The History of Central Park

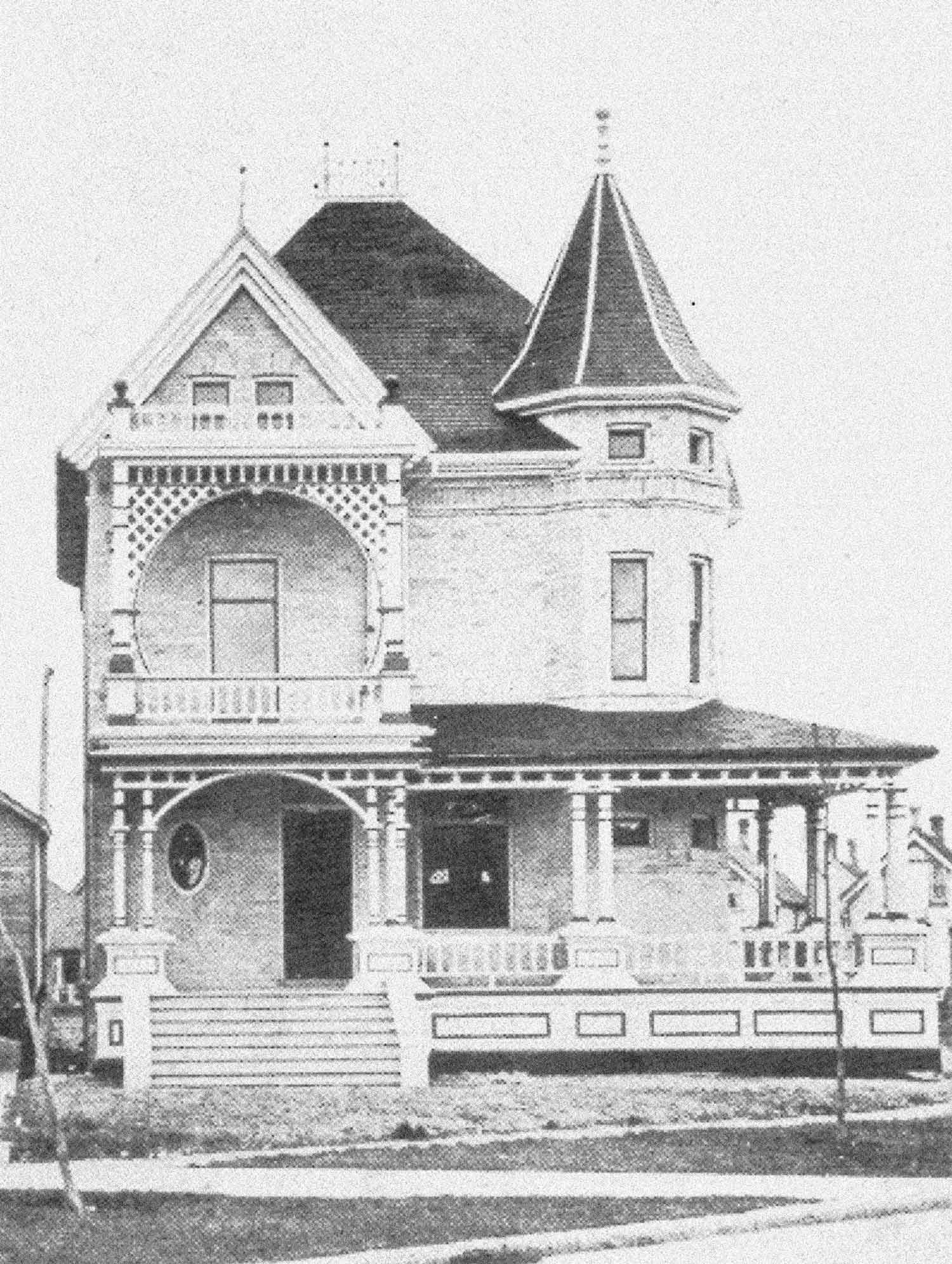

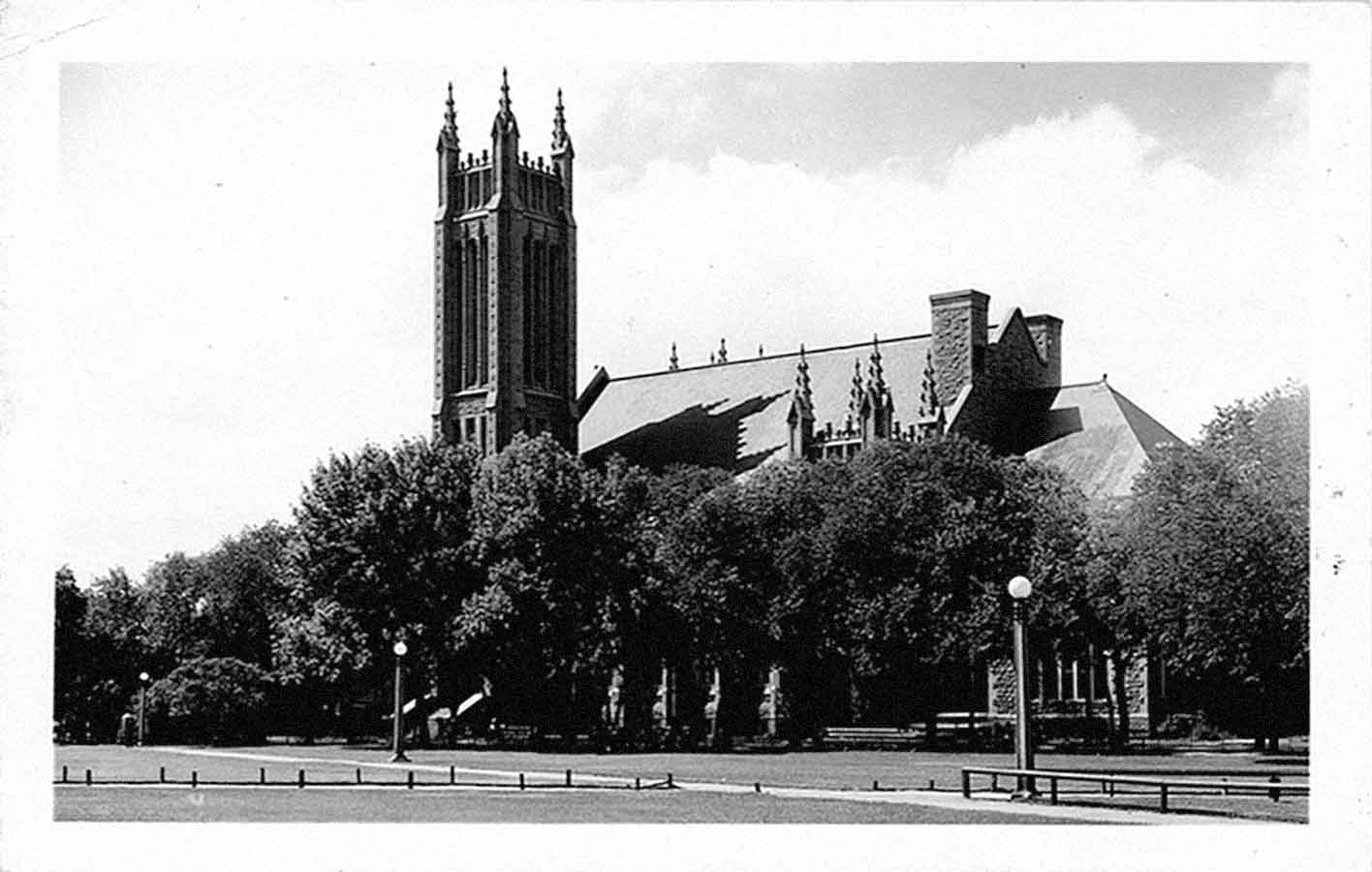

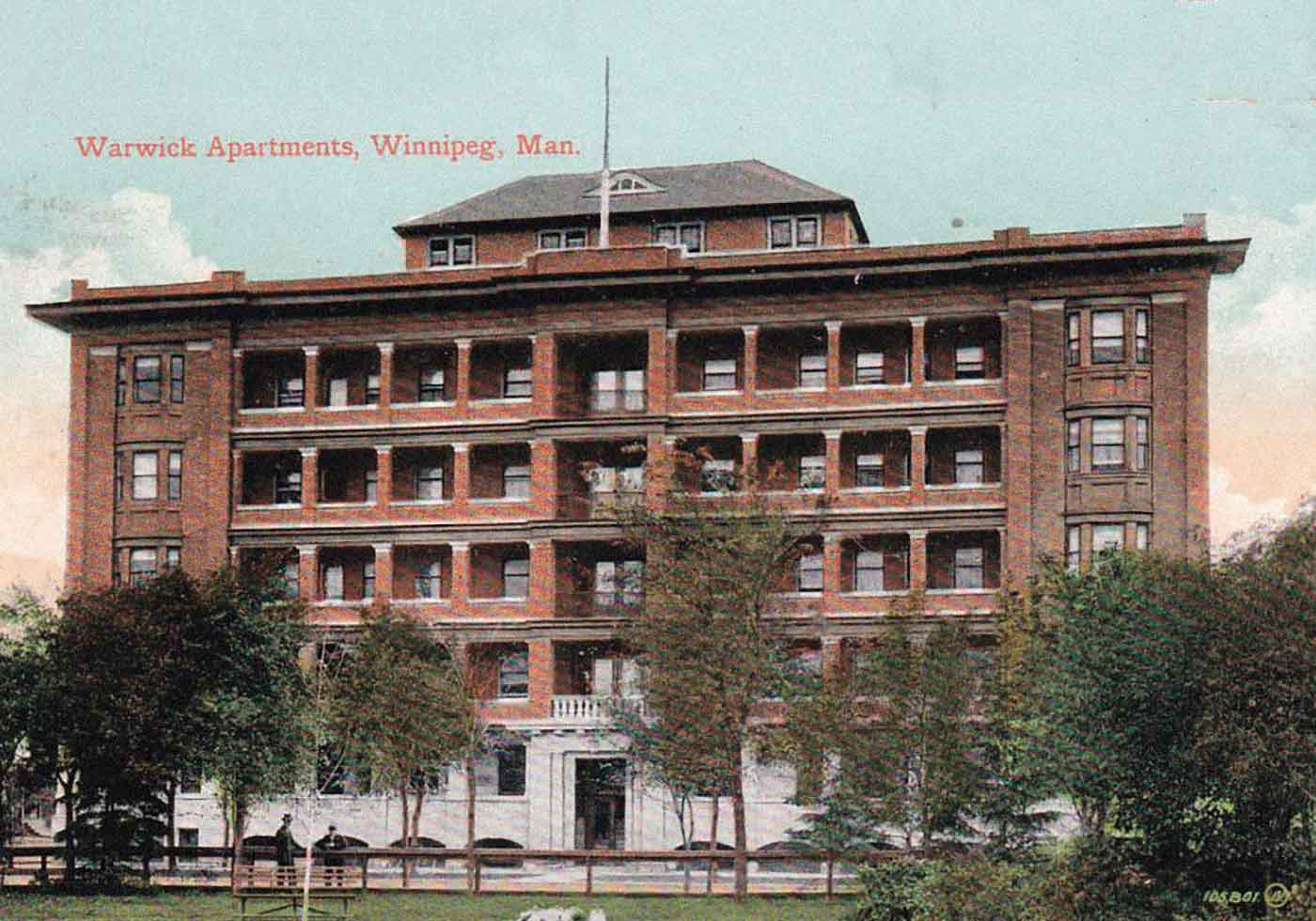

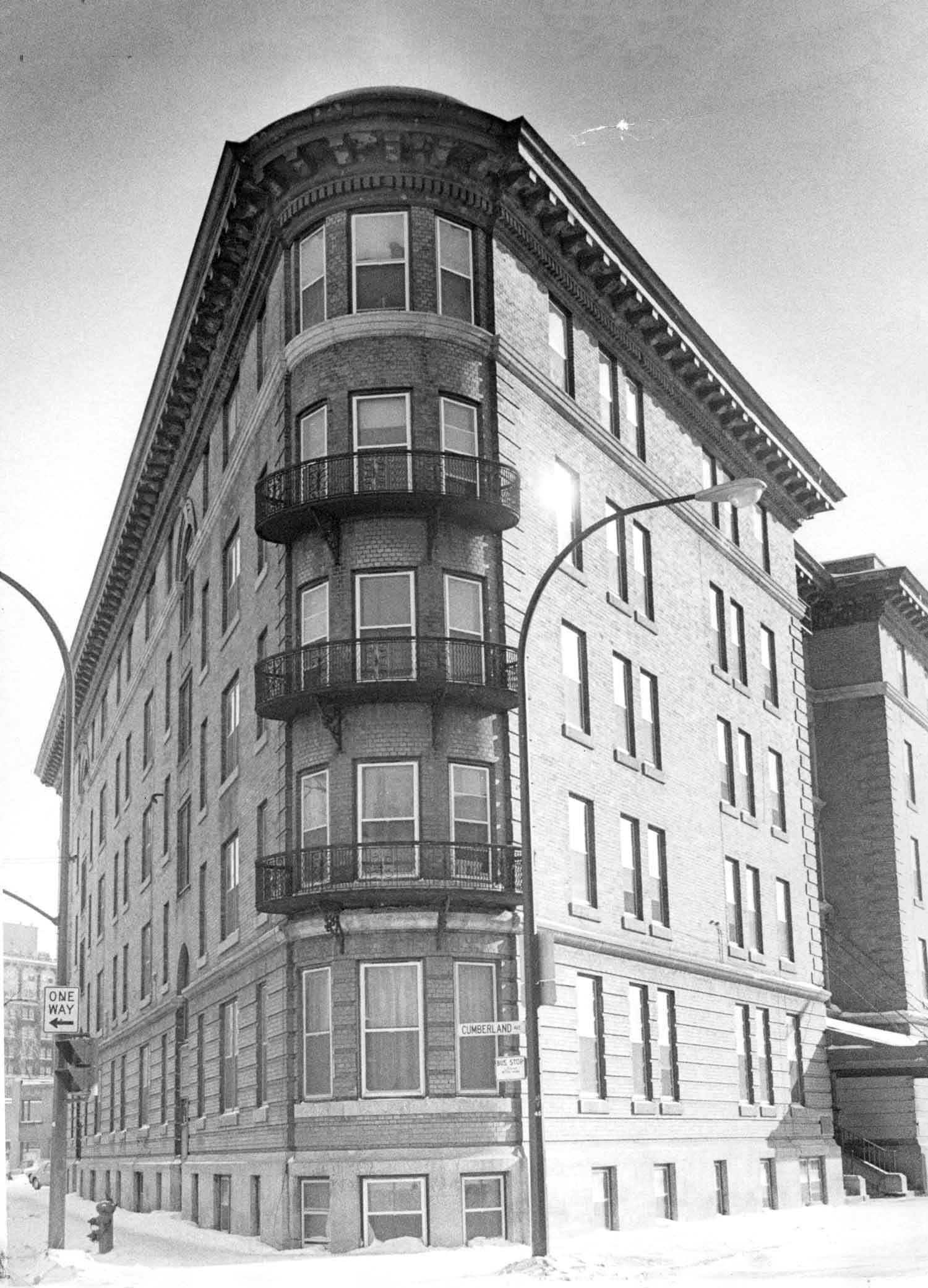

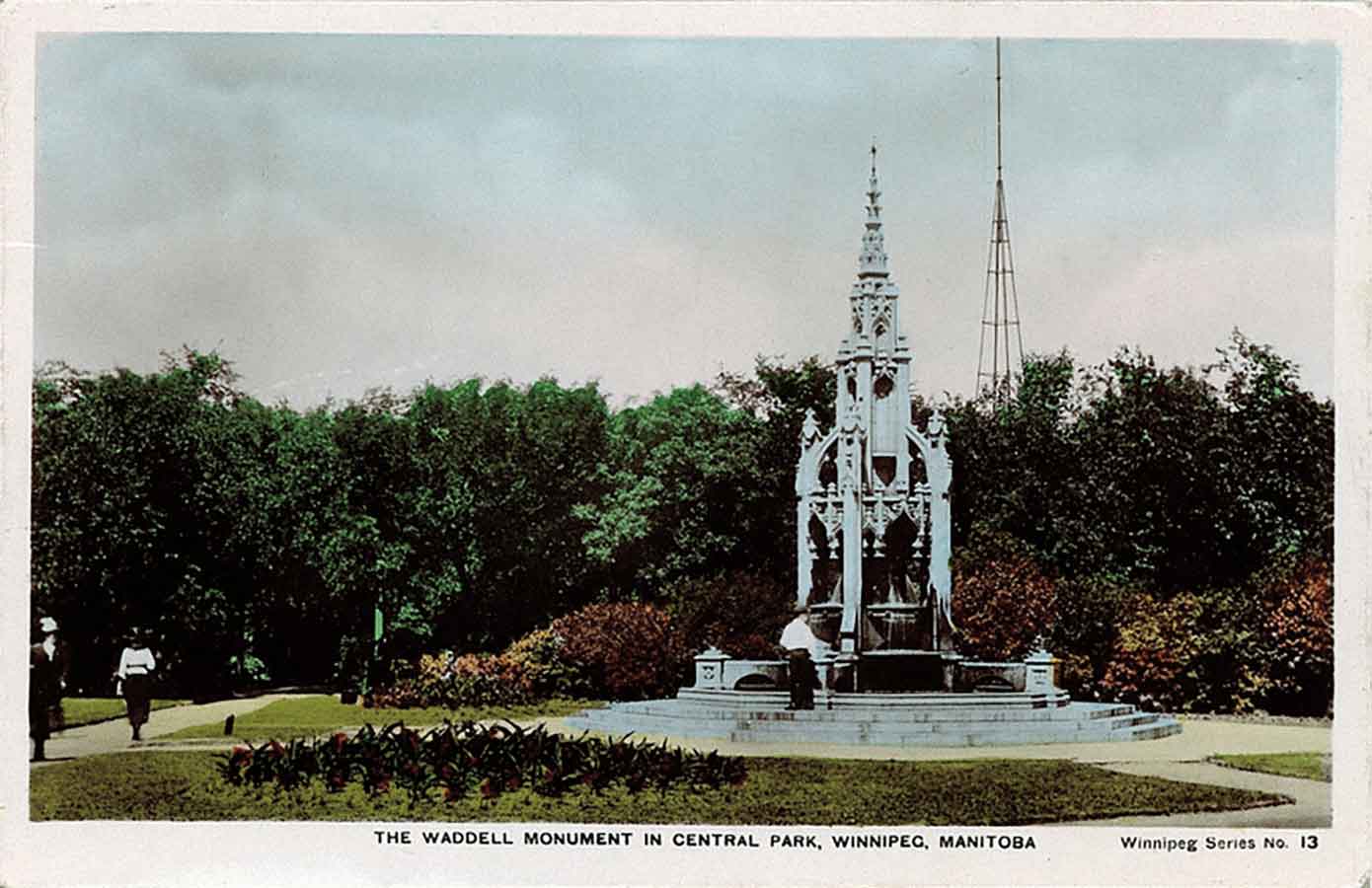

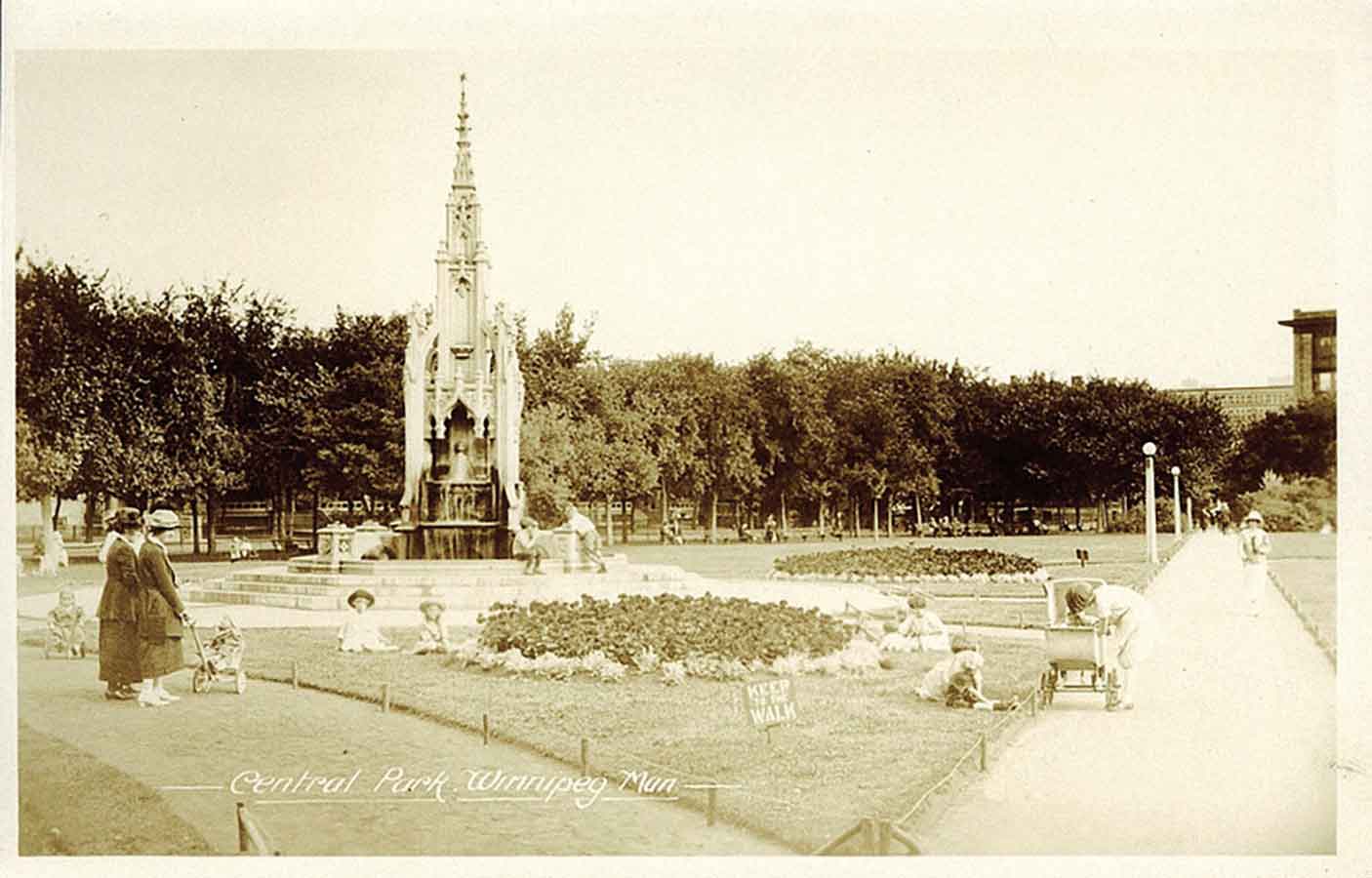

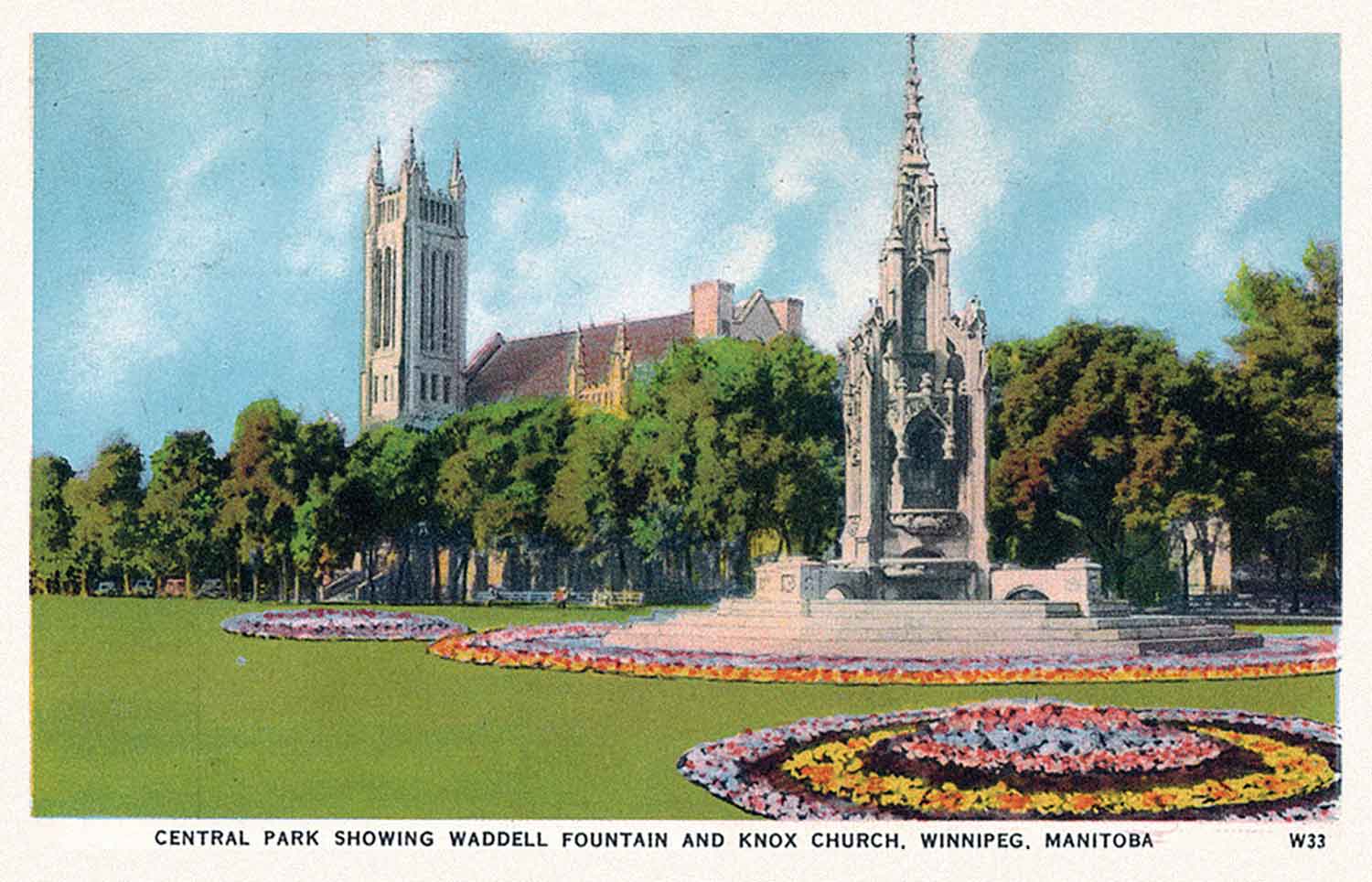

The year 1893 was exciting in Winnipeg. The newly formed Public Parks Board bought property to create Winnipeg’s first four parks. When the land was purchased, the City did not refer to the areas as parks; instead, they called them “ornamented squares or breathing centres.” One of these ornamented squares was Central Park, which was purchased from the Hudson’s Bay Company for $20,000.

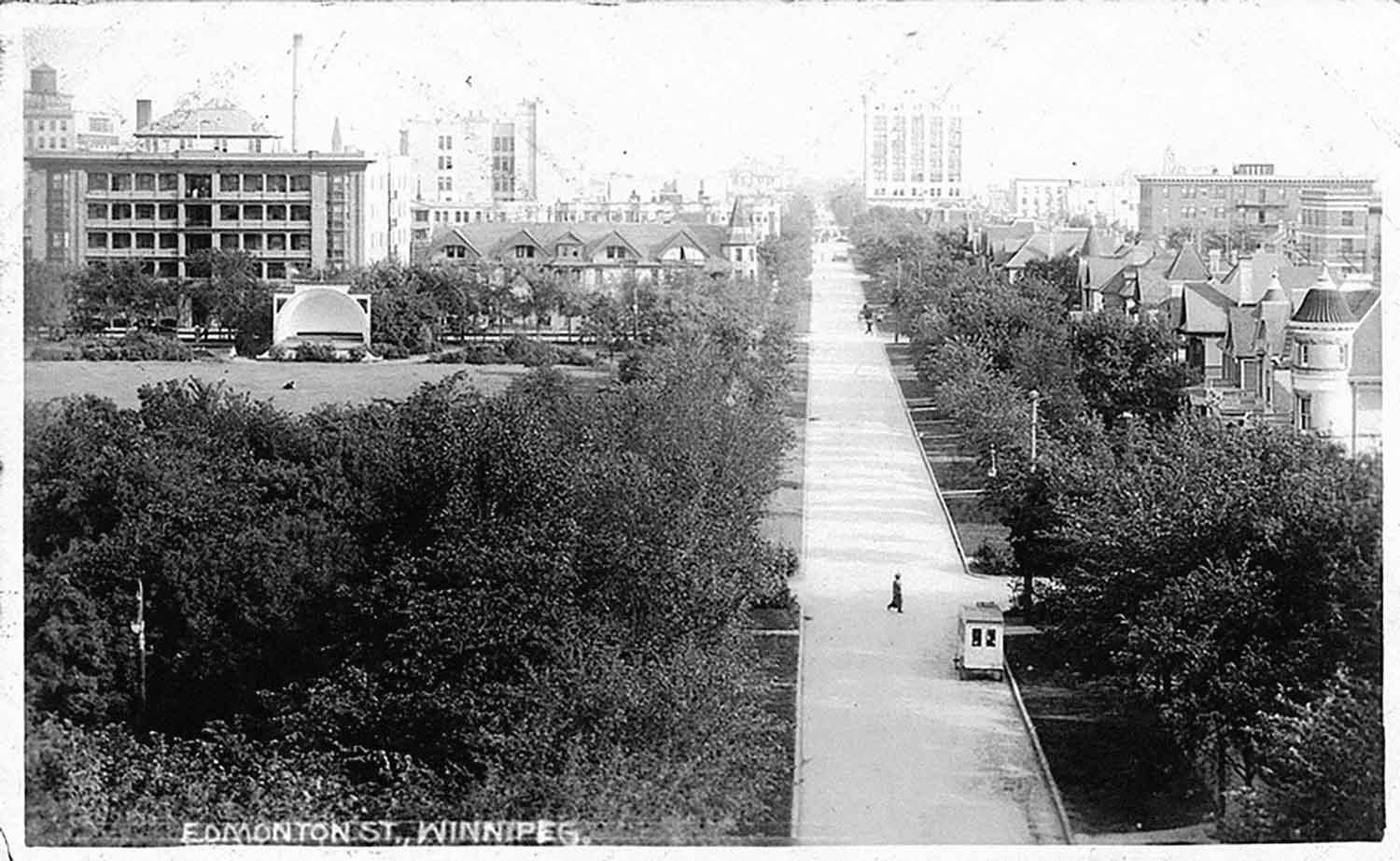

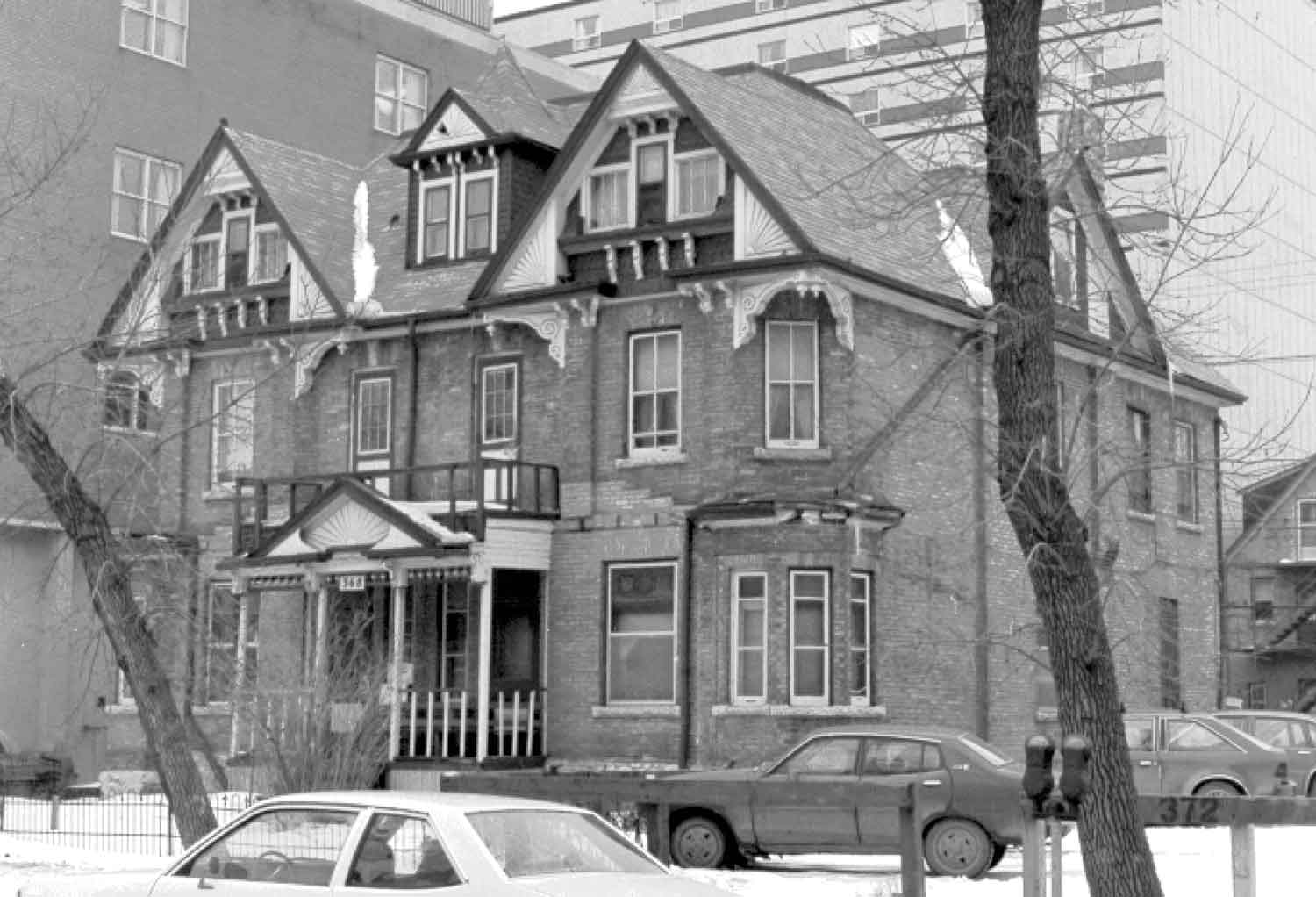

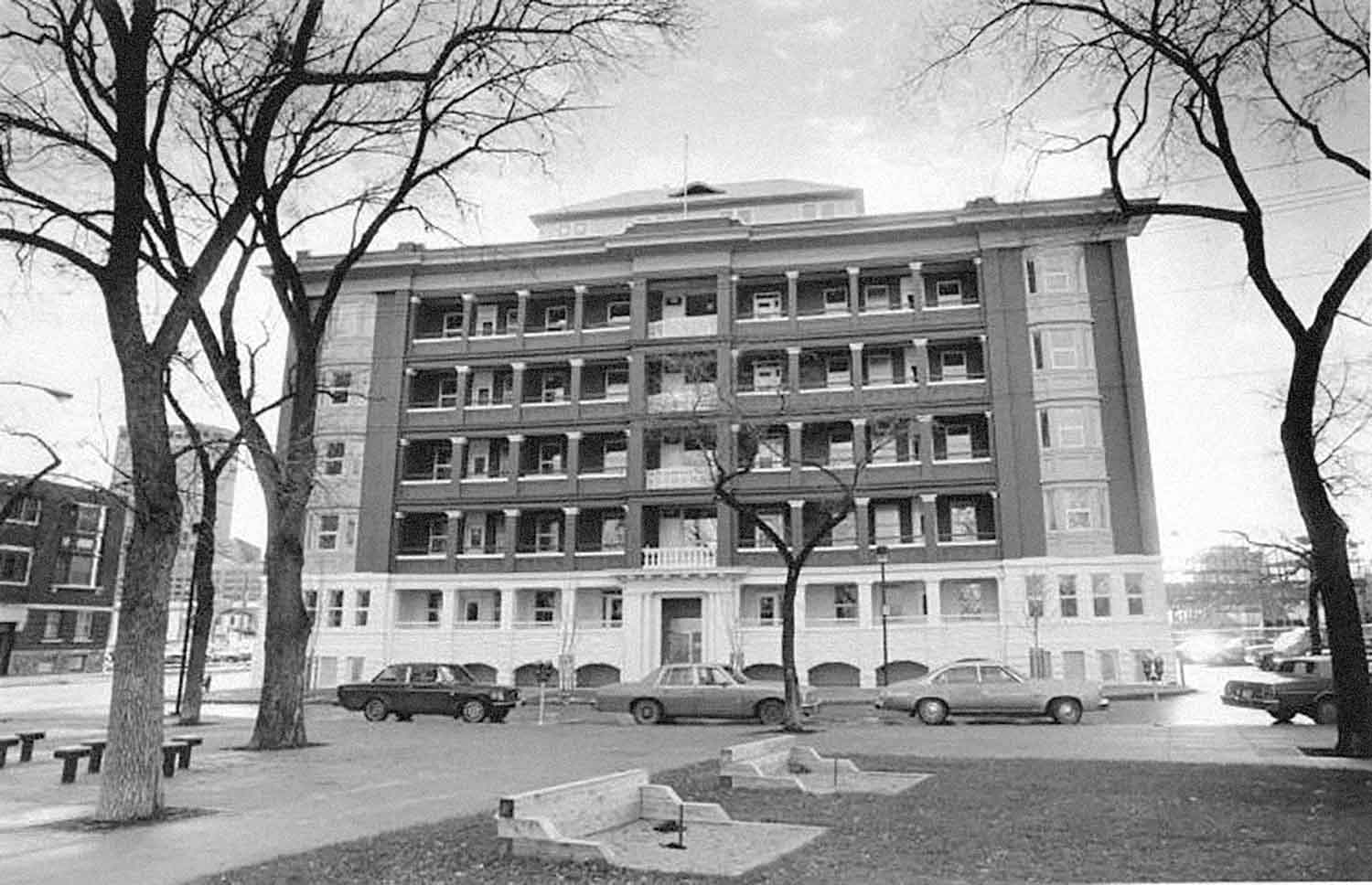

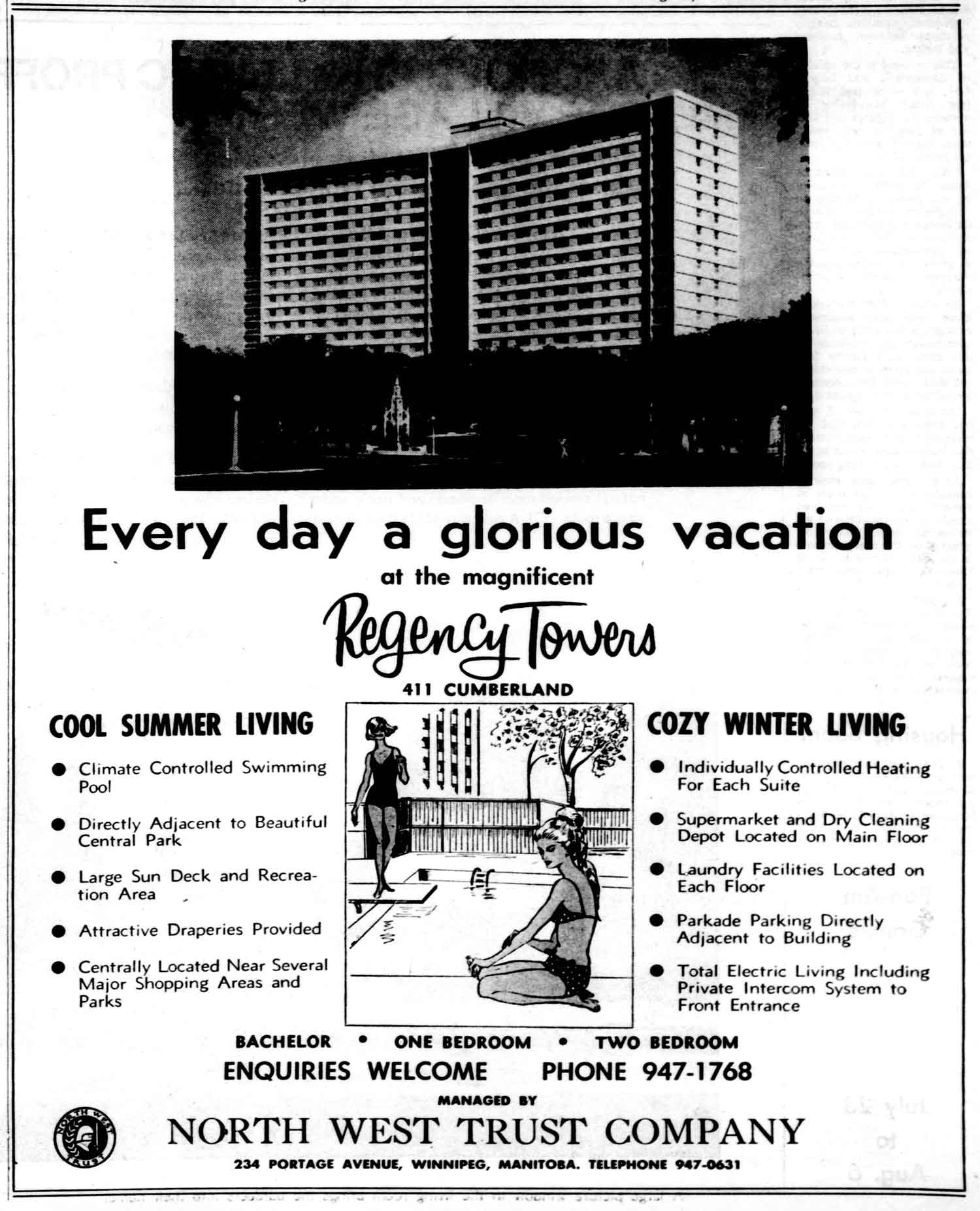

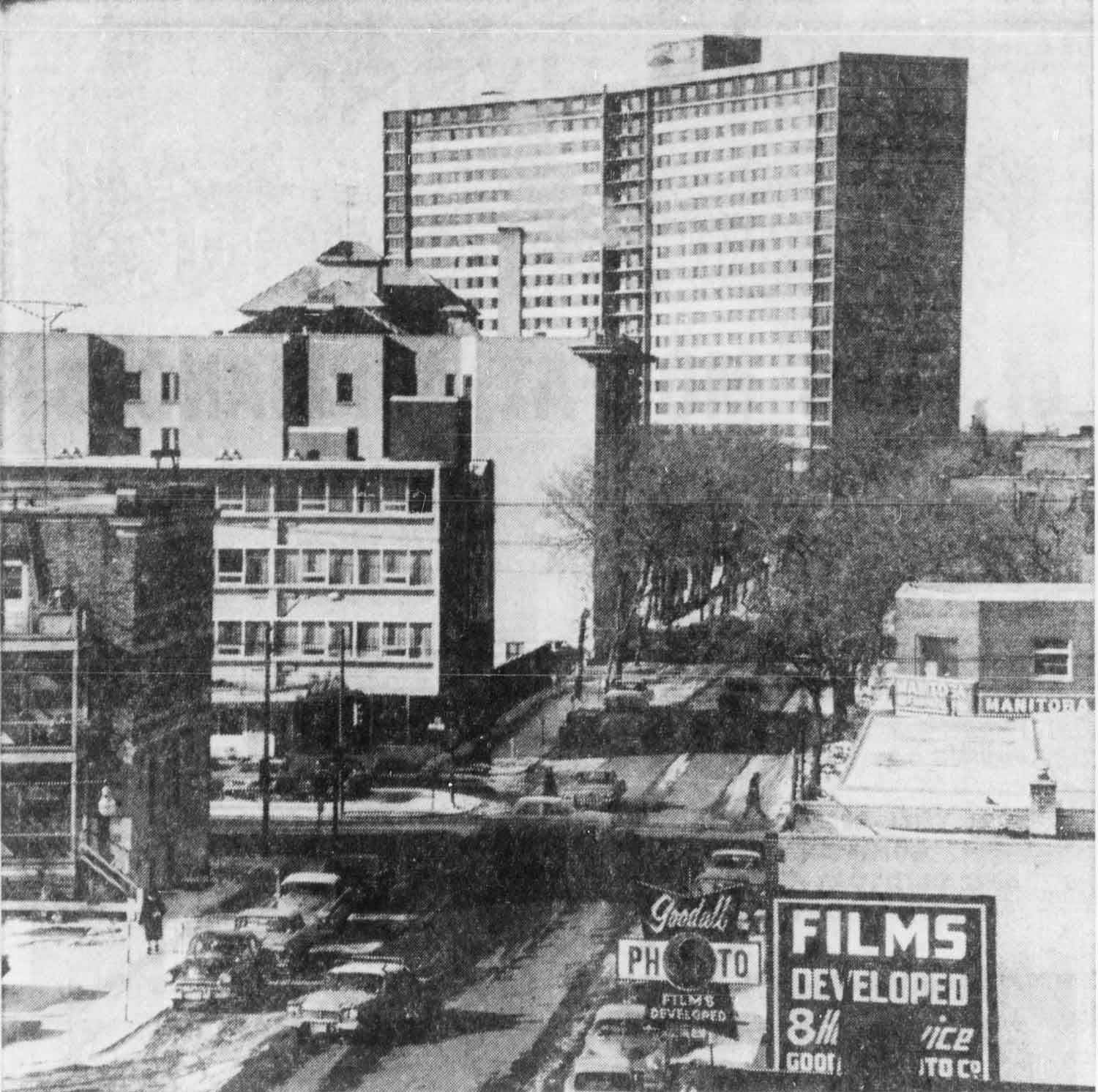

Central Park gained popularity quickly, and by the early 1900s the park had a tennis court, a bandshell, and large gardens. It became a popular spot to get away from city life. In fact, Central Park was so well liked in its early years that the city had a difficult time maintaining it. As the number of people living in the area decreased through the 1970s on, so did the popularity of Central Park. Less use led to safety concerns and even fewer people.

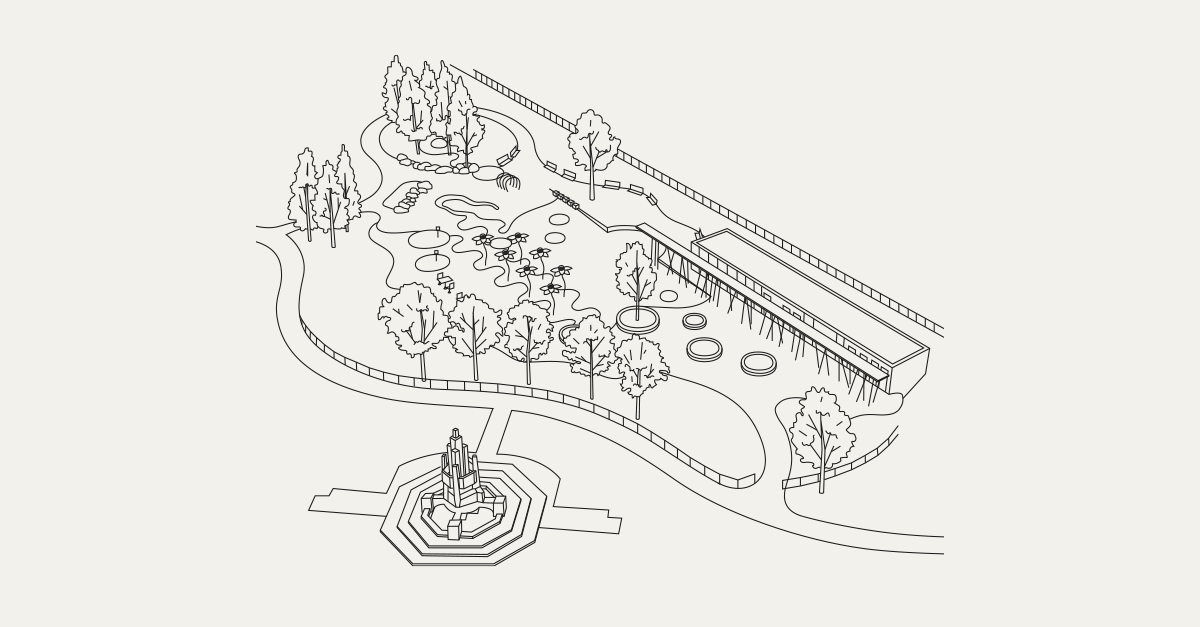

In 2008, the City of Winnipeg launched a major revitalisation of the park. Designed by Scatliff+Miller+Murray and completed in 2012, the project added a wading pool and spray park, an artificial turf, four-season slides, and an interactive sand and water play area with a play structure.

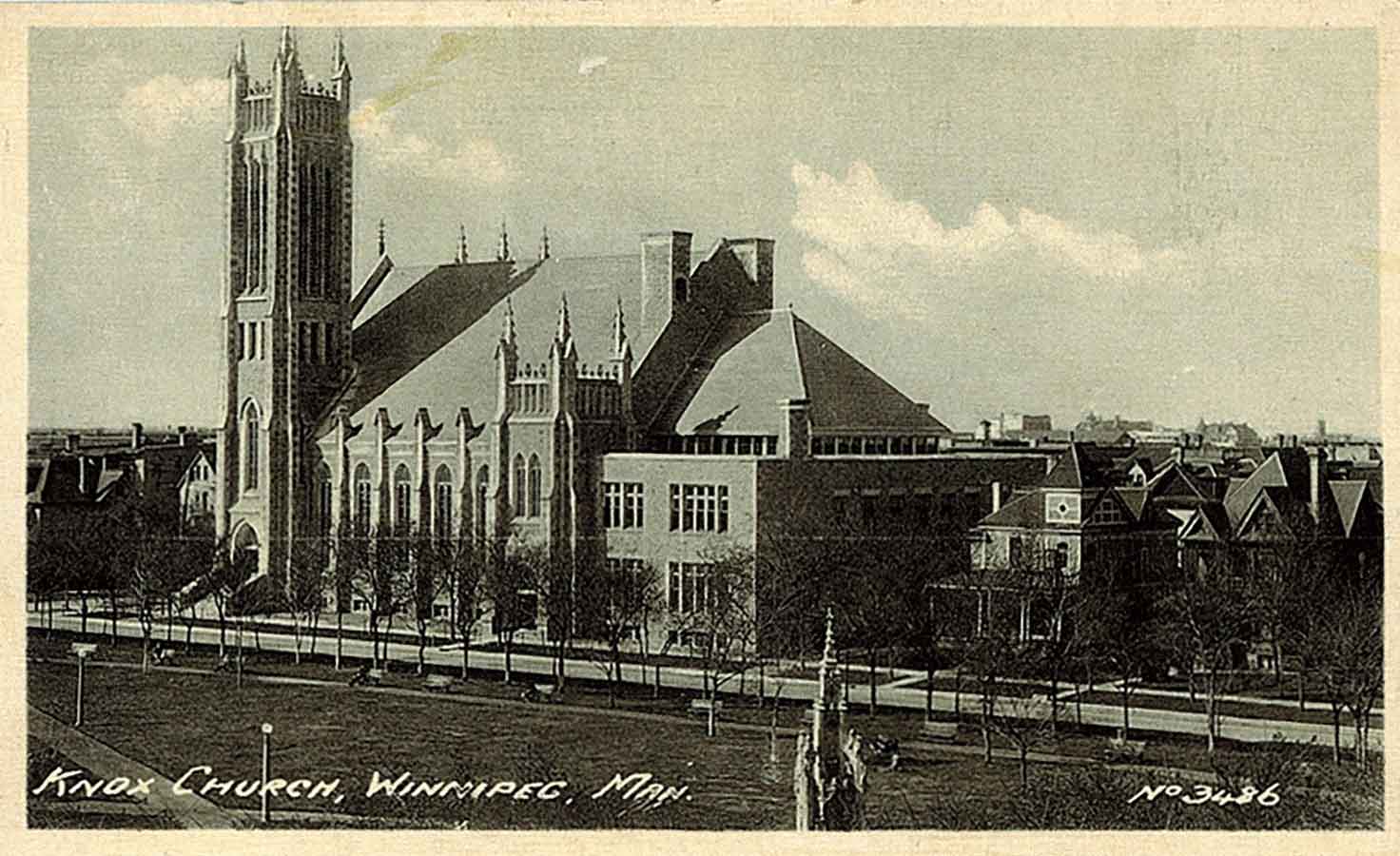

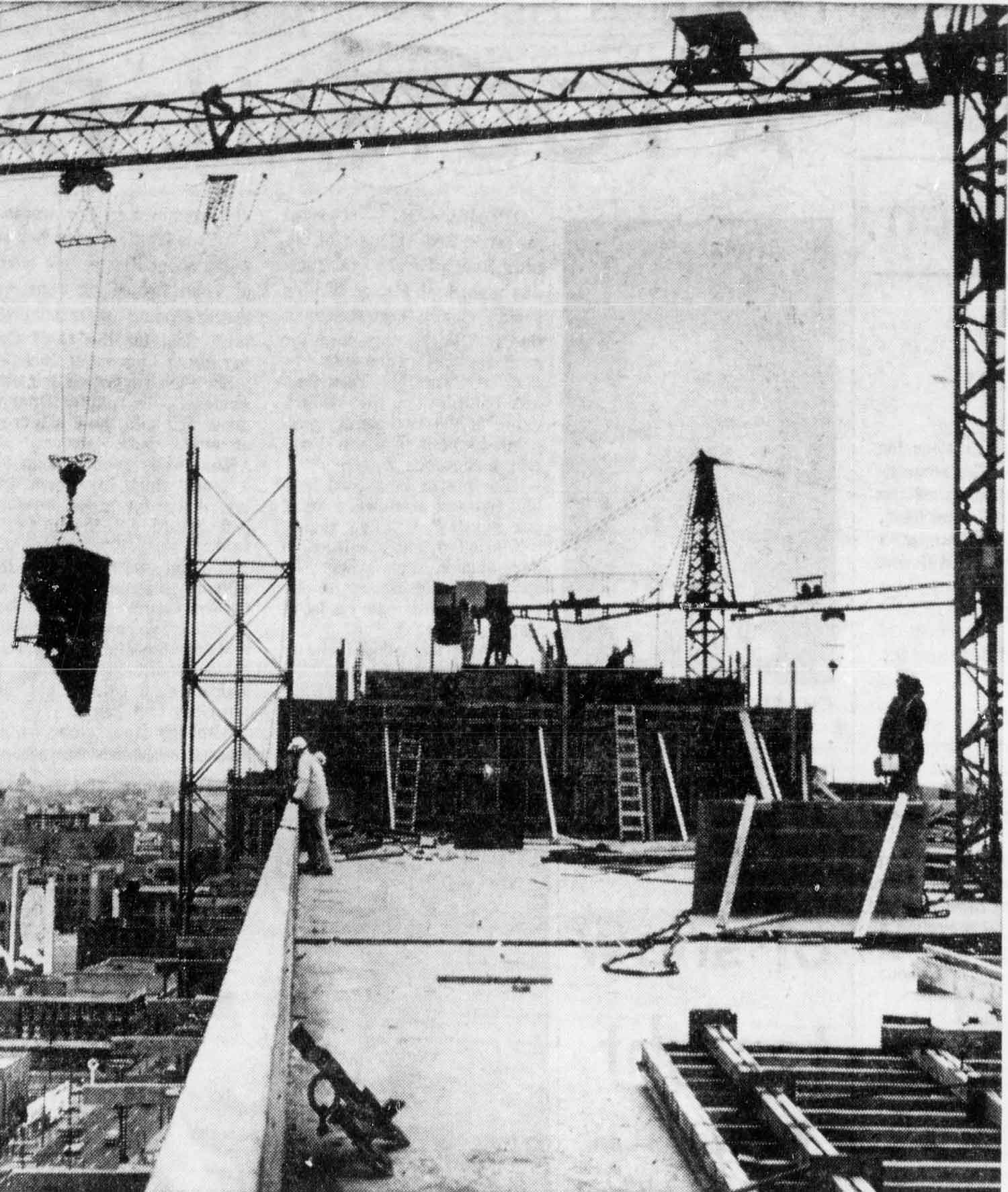

In 1985 the City of Winnipeg’s Department of Environment Planning hired the landscape architecture firm David Wagner Associates Inc. to design an extension to Central Park. The purpose of this project was to create a neighbourhood identity for a community that was undergoing revitalisation and change. The expansion of the park closed off a section of Qu’Appelle Street, which allowed for the park to be expanded to Ellice Avenue. The master plan, based on a vision of then mayor Bill Norrie, was to link Central Park to the Legislature grounds. The development of North Portage, and the construction of Portage Place Mall between 1985 and 1987, meant that these further extensions to the park were never realised.