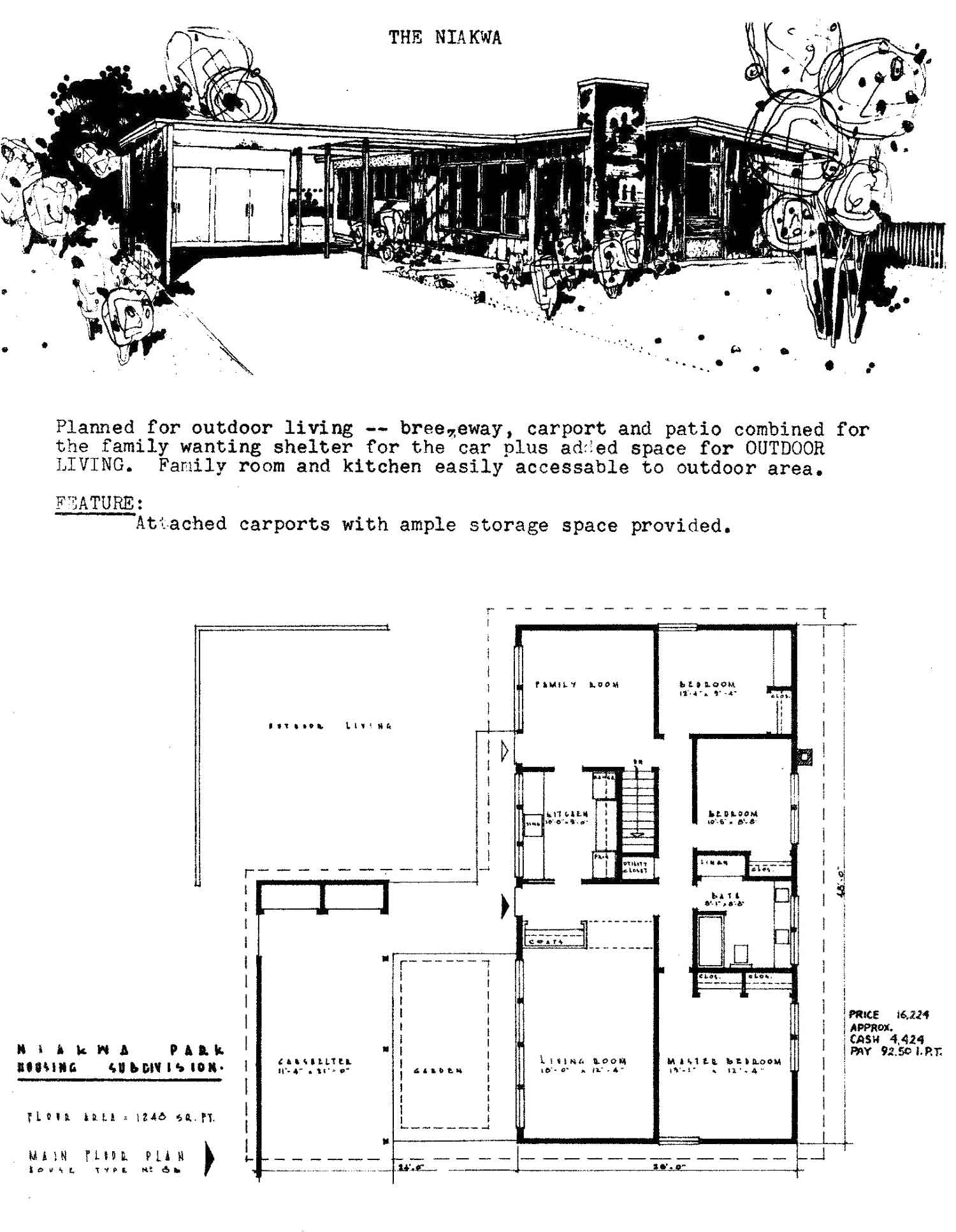

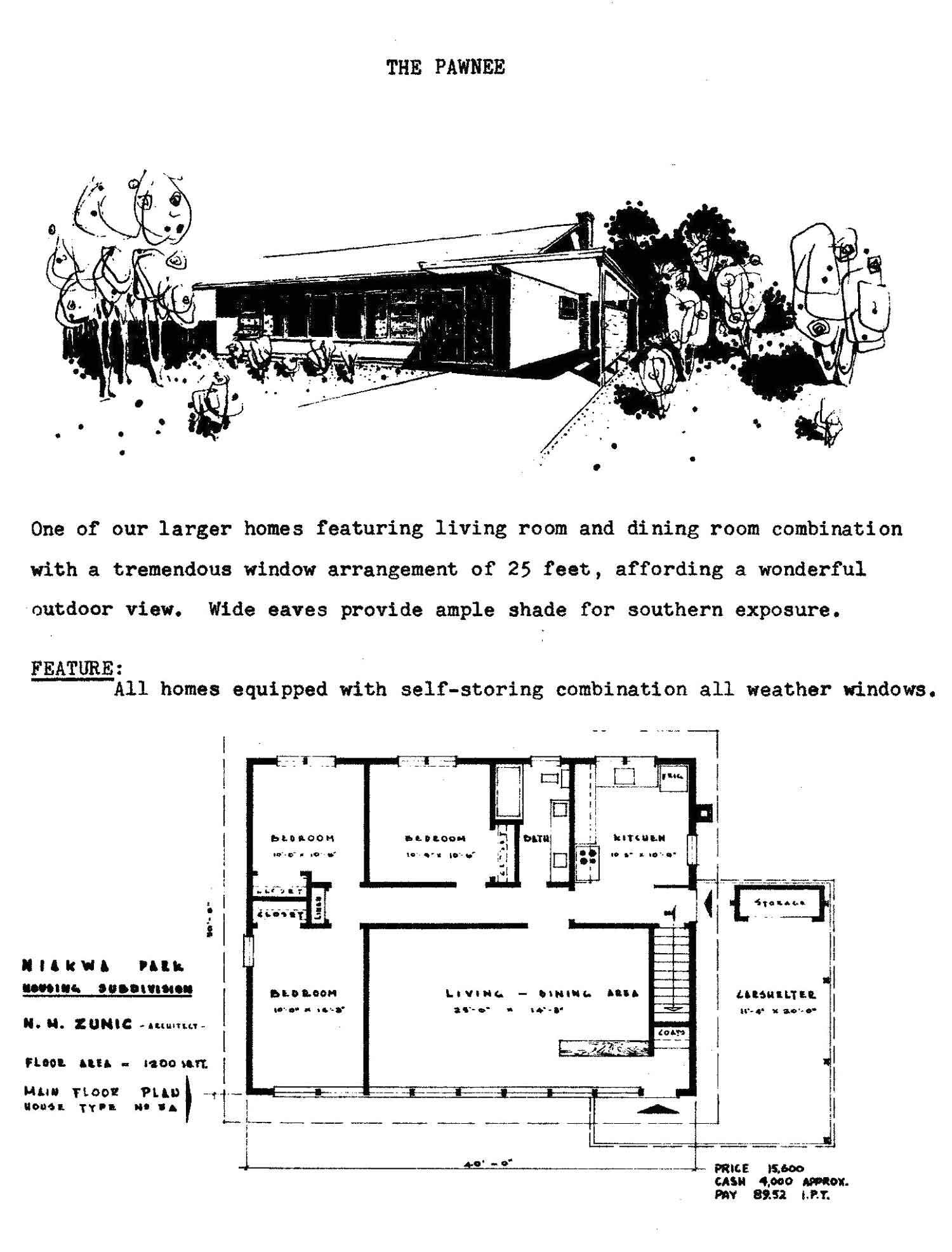

Niakwa Park

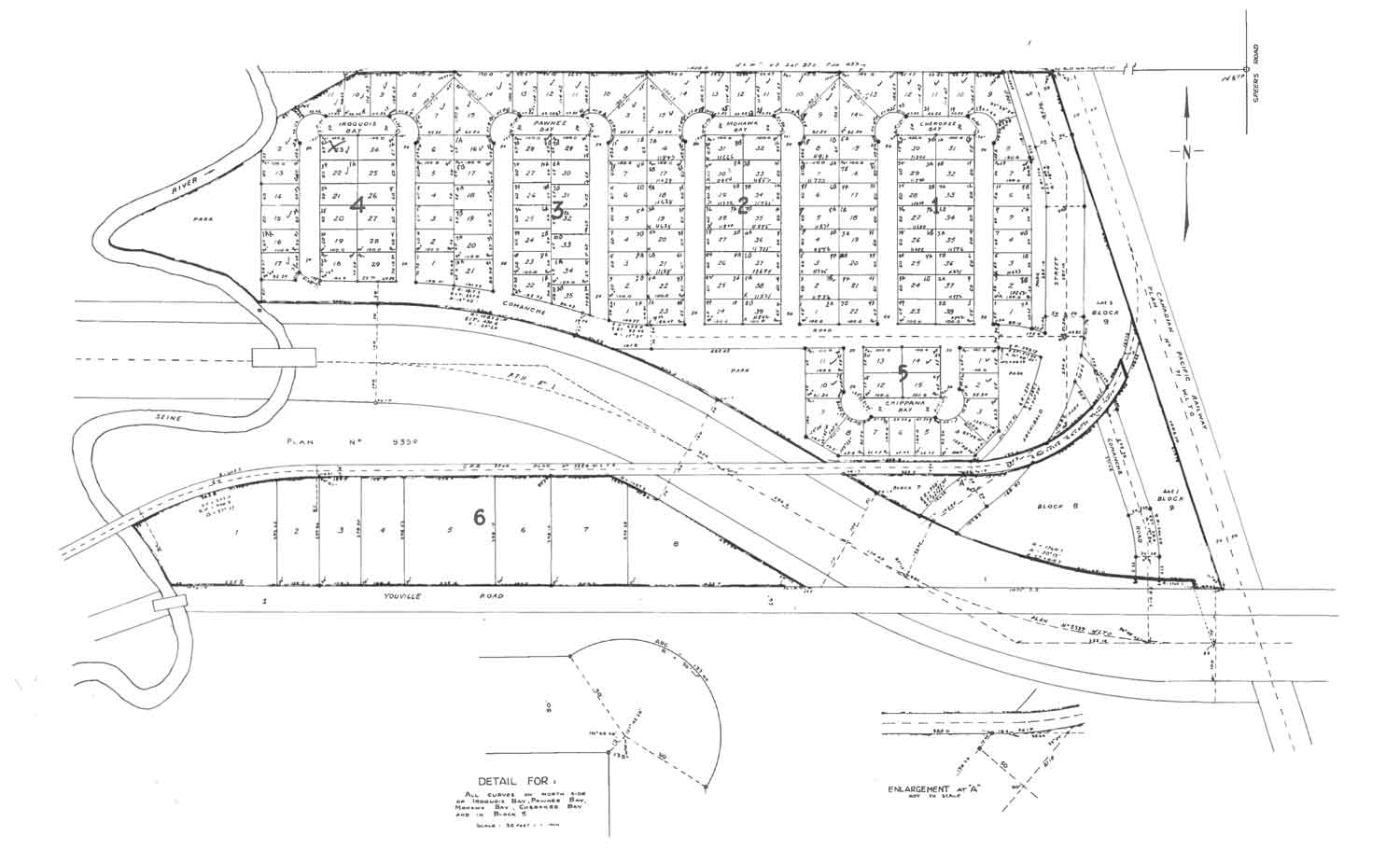

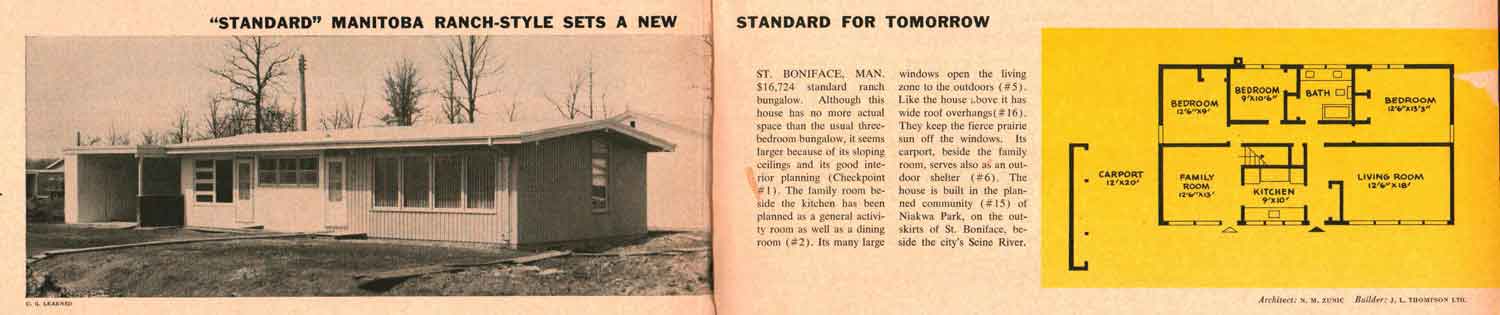

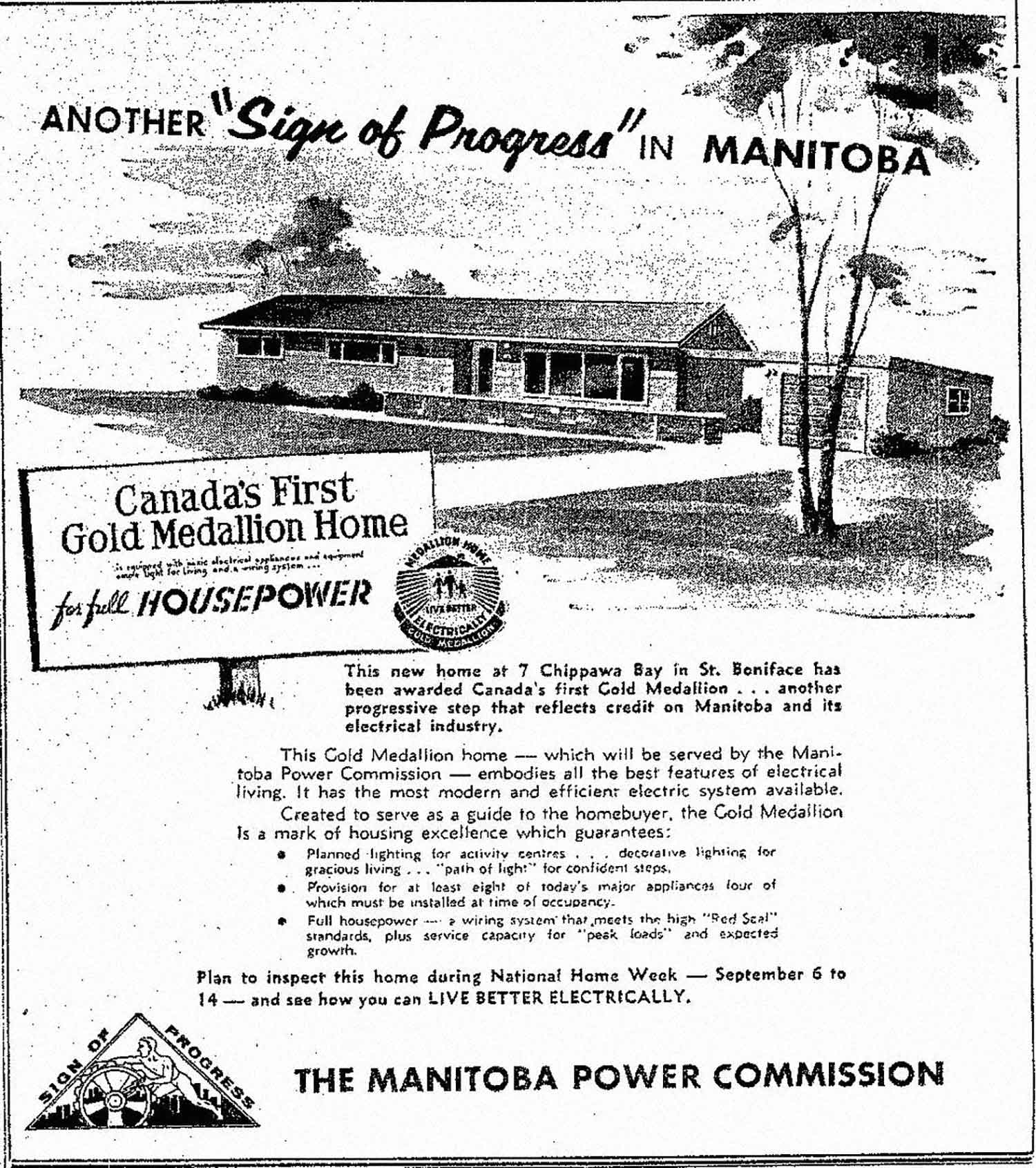

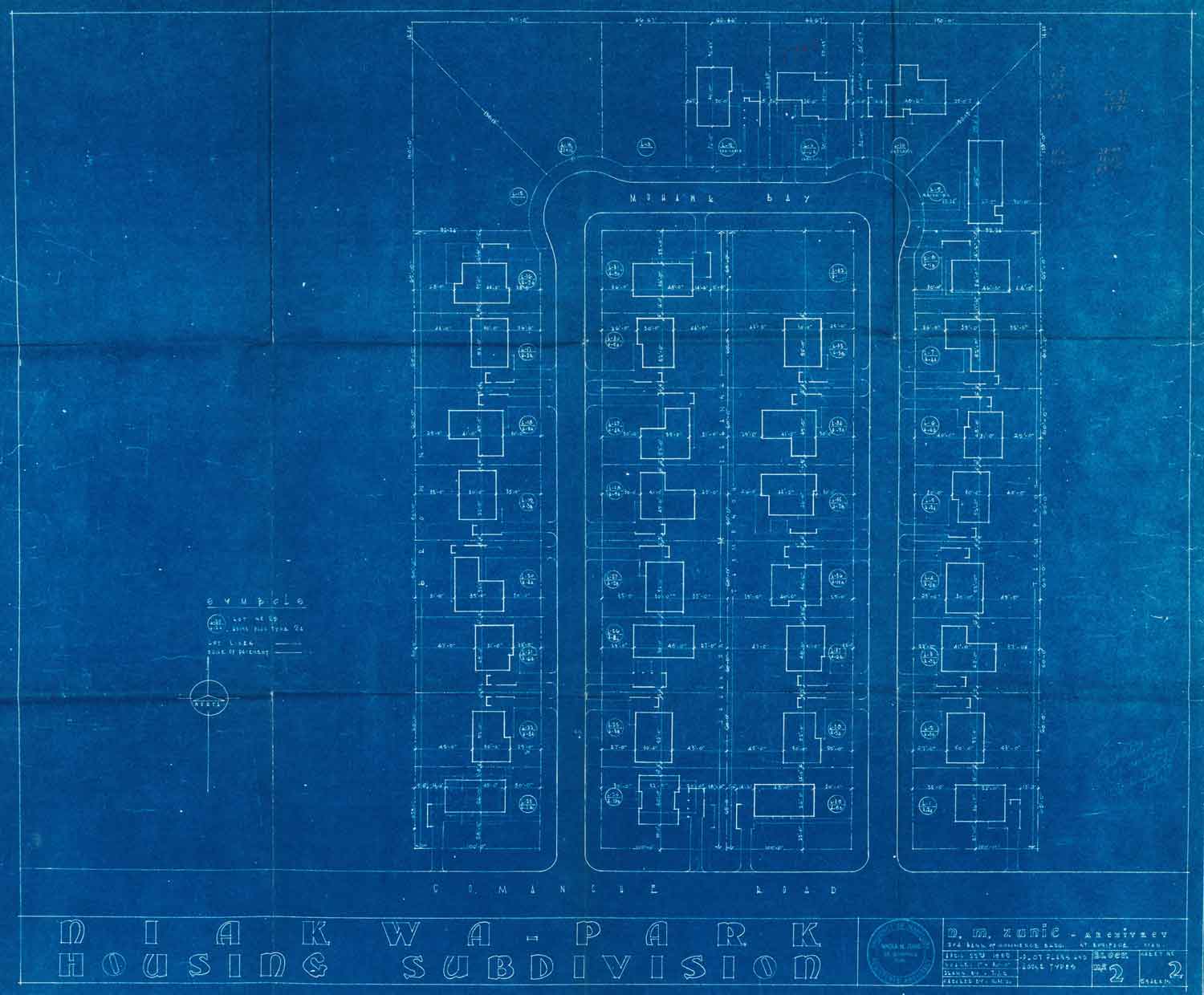

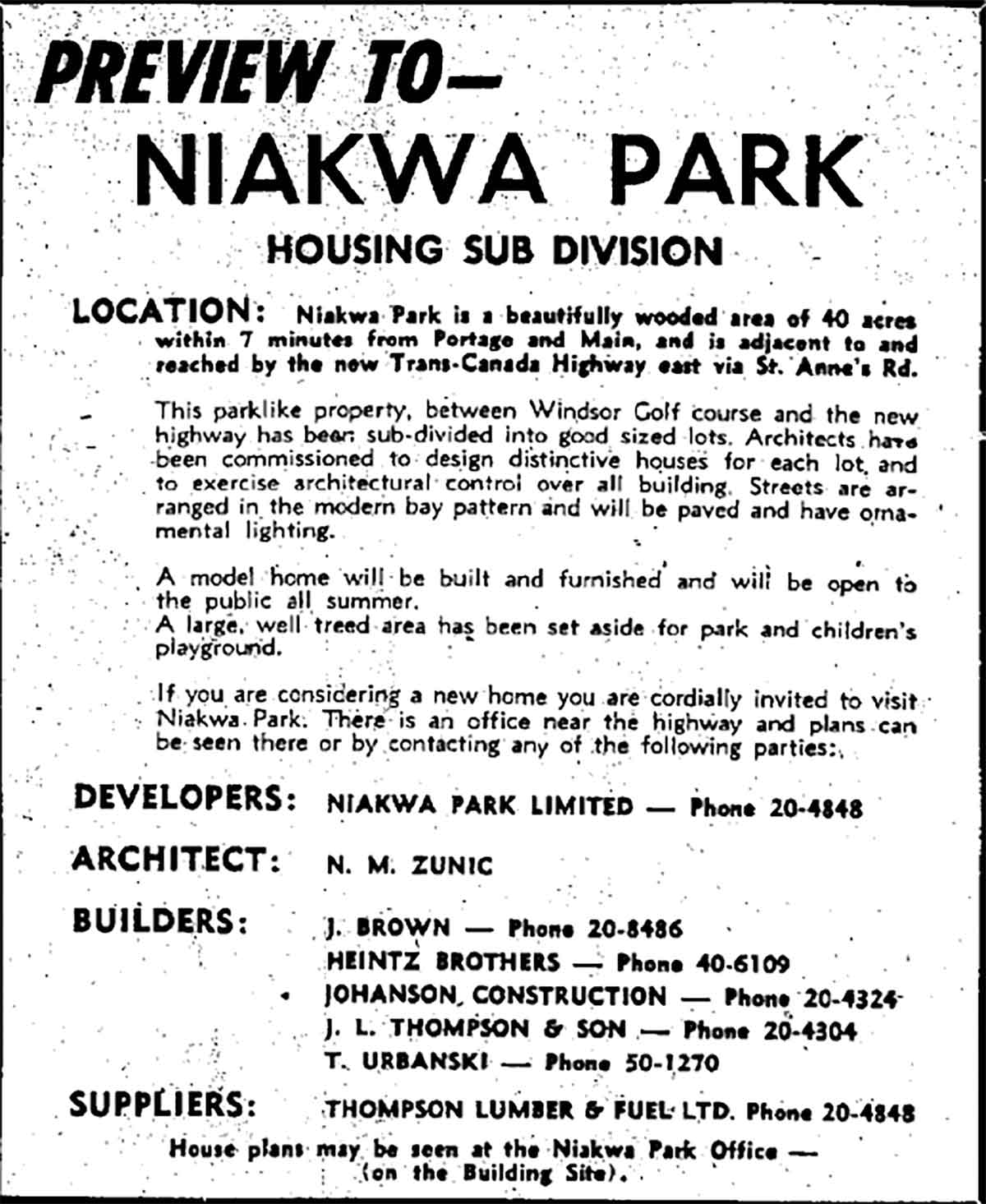

Niakwa Park, located north of Fermor Avenue, south of Windsor Park Golf Course, and adjacent to the Seine River, was developed in the mid‑1950s. When it was proposed, the project aimed to construct 160 homes on 16.2 acres of land. The area’s homes were designed by Nicola Zunic, a 1950 graduate of the University of Manitoba’s School of Architecture. The subdivision’s name is derived from an Indigenous term for “winding river,” and had earlier been applied to the Niakwa Country Club, established in 1921 and located south of Niakwa Park.

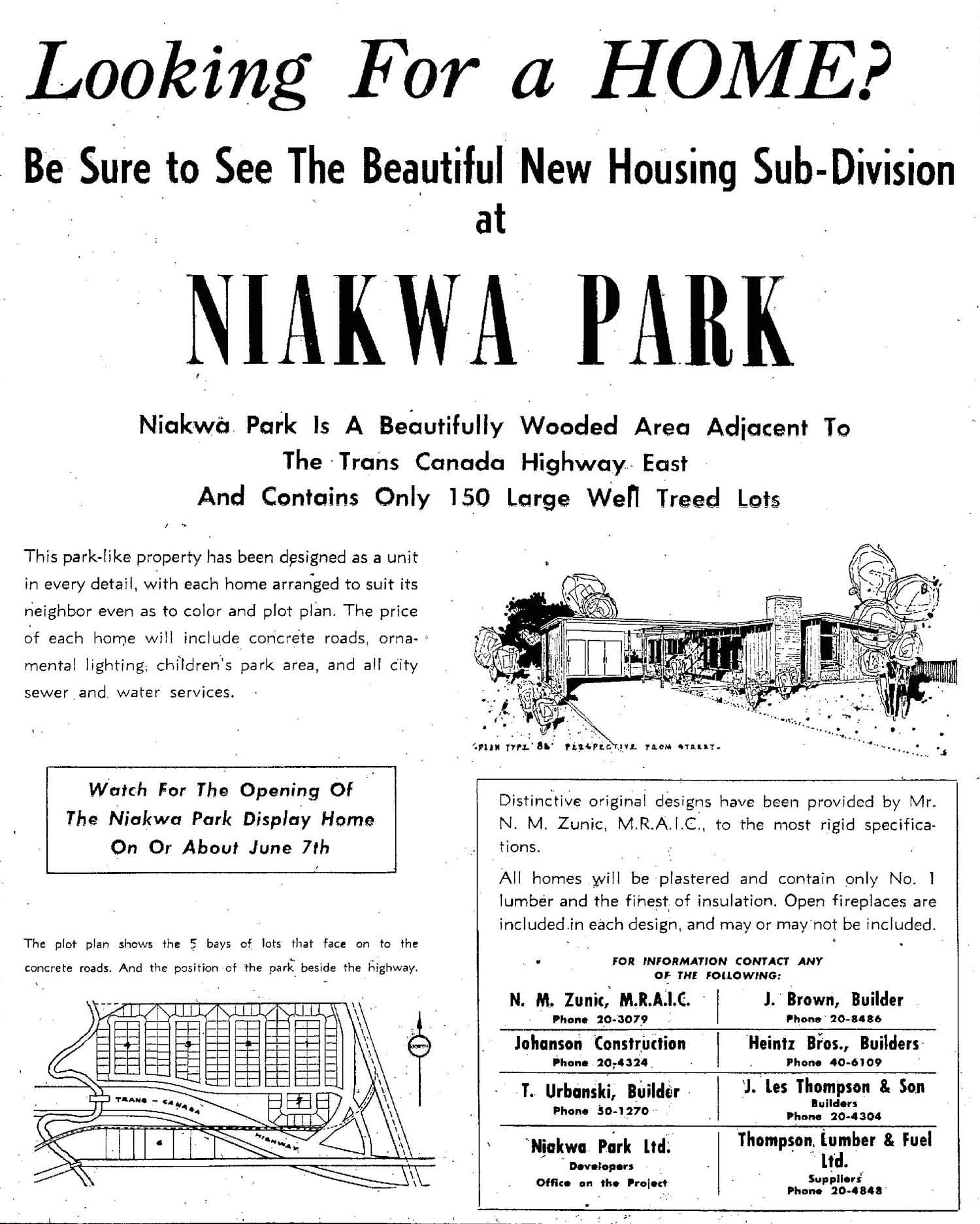

The construction of Niakwa Park was a direct result of a large population boom in St. Boniface during the post-war era. The number of people living in the municipality, which was amalgamated with the City of Winnipeg in 1971, increased by nearly 20,000 between 1951 and 1969. This growth rate significantly exceeded that of Metropolitan Winnipeg as a whole, resulting in an increase in housing development projects. One of these projects was Niakwa Park, approved by St. Boniface City Council in 1954. Niakwa Park Limited (then the Niakwa Park Syndicate) agreed to spend roughly $130,000 on roads and improvements including, as part of the agreement, constructing an extension of Archibald Street connecting it to the Trans-Canada Highway.

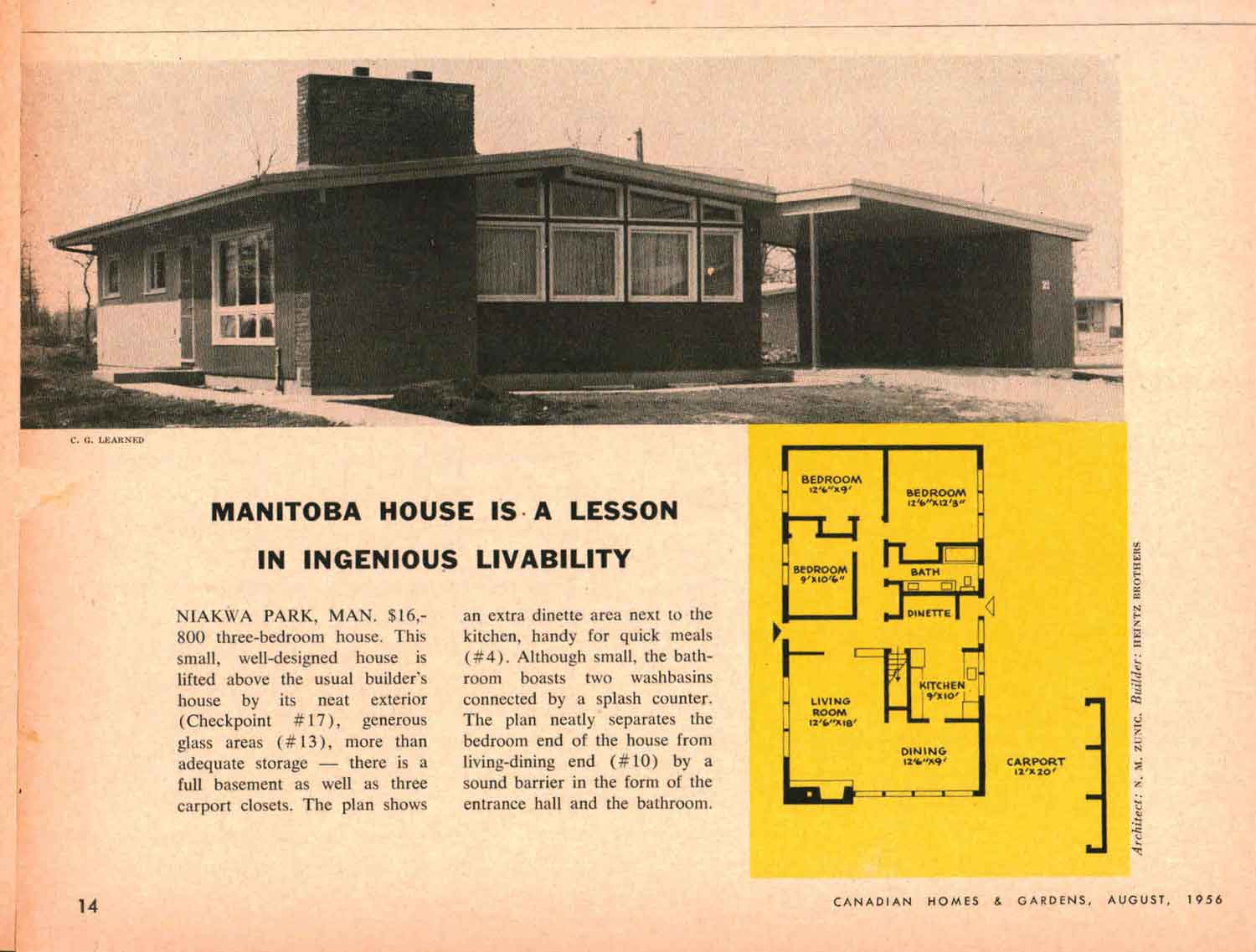

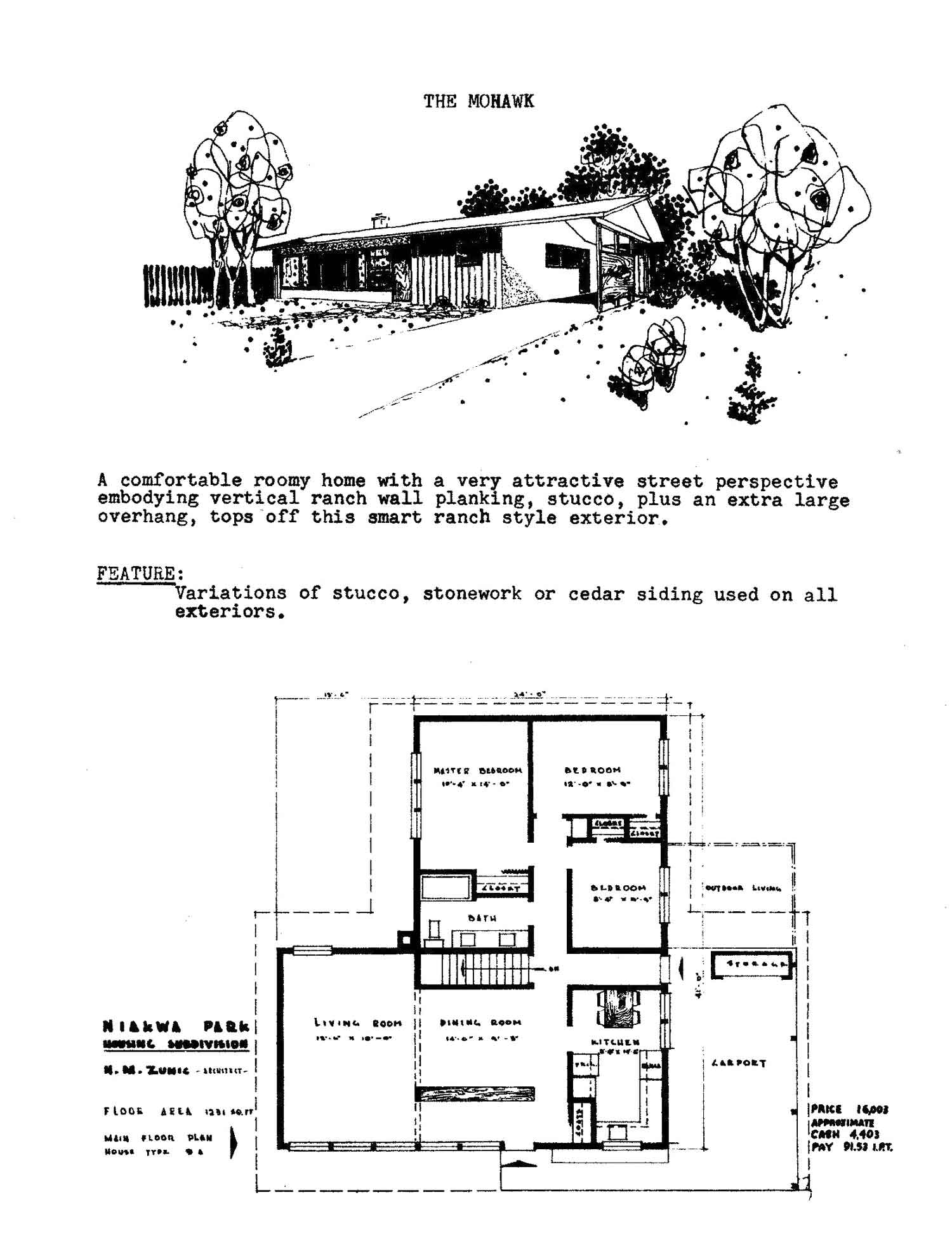

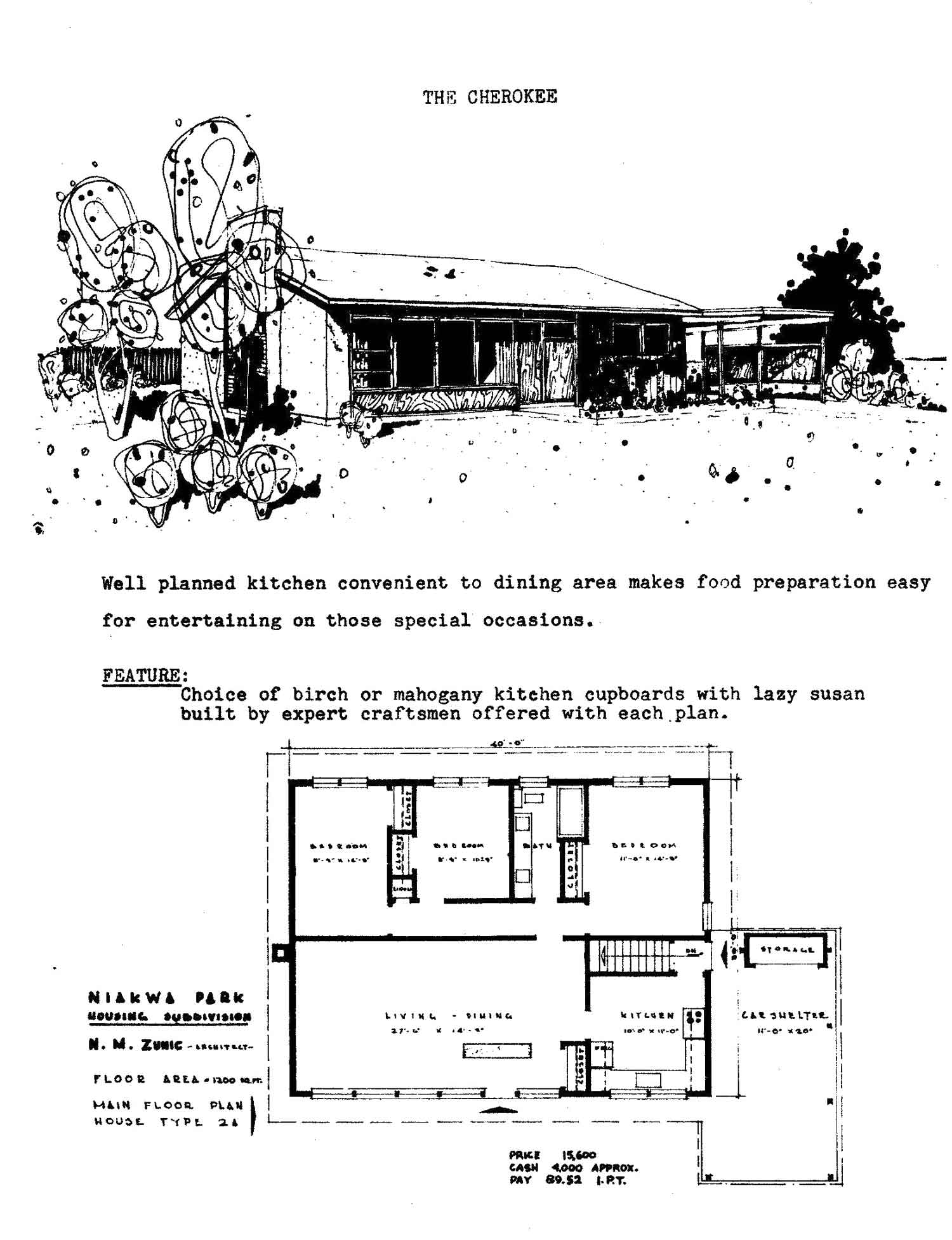

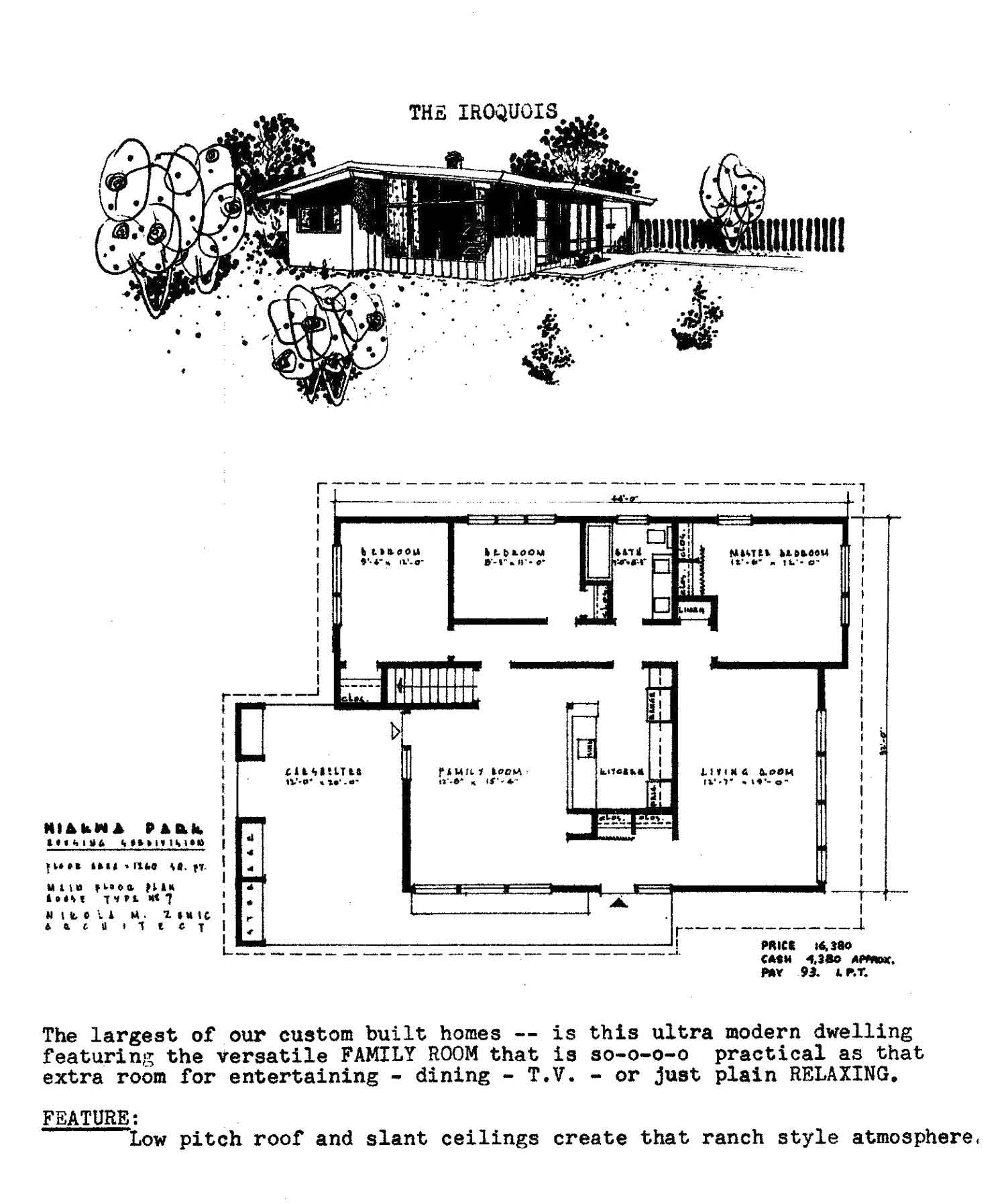

The subdivision was developed by Niakwa Park Limited. Beyond Zunic, partners in the area’s construction included: Johanson Construction; builders T. Urbanksi, J.Brown, and the Heintz Brothers; J. Les Thompson & Son; and, Thompson Lumber & Fuel Limited. Lorne Thompson, of the latter company, was an early leader in the area’s construction and orchestrated the purchase of the neighbourhood’s lots from the City of St. Boniface. The initial investment in the neighbourhood was $2.25 million, with homes selling for $13,000 to $15,000.

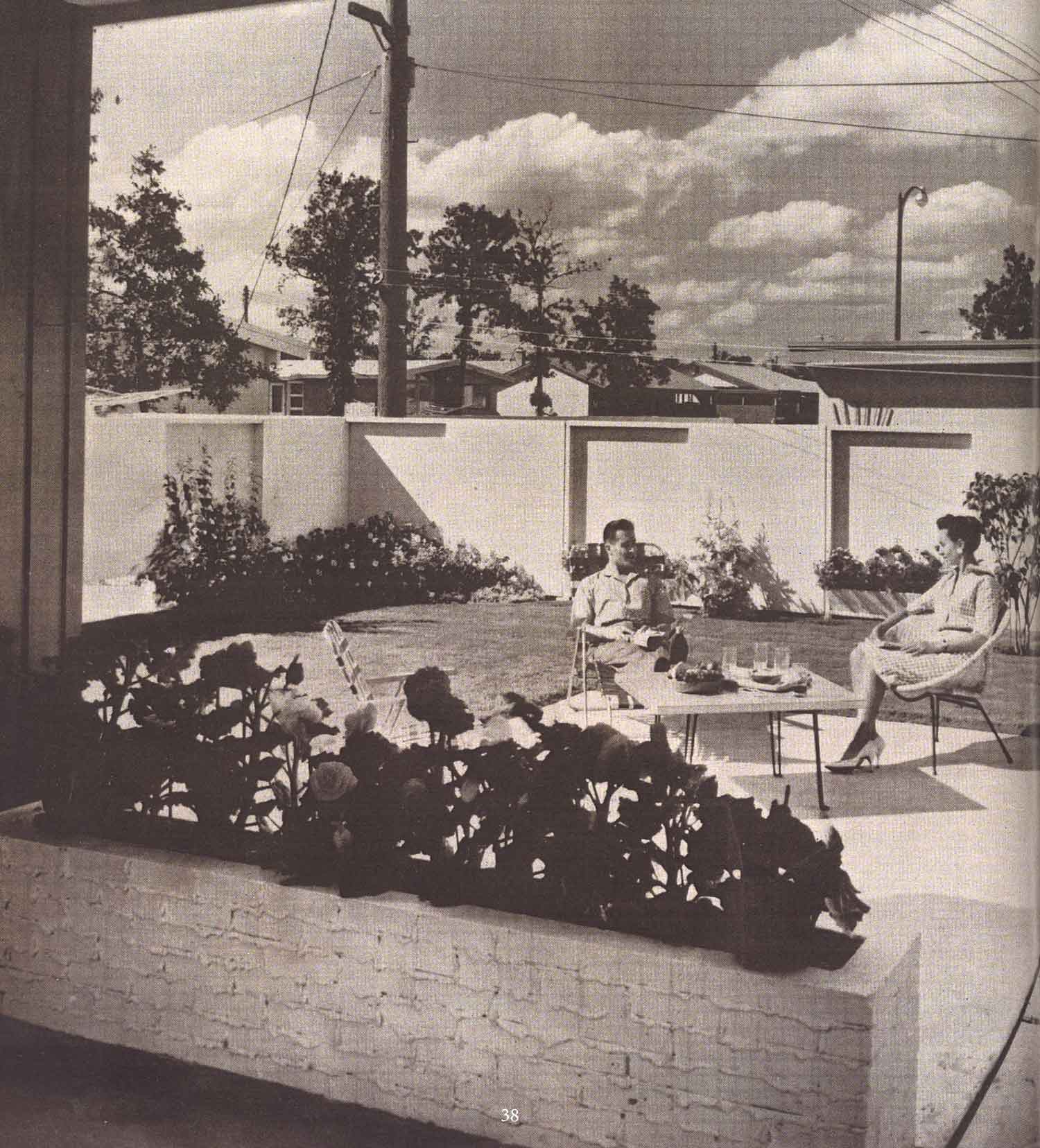

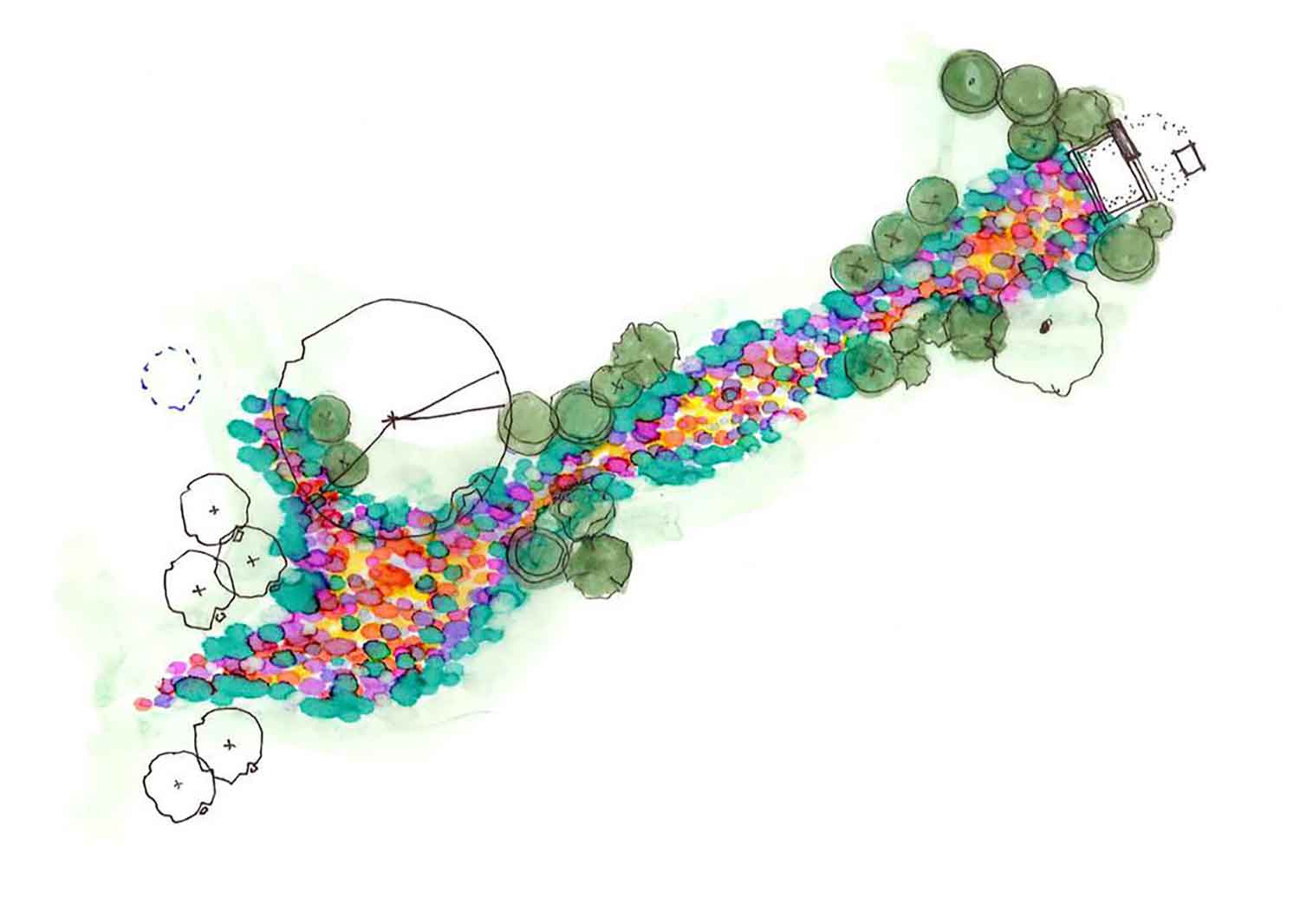

Of Niakwa Park, Zunic stated that he and his partners attempted to engender a certain diversity in design and wanted to embrace the park-like terrain, achieved partly by building around existing trees. Years later, Zunic commented further on the creative approach taken in the design: “…it was our plan that we wouldn’t set up the houses like soldiers.”