Preface

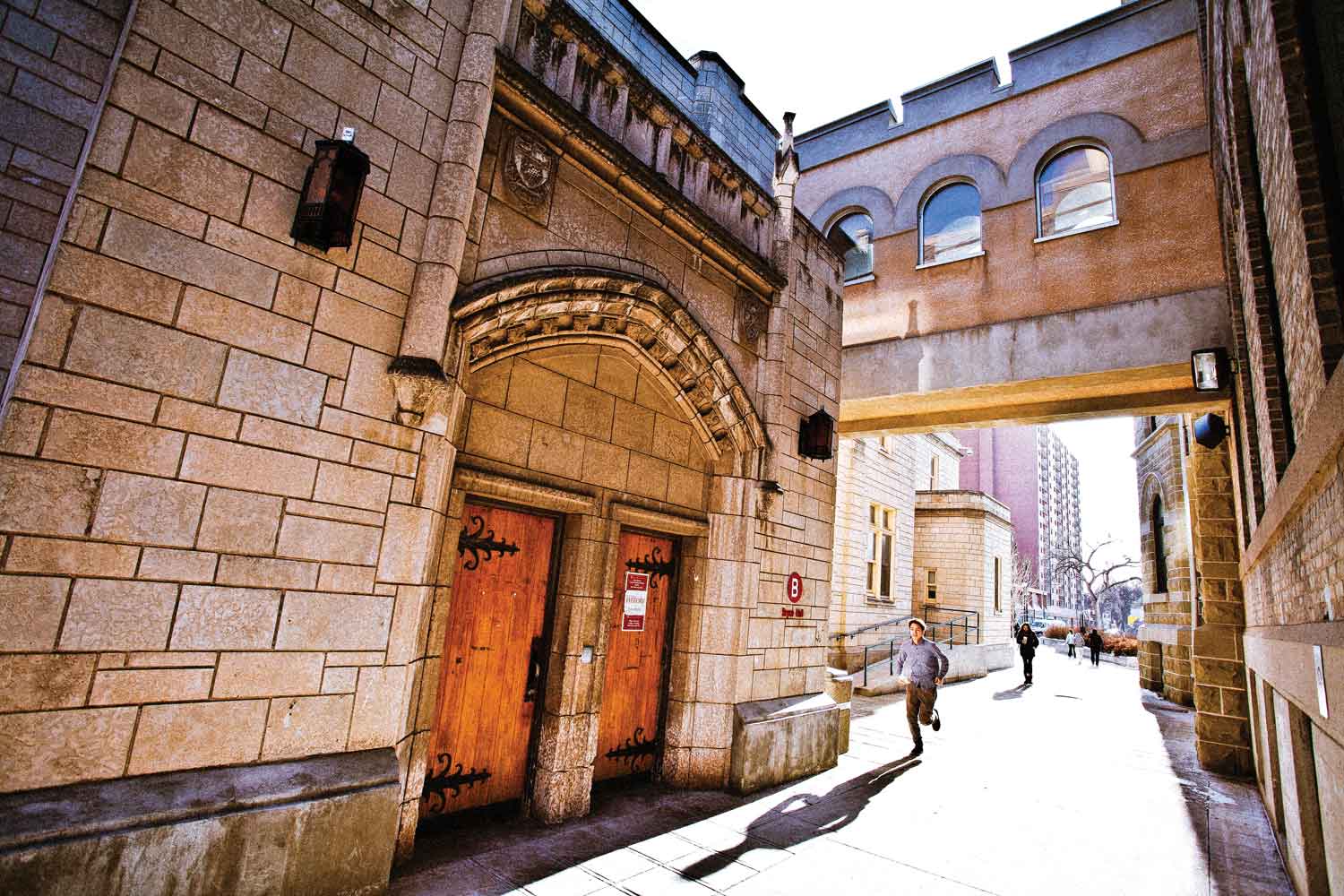

Winnipeg has had three building booms since the end of the nineteenth century and all three periods are well represented on the University of Winnipeg (UW) campus. Wesley Hall, built in 1894, epitomizes the Richardsonian Romanesque architectural style common to North American campuses during the nineteenth century. In 1938 Manitoba College and Wesley College joined forces to become United College, and the campus developed slowly through the twentieth century, with modest buildings surrounding a small grass quadrangle over a three-hectare site.

In the late 1950s, the administrators of United College made a momentous decision not to move to the suburbs with other colleges and join the University of Manitoba. Staying put in downtown Winnipeg lead to United College becoming an independent university in 1967, the University of Winnipeg, as well as enabling administration, faculty and students to engage with the urban core in a meaningful way. Though out the 1960s and ‘70s the university’s administration shed the model of a self-contained university and began to forge a new role in the city as a force for urban revitalization. As the influential Reid, Crowther report of 1967 stated, the UW is in a unique position to make use of down town Winnipeg, as if “the core is a living test tube.” (Reid, Crowther and Partners, “Interim report,” 1967)

In the twenty years after mid-century, much of the University’s internal and external reports emphasized the goal of supporting metropolitan Winnipeg, which was struggling as were other North American cities. Presidents W. Lockhart and H. Duckworth were bombarded with dire reports of Winnipeg’s decline. One solution being advocated in post-World War II North America by urban theorists was for universities to locate in downtown areas and actively pursue revitalization through physical expansion. Duckworth was quick to see the benefits of utilizing the resources, population and problems of the surrounding city, and immediately took down the fence that cordoned off the green space. He summed up this attitude in the slogan “the city is our campus.” (“President’s Address,” 1971) The physical expansion of the campus during the 1960s laid out one of the main strategies that UW has successfully used to contribute to Winnipeg’s downtown revitalization for over fifty years.

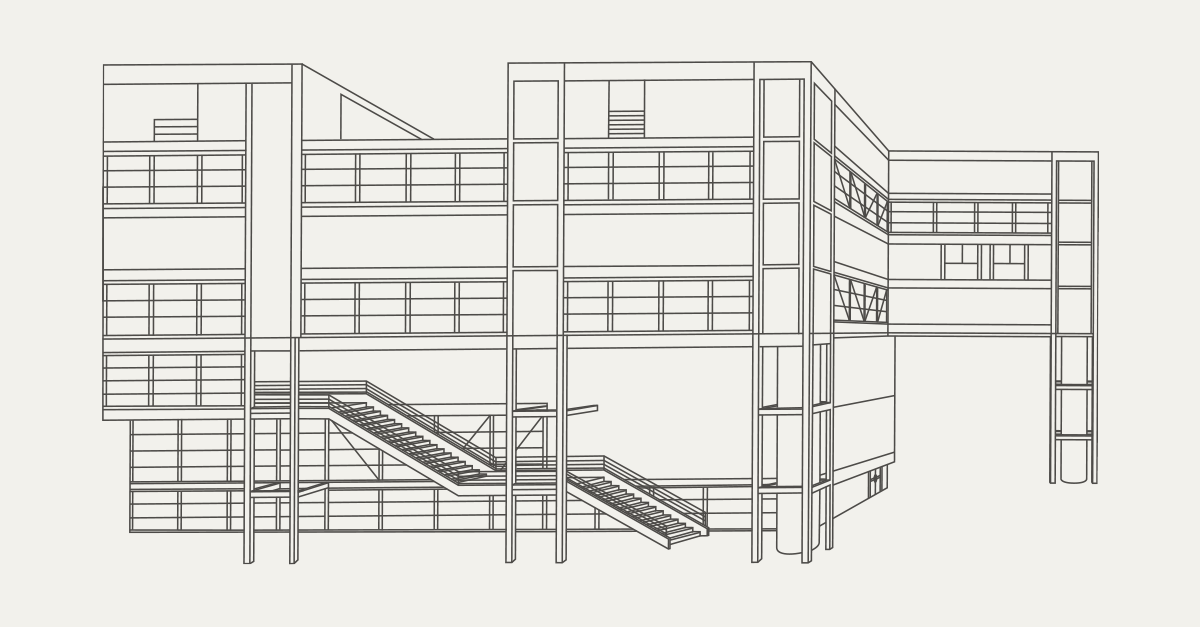

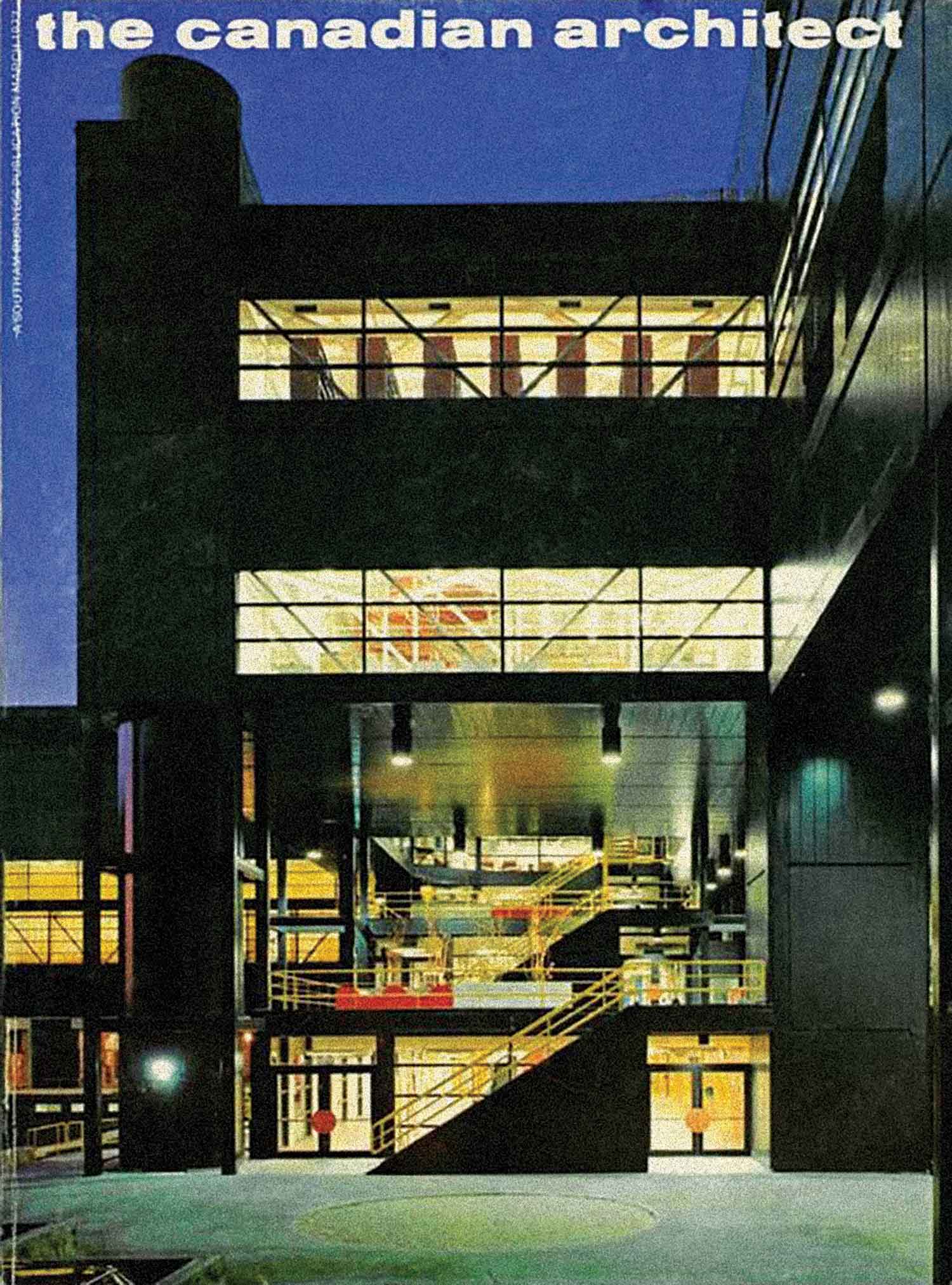

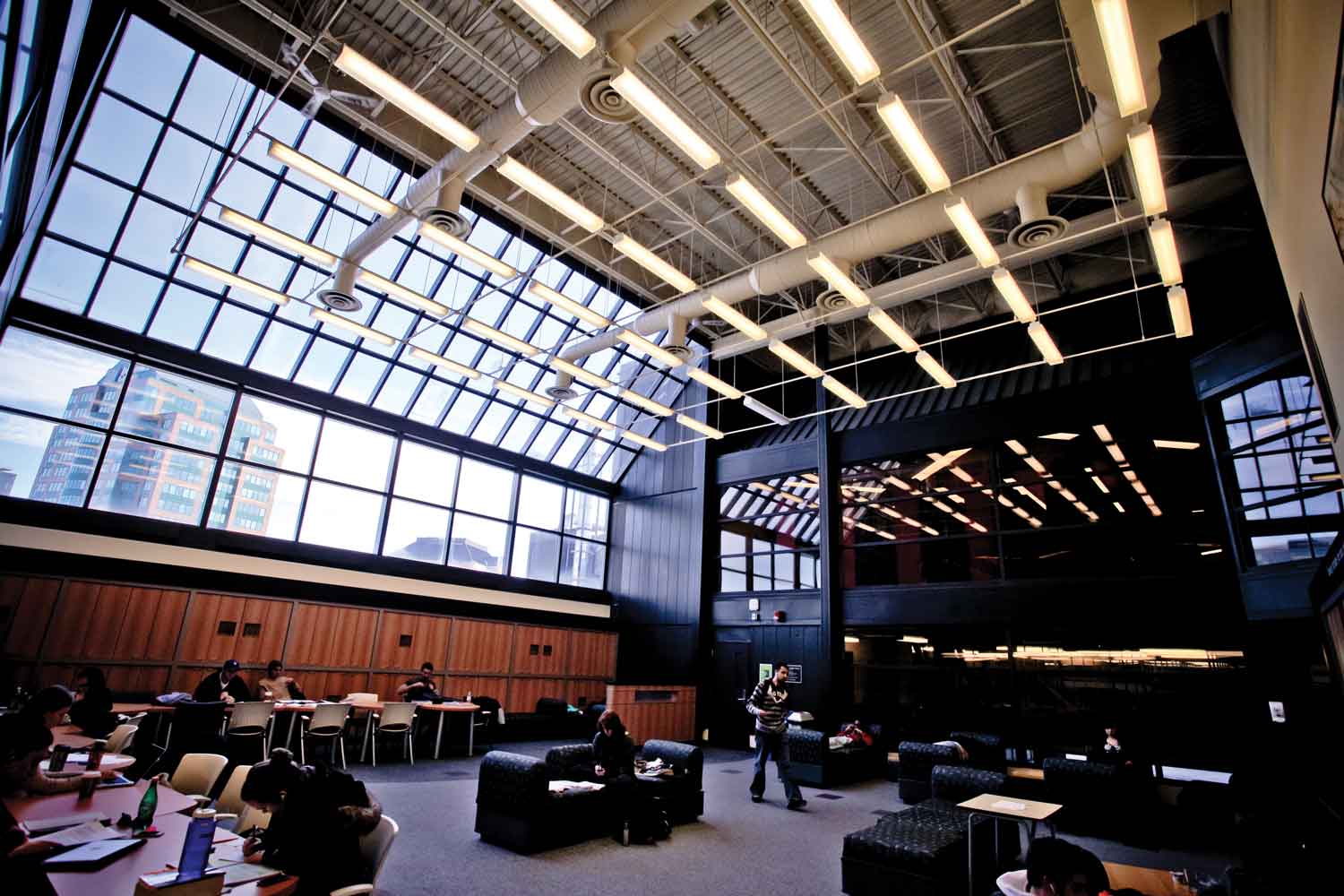

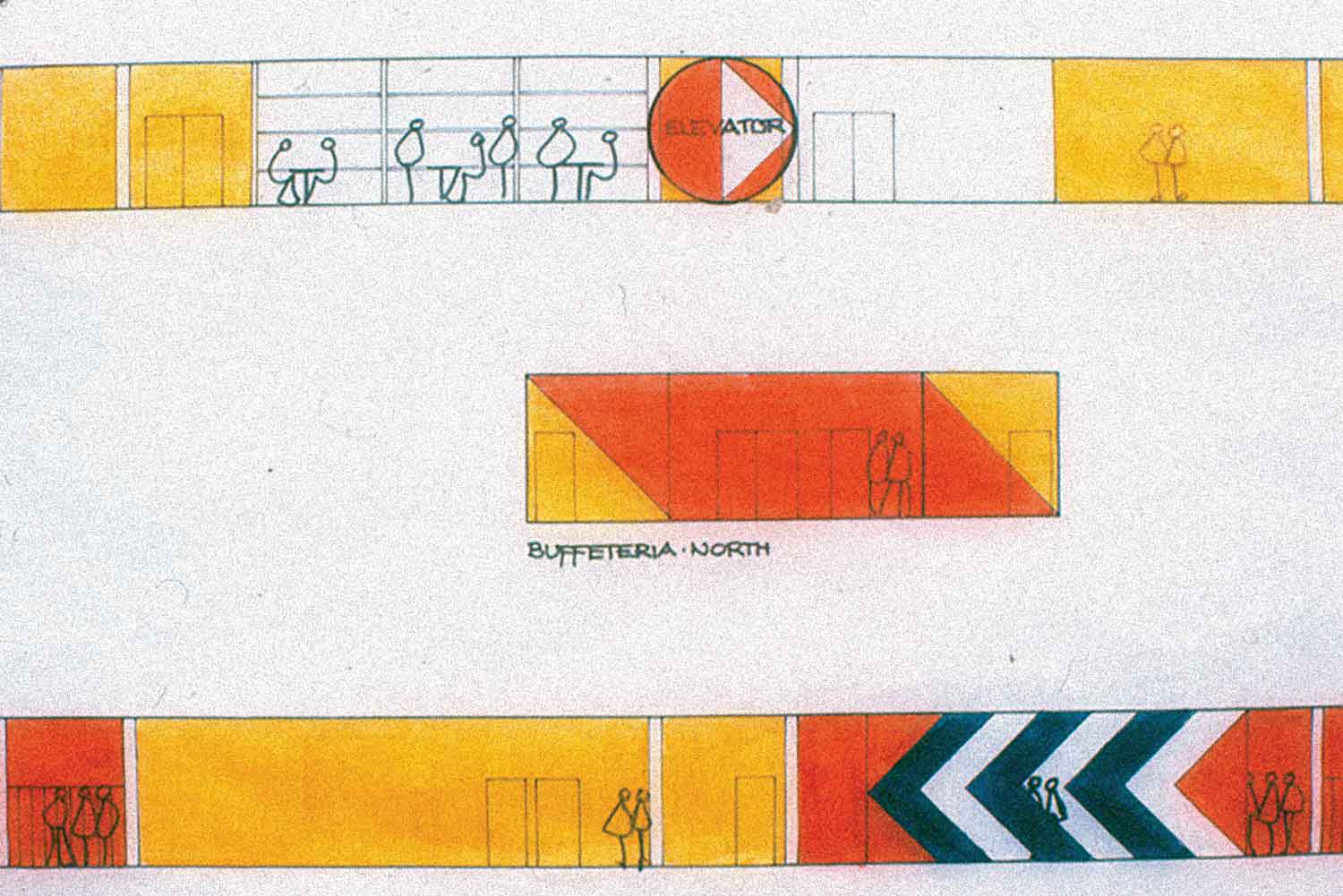

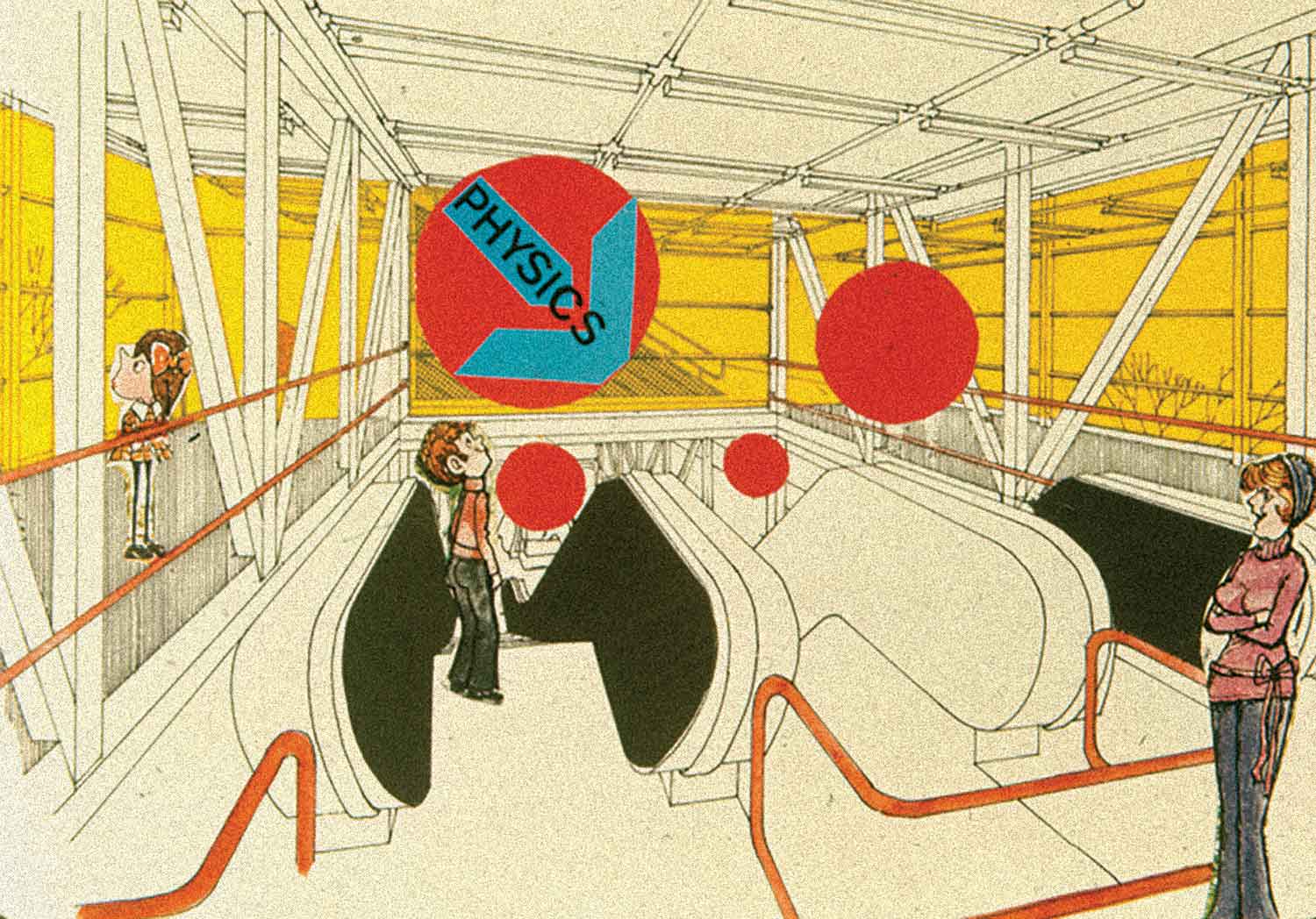

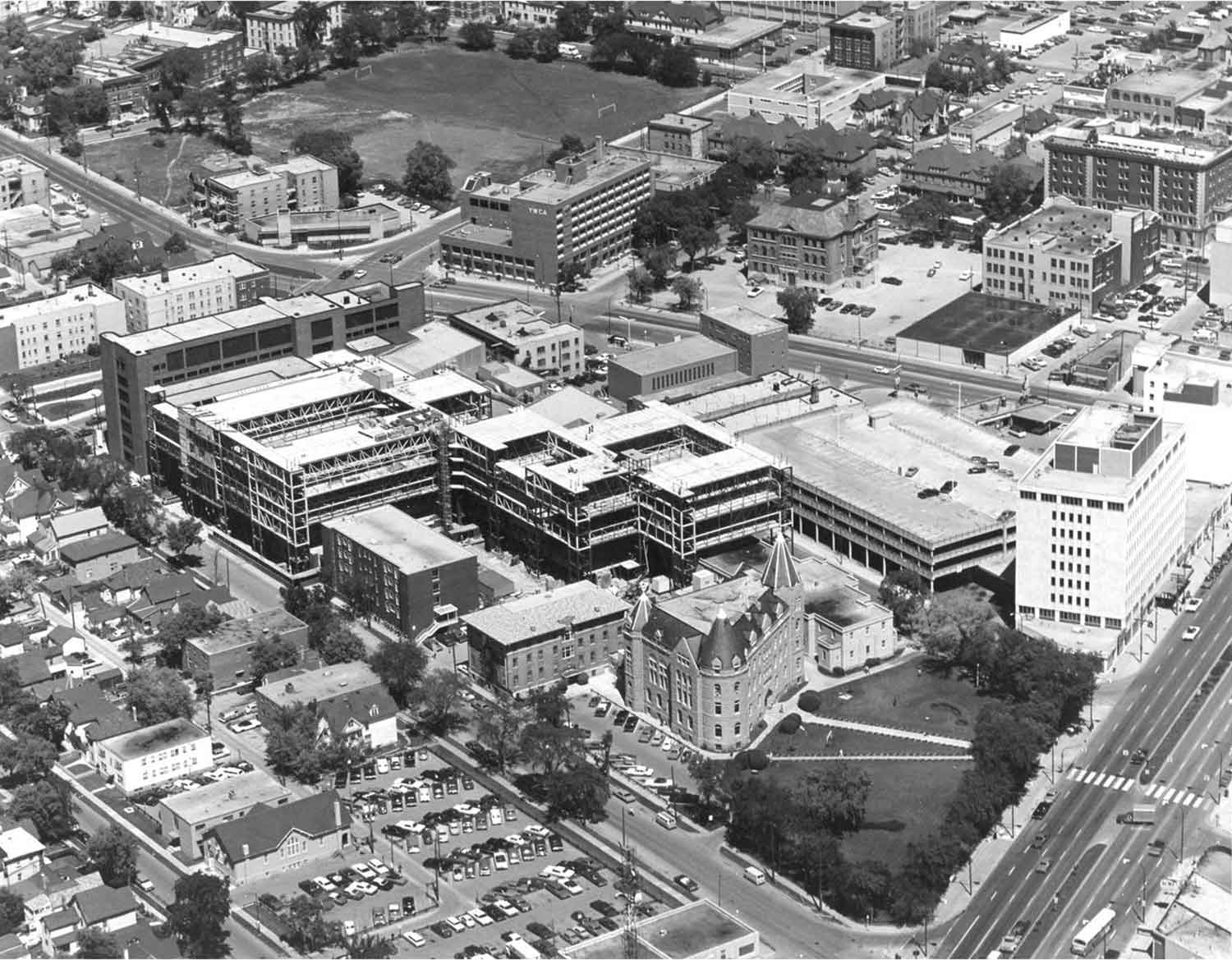

In response to United College’s new status as the University of Winnipeg , as well as to substantial enrollment increases in 1967 (31% in 1968), the administration began commissioning more sophisticated buildings, inaugurated with the refined brutalism of Lockhart Hall (1969). In 1972 Lewis Morse and Moody, Moore and Partners’ mega-structure, Centennial Hall, was designed to fill in the spaces between and above the older buildings, consciously breaking with traditional campus design. A “horizontal skyscraper,” Centennial Hall expanded the campus by eighty percent with a stylish building, whose very structure was a model of transparency and flexibility for educational practices. While Wesley Hall, with its crenelated towers, references the nineteenth century ideal of education, and Lockhart Hall attempted to modify the intimidating feel of Wesley Hall, through its use of the common materials of brick and concrete, Centennial Hall fully embraced the democratization of education embodied in Duckworth’s search for an “open university.”

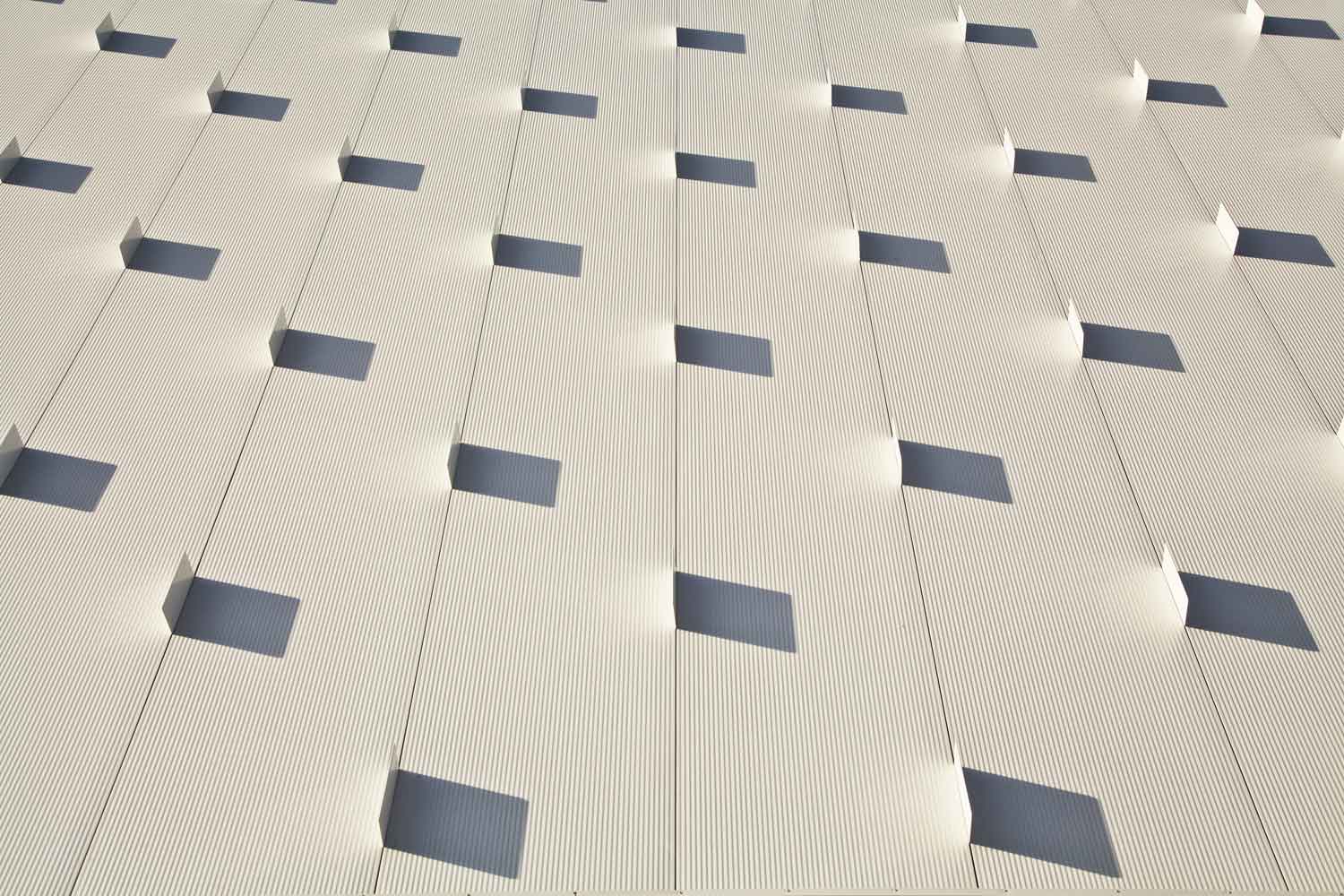

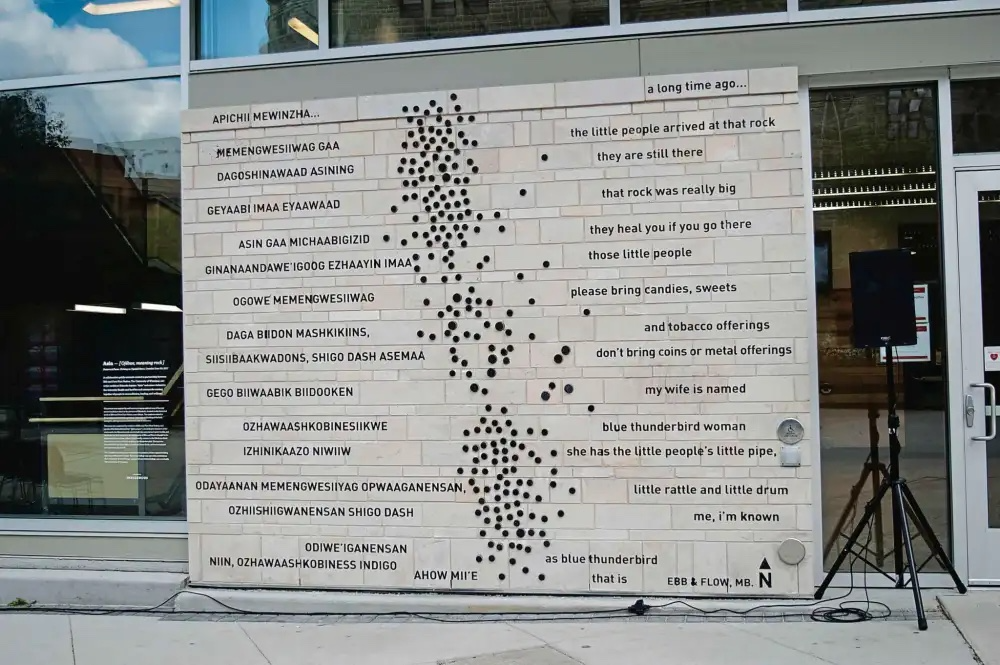

At the turn of this century, the conditions were right again for UW to act as an urban developer. The appointment of Lloyd Axworthy as President in 2004 is significant in this regard. Axworthy’s formative years were spent at UW during the 60s, as a student (BA 61), professor and founder of the Institute for Urban Studies (1969). He returned to Winnipeg to cap a career that had advocated for the well being of this city for over forty years. A second significant spike in student enrollment due to the echo generation’s coming of age, as well as greater access programs for indigenous and new Canadian students, engendered further expansion. Fears about Winnipeg’s core further declining, as the anchor stores abandoned UW's neighbour Portage Place Mall were also a factor in thinking about further development. This time campus expansion breached the original footprint of three-hectares, moving into adjacent under-utilized neighbourhood spaces. The creation of a non-profit organization, the University of Winnipeg Community Renewal Corporation in 2005, and the use of private and public resources to fund new buildings, resulted in a substantial expansion of the University’s footprint. The elegant Richardson College for the Environment and Science Complex (2011) added laboratories, McFeetors Hall (2009) accommodated student and family residences, and commercial and food services filled in the former Greyhound Bus Station, which had always been an unwelcoming space for students. The Duckworth Centre gym was expanded, and a new indoor stadium (Health and RecPlex) will soon offer indoor recreational space to the inner city population. UWinnipeg Commons, a residential tower located between the Buhler Centre and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, is being planned. Also important in terms of community relations were the additions of a basketball court to the front lawn, closing off Spence Street to traffic and a new daycare centre.

All this development within a short time frame has had its critics, and the impact on the local neighbourhood is still being assessed. The construction of the Buhler Centre at the gateway to Memorial Boulevard however, has certainly helped revitalize one of the most important intersections in Winnipeg, by framing the Manitoba Legislature building with an innovative neo-modern pavilion, even as the Hudson Bay threatens to abandon their flagship store. The intersection of Memorial and Portage has been labeled the “downtown arts precinct,” including the Winnipeg Art Gallery, which is undergoing an expansion for an Inuit Center to showcase their world- class collection, Plug-In Institute of Contemporary Art in the Buhler Centre, and the University of Winnipeg’s Gallery 1C03 and Anthropology Museum. It is not an exaggeration to see UW as one of the prime engines for the redevelopment of the western edge of downtown Winnipeg during the last decade. The decision made over fifty years ago by United College’s administration to stay downtown, boosted by the democratization of education in the post-war period, and innovative ideas about urban renewal have played a substantial role in helping to sustain Winnipeg’s core, and no doubt UW will continue to support the city well into the twenty-first century.

Dr. Serena Keshavjee,

Associate Professor of Art History, University of Winnipeg