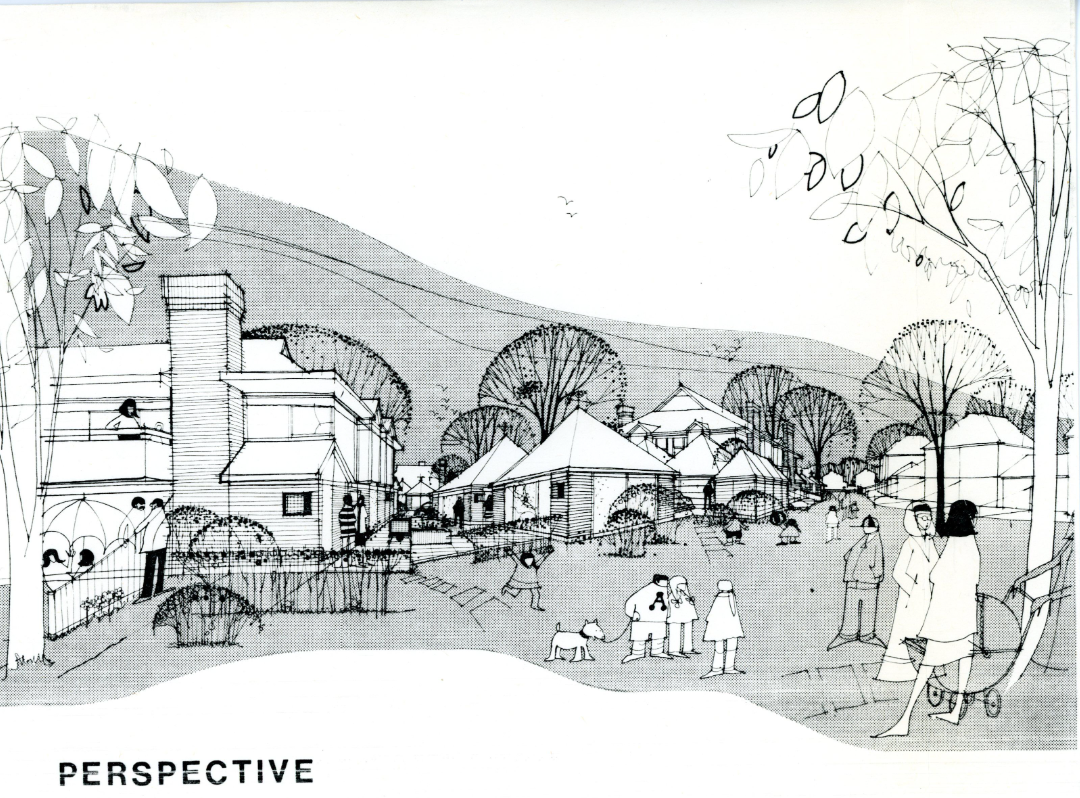

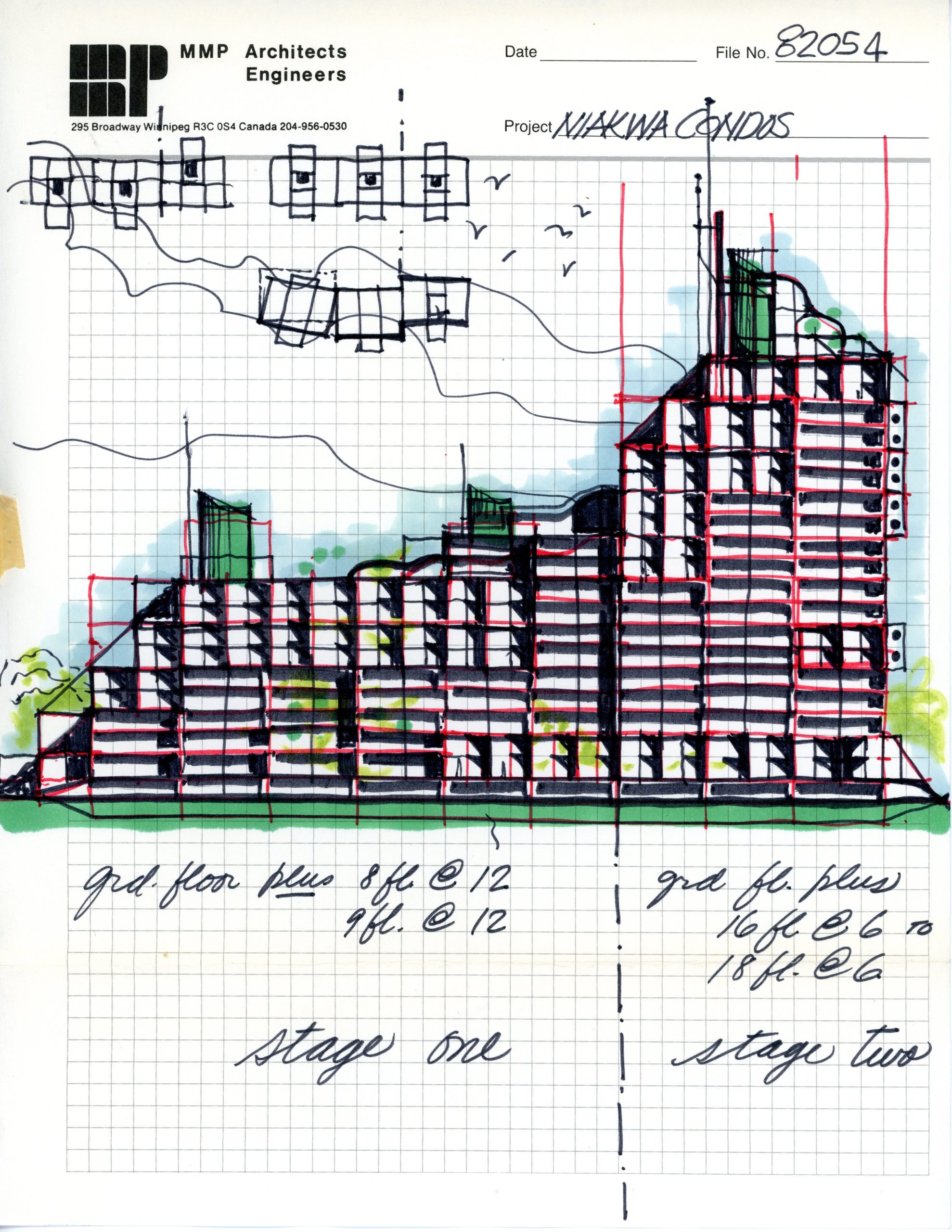

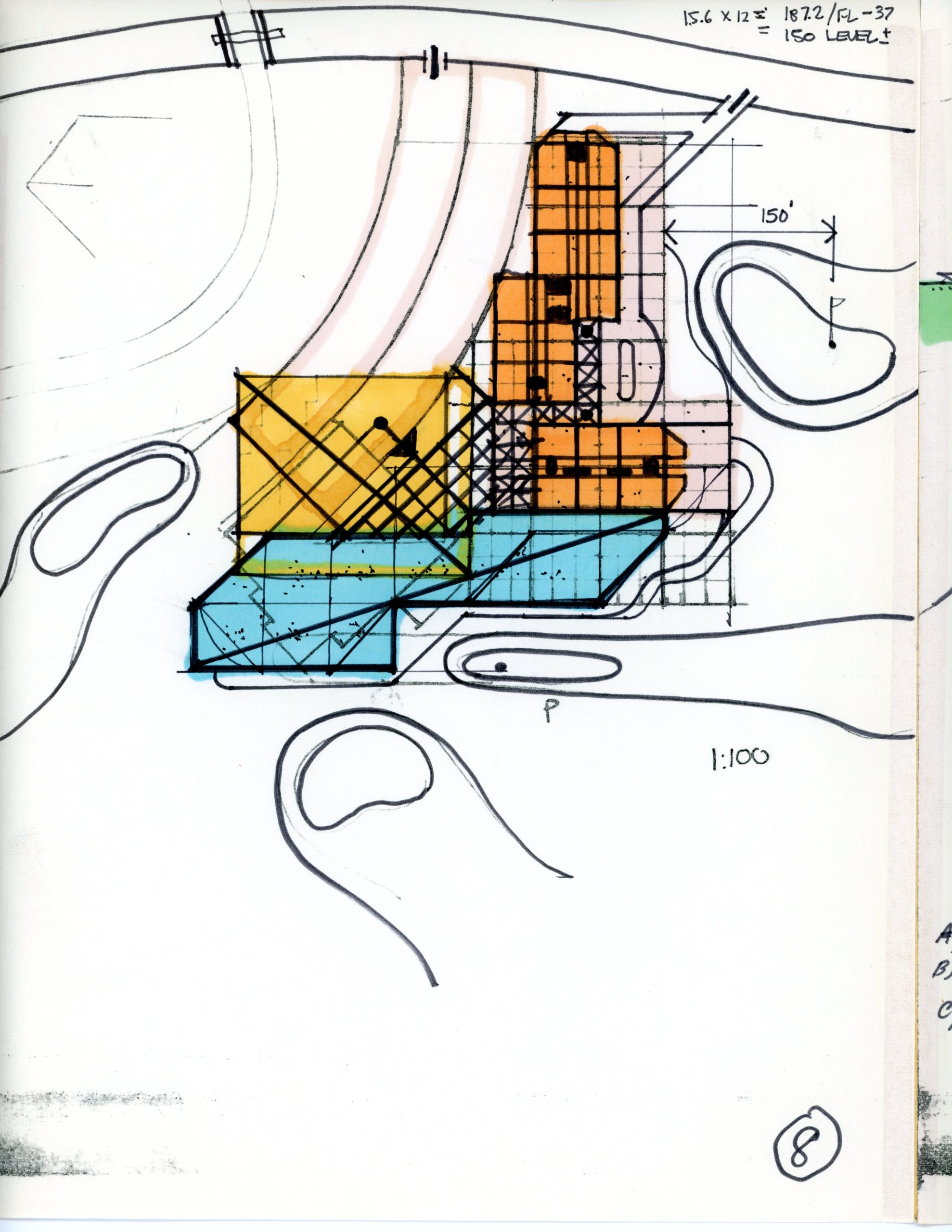

After leaving IKOY, Roy worked for ten years as a Senior Design Associate for Moody Moore and Partners Architects. He then worked for the Federal Government from 1984 to 1997, working first as a Design Architect for the Department of National Defense, then as Chief Design Architect for Public Works and Government Services Canada/Building Product Sector, and finally as Chief of Architectural Services for Public Works and Government Services Canada/Real Property Services. In 1997, he opened his own firm, J. Roy Izen. He served as Principal Architect until his retirement in 1999.

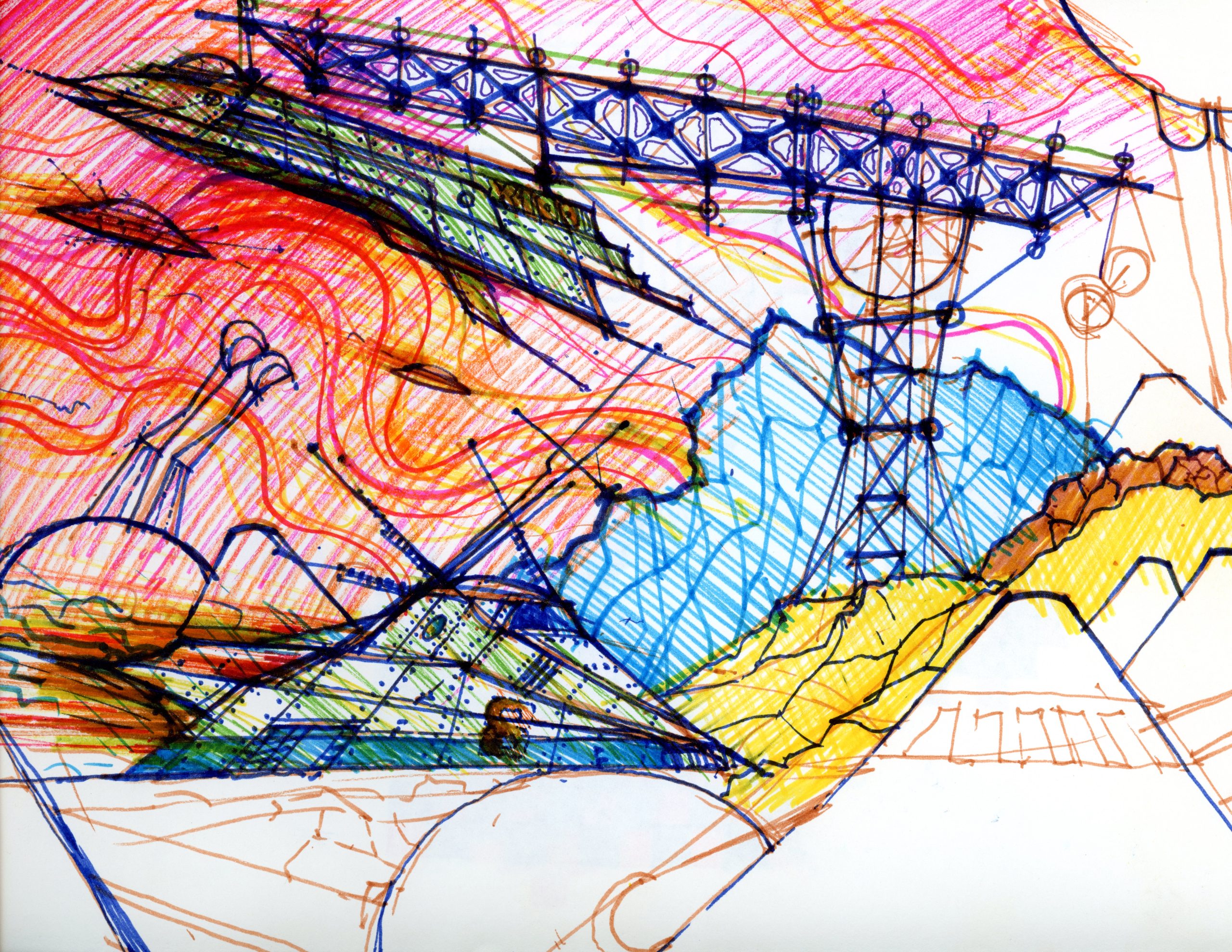

Roy married Barbara Galpern at the Shaarey Zedek Synagogue in April of 1961.13 The couple had three sons; Michael, Steven, and Jon. The family was raised in Winnipeg, living at 359 Ash Street in a home filled with artworks painted by Roy. His son Jon remembers him working at the dining room table late into the night, covering the table completely in designs. He was often working intently on a seemingly minor detail, as he believed firmly that “The Devil is in the details” and often said that “The last thing you do is the first thing you see.”14

Roy’s appreciation for architectural details carried on into a love of photography. He often took long walks through cities, snapping pictures of unassuming fragments of the urban landscape like “staircases, loading docks, and sections of buildings that folded over one another.”

Another passion of Roy’s was painting. He loved to create colour studies, and if he saw a painting that he enjoyed at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, he rented it, brought it home, and painted a copy.

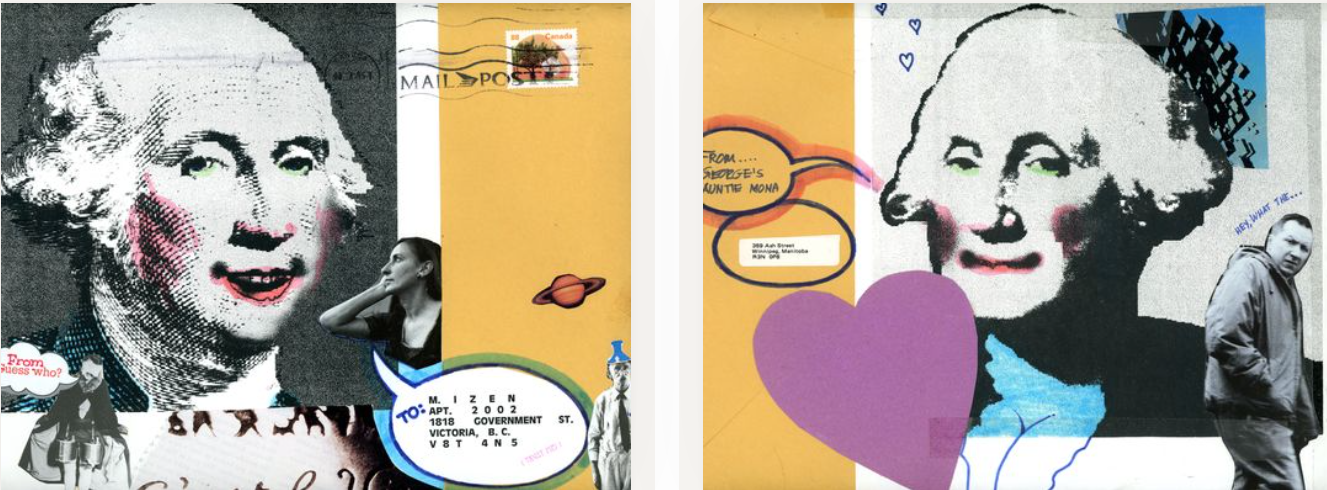

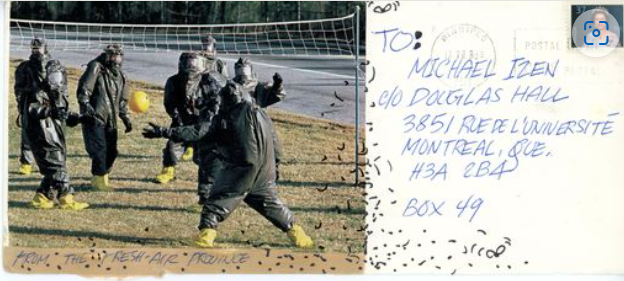

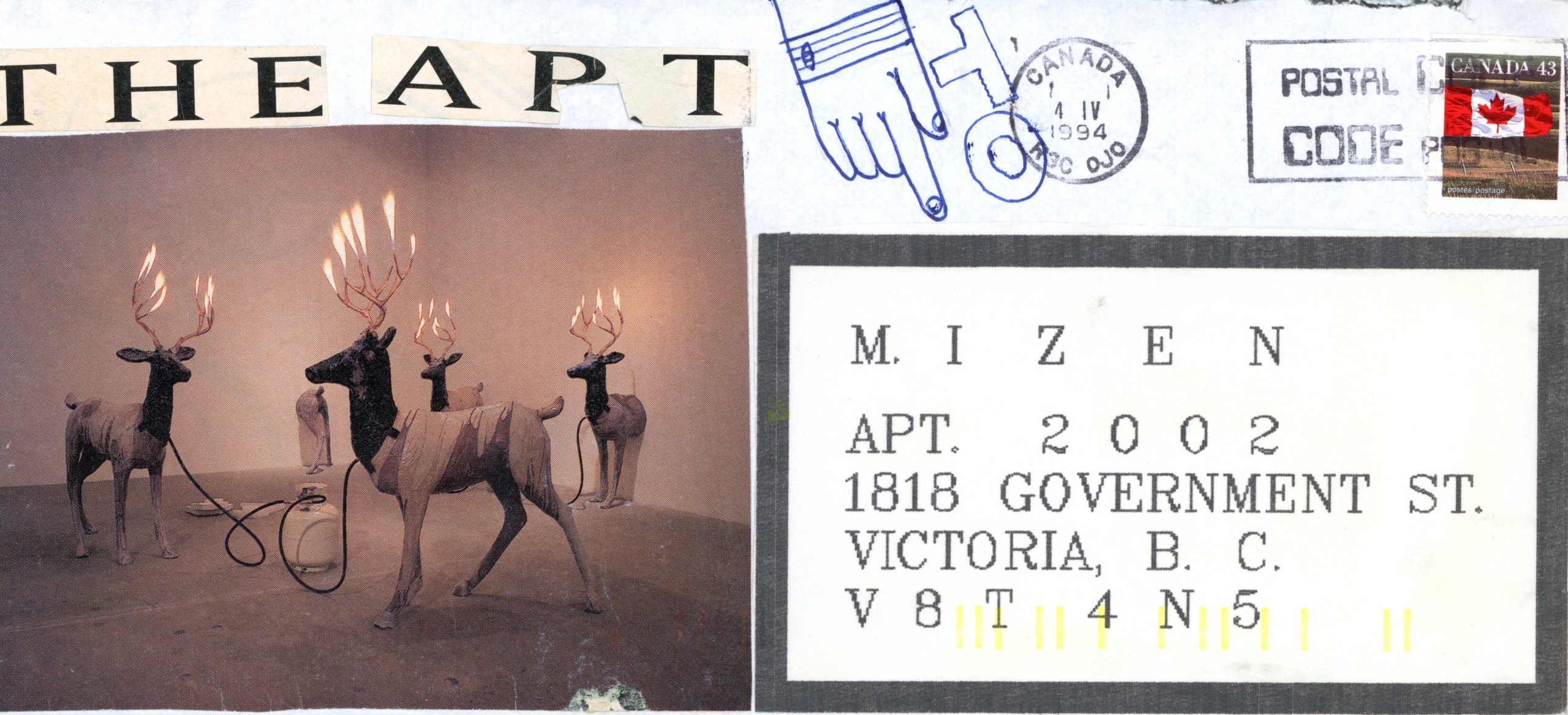

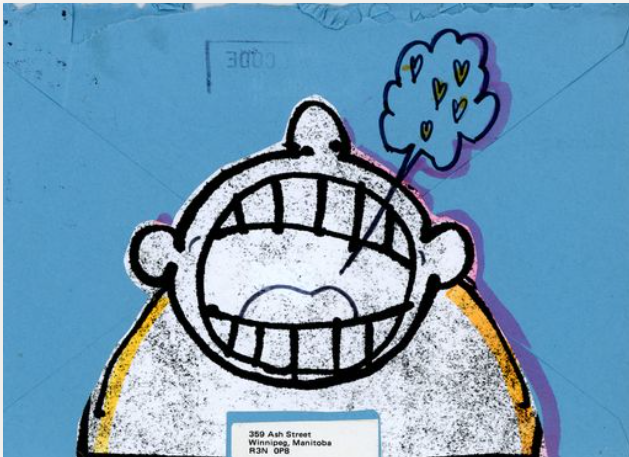

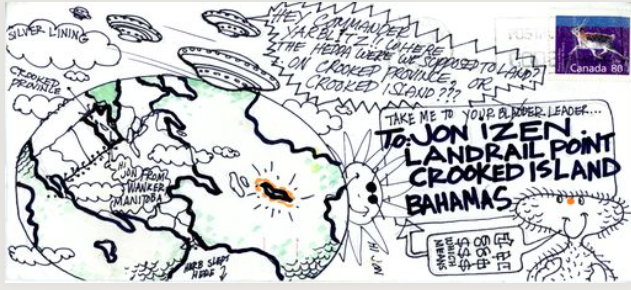

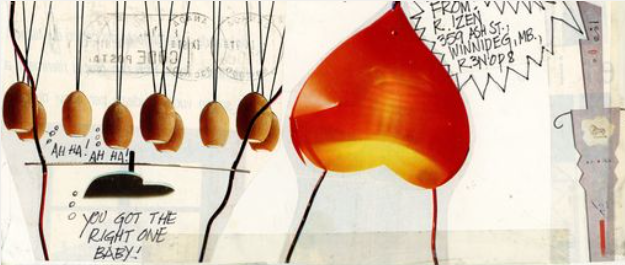

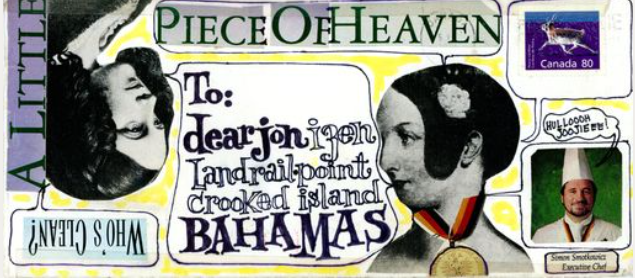

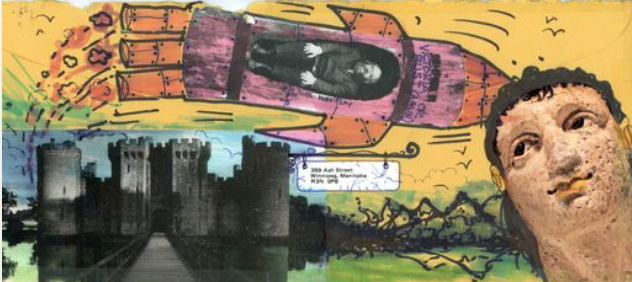

When Roy’s sons grew up and moved away, he kept in touch with them via letters which he sealed in envelopes decorated with drawings and collages. The envelopes are arresting works of art, some psychedelic, some moving, and often featuring funny texts. Mail carriers commented that they looked forward to seeing each new envelope.15 The envelopes number in the hundreds and attest to Roy’s creativity, visual artistry, as well as to his devotion to his sons. Upon their retirement, Roy and Barbara moved to British Columbia to be nearer to their sons.

Throughout his life, Roy’s love of art helped him to process periods of suffering. In 2012, Roy’s son Michael was diagnosed with an aggressive prostate cancer. Determined to find the funny side to a sad situation, Michael chose to write a book about his experience living with terminal cancer, which is filled with frank, unflinching humor. Roy and his youngest son Jon contributed the illustrations to the book, called “Finger Up the Bum: A Guide to My Prostate Cancer.” Roy is credited on the cover of the book as J. Roy “Sneeze” Izen. Although Roy was hesitant about the project at first, the Izens collaboration on the book brought them much needed levity during a challenging time. Michael passed away on August 26th, 2018.

Michael’s death and the onset of illness prompted Roy and Barbara to move into the home of their youngest son, Jon, in Gibsons, British Columbia. Here Roy once again combatted suffering through art, filling his new home with artworks and expressing himself through drawing as his dementia progressed.

Roy died on January 26th, 2024, at 88 years old.

“My Dad was Brilliant. He had a crazy sense of humour, a super sharp wit, a love of Jeanne’s birthday cake and a strange ability to sing any song published in the 1950s. As well, and perhaps obviously, he was ENDLESSLY obsessed with architecture and design.16” – Jon Izen, Roy’s son.