Introduction

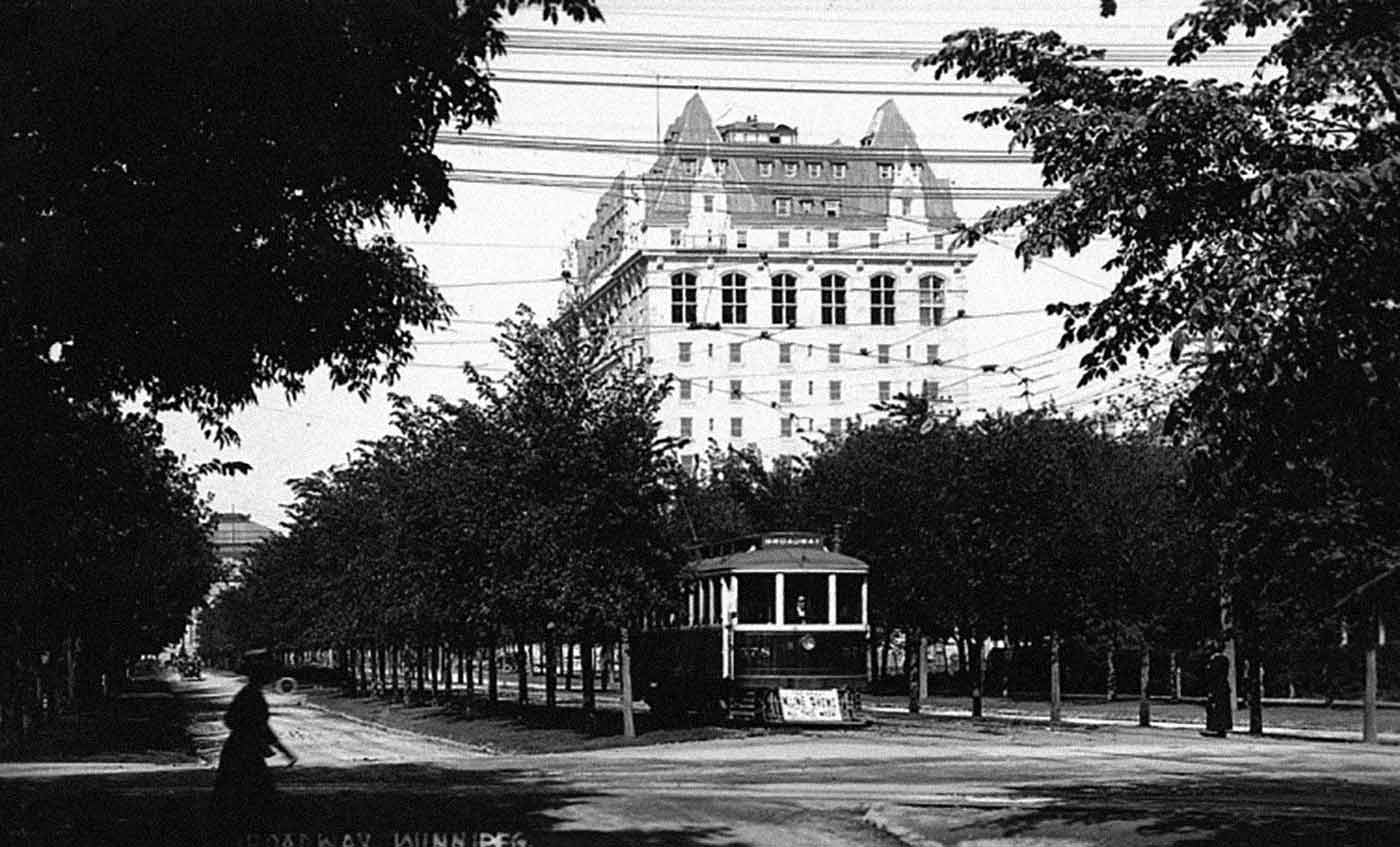

Broadway between Main Street and Osborne Street has long been an address of prestige, bookended by two dominant, significant works of architecture—Union Station to the east and the Manitoba Legislative Building to the west. The early history of the avenue was as a desirable residential neighborhood, with little commercial activity. A building boom in the late 1950s to early 1970s, however, was responsible for the development of the Broadway as we know it.

The avenue had for many years been home to the Bank of Montreal’s tennis club, the old Dominion Bank and a variety of residential apartment complexes, including the Tweedsmuir. While Broadway itself consisted of a mix of big homes, small enterprises, prestigious apartments and institutions such as St. John’s College, the area also functioned as a demarcation between commercial development to the north and a quiet residential enclave south to the Assiniboine River.

The boulevard was originally designed to have a formal, almost European look with a broad central median and with the aforementioned large civic points of interest on either end. The area was one of Winnipeg’s earliest and most exclusive residential districts, known as the Hudson’s Bay Reserve. The Government of Canada granted the large block of land near Upper Fort Garry to the Hudson’s Bay Company, after much of the surrounding territory became crown property. Cottages and other small structures appeared as early as 1873, and by the 1880s, many of the developing city’s wealthiest families had chosen to build their homes in the area. However, in the early twentieth century, as a number of areas around the city began to develop as alternative wealthy residential areas—Armstrong’s Point, Fort Rouge, Crescentwood, Wolseley and River Heights—many of Winnipeg’s elite families relocated to homes further from the city centre.

As in many cities, there was initially a large local opposition to the proposed development of apartment blocks in the area; however, dissent was quickly overcome and numerous luxurious multi-family complexes were constructed along Broadway. Many of the occupants were business people and government workers, from nearby establishments. While these luxurious apartment complexes remained popular during the early part of the twentieth century, the wealthy families of Winnipeg continued the move out of the immediate downtown area, causing a drastic demographic change. Over the following decades, many of the gracious homes in the downtown were subdivided into rooming houses, or torn down, paving the way for the development of the area as a predominantly commercial rather than residential district.

Among numerous forward thinking local developers, the locally based but British-funded development firm, Metropolitan Estate and Property Corporation (MEPC) was one of the earliest groups committed to making Broadway the “Wall Street of the West”, due to the perceived obsolescence of downtown Winnipeg office buildings in the late 1950s. Prominent corporations such as Investors Company, Monarch Life and Sovereign Life insurance companies paved the way for an increasing number of businesses to establish themselves on the Broadway.

This tour will focus on the post-1945 development of the area as a premier business district and a collection of modernist architecture designed by some of Winnipeg’s most notable firms.

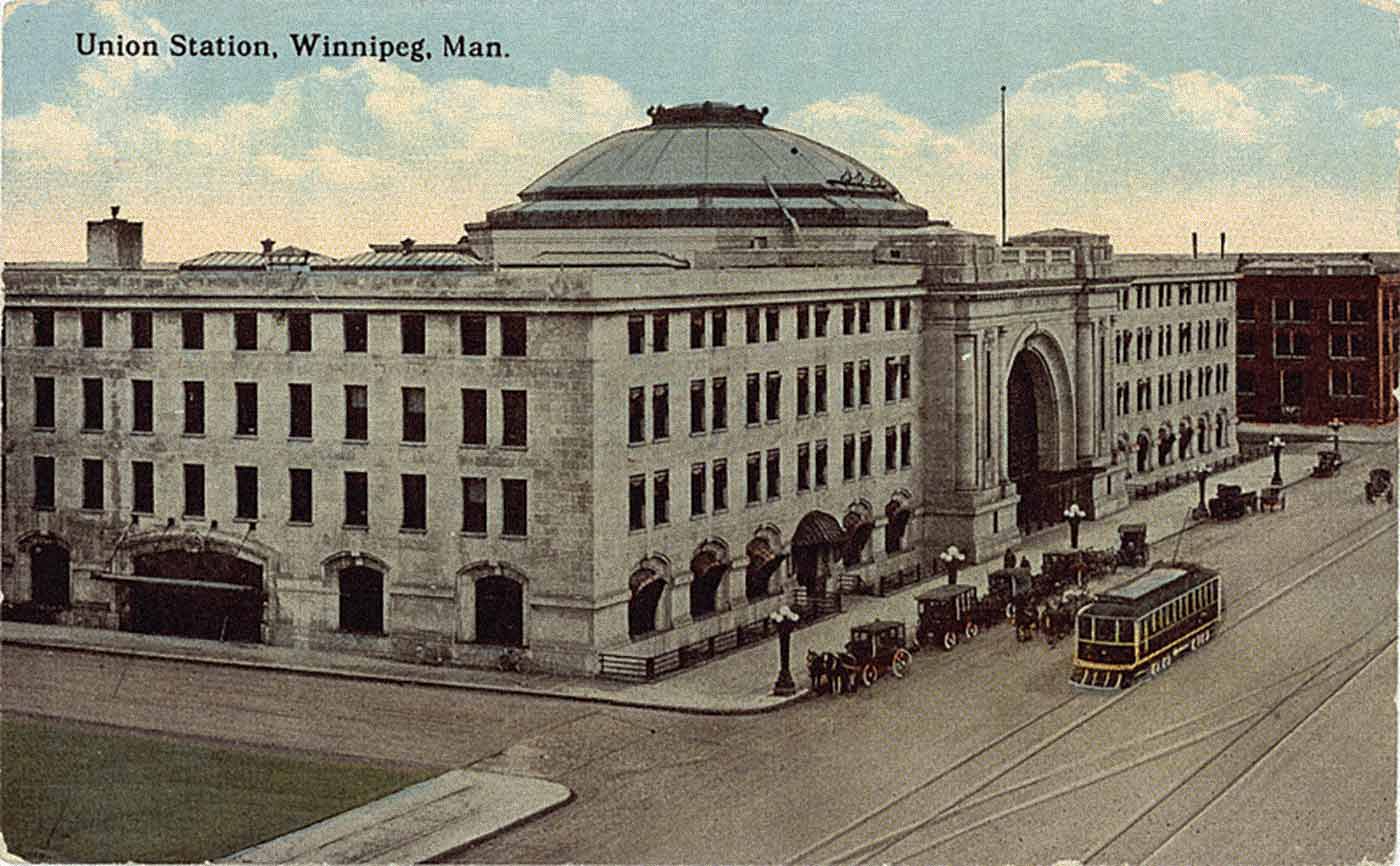

We suggest that you begin the tour at the east end of Broadway (at Main Street). Notice the variety of architectural styles in the structures of Union Station, the ruins at Upper Fort Garry, Manitoba Club and the Fort Garry Hotel. All of these structures provide an interesting stylistic contrast to the Modernist buildings discussed later in this tour.